FOUR WORKS BY ANATOLE SADERMAN TO REMEMBER AT PINTA BAPHOTO

Simple, yet with complex movement, the artist managed to capture what his sensitive eyes perceived, and today his name is part of the local art history as a reference in photographic portraiture.

Pinta BAphoto, the most important international photography fair in Latin America, honors Anatole Saderman (Russia, 1904 – Buenos Aires, 1993) in its 21st edition. Emigrating after the Russian Revolution, he studied art and philology in Berlin before settling in South America. In Montevideo, he met his mentor Nicolás Yarovoff and later opened his first studio, Foto Electra, in Asunción. In 1932, he permanently established himself in Buenos Aires, where he developed a long career as a portraitist of artists and intellectuals. He was a founding member of the Foto Club Argentino, the Foto Club Buenos Aires, and the Association of Professional Photographers.

His work was recognized by the Fondo Nacional de las Artes, which added 300 of his portraits to its collection, and he exhibited both in Argentina and in cities such as Rome, Barcelona, Valencia, and Singapore. He published Retratos y Autorretratos (1974) and received the Konex Diploma of Merit in photography. His legacy, centered on artistic portraiture, remains a cornerstone of 20th-century Argentine visual history.

Magnolia, c. 1935

-

Anatole Saderman. Magnolia, c. 1935. Impresión en plata sobre gelatina, 38 x 38 cm. Cortesía Bellas Artes

Magnolia (c. 1935) is part of the seventy photographs Saderman created for Ilse von Rentzell’s book Maravillas de nuestras plantas indígenas y algunas exóticas. According to the book’s prologue, its purpose was “to broaden our general knowledge of Argentine flora” through images “without tricks or retouching,” a novelty in local botanical literature, which had traditionally relied on scientific drawing.

The series was produced in his studio using artificial light and a neutral background to highlight forms and textures. In Magnolia, the chiaroscuro and highlights reveal both the softness of the petals and the fibrous texture of the leaves. As the curator Francisco Medail notes, by photographing plants “in the same way he photographed people,” Saderman transformed these images into “a declaration of modernity.”

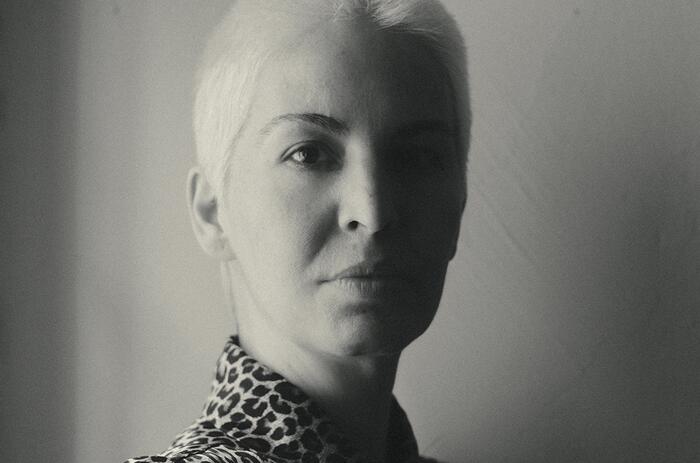

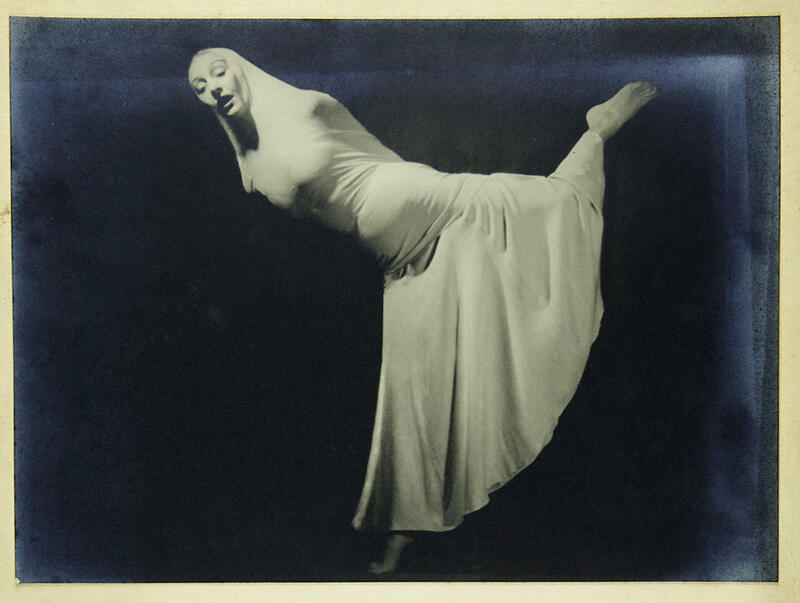

Biyina Klappenbach, c. 1938

-

Anatole Saderman. Biyina Klappenbach, c.1938. Gelatina de plata, 23,5 x 17 cm. Cortesía VASARI

Anatole Saderman was a central figure in modern photography. Together with Biyina Klappenbach, he formed a powerful creative duo in which performance played a fundamental role. Their sessions display playfulness, form, movement, and beauty.

“His interest escaped the most commercial demands of the genre; he moved away from pose and stereotypes, seeking something deeper,” explains Medail.

Enrique Wernike’s Desk, c. 1955

-

Anatole Saderman. La mesa de Enrique Wirnique, c. 1955

Anatole Saderman photographed hundreds of Argentine artists and intellectuals, including Spilimbergo, Urruchúa, Castagnino, Carlos Alonso, De La Vega, Berni, Borges, Neruda, Alejandra Pizarnik, Ernesto Sábato, María Elena Walsh, among many others. To capture Enrique Wernike, one photograph of his desk and a window as a light source was enough.

Carlos Alonso and Paloma, c. 1960

-

Anatole Saderman. Carlos Alonso y Paloma, c1960. Gelatina de plata, 45,5 x 34 cm. Colección Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes

“So distinctive was his style, yet so simple at the same time,” writes Medail. Carlos Alonso and Paloma is proof of that. It also confirms what Anatole Saderman claimed: “One cannot be indifferent to the subject; the craft requires losing fear, but one must never lose emotion. A portrait without emotion is not a portrait but a photo: a one-in-a-million photo,” according to Medail.

*Cover image: Anatole Saderman, “Biyina Klappenbach.” Courtesy of Galería Nora Fisch, Buenos Aires.