MATILDE MARÍN AND THE TRIMMINGS OF BEING A WITNESS ARTIST

Both the exhibited and the stored works draw attention in Matilde Marín’s studio. On the walls, her emblematic photographs steal the gaze, but so do the wrapped and labeled folders on her tables, the boxes full of books on the floor, and the stacks of files on her shelves. The image completes itself with her voice, the one that explains why the archive, too, is a protagonist.

It seemed she had been ready all along. She offered coffee and biscuits, elegantly arranged on a table for four, covered with a dark blue cloth patterned with white flowers. Everything matched the space—spacious, bright, cool, and orderly; a studio in San Telmo, next to the artist’s loft. “I might go off script; I have several things to contribute,” she said as she poured the coffee. Matilde Marín understood the process: there would be no need for retakes, explanations, or much intervention. She told her story before the small audience of three who listened.

The video recorded that morning would serve as an Open File, a short biographical film made for her participation in Pinta BAphoto, an art fair specializing in photography. It took time to find the right spot for the interview. The first choice was a small patio outside, where Ágatha, one of her two cats, played. The image was beautiful, but the noise from nearby construction made it unworkable. Tables, chairs, and armchairs were moved around in search of the perfect shot. Eventually, they settled inside the studio. Matilde sat on a large black chair—dressed in black herself, accented with violet boots—composed and calm. After a few clarifications, to which she nodded and smiled, she said, “Alright, whenever you’re ready.”

-

Fotografía del taller de Matilde Marín

Matilde sees herself as a witness artist. “I feel like a witness artist. I’m aware of what’s happening in the world, in society—I’m conscious. And my work, though it has aesthetic overtones, also carries a sense of social and political commitment. These are shown delicately, but for me, being a witness artist is a service that somehow fulfills my profession,” she said. Matilde records traces and leaves her own, and she feels at home in that role. She began her artistic career as a sculptor but grew passionate about printmaking, until an accident with her hands forced her to change disciplines. It was through photography, as critic Fabián Lebenglik once noted, that the world entered her work in a new way.

She rises to find names to cite—she doesn’t want to get them wrong. After speaking to the camera, she asks if what she said was okay. And yes, it was.

-

Matilde Marín. Faro de Hraunhafnartangi, Raufarhöfn, Islandia. (Localización: Lat. 66° 30' N Long. 16° 2' O). Fotografía analógica con intervención digital, 42 x 50 cm. Cortesía Matilde Marín

-

Matilde Marín. Campos de Hielo, 2004. Fotografía analógica. Sobrevuelo de glaciares ubicados en las Altas Cumbres de la provincia de Santa Cruz, en el límite geográfico entre Argentina y Chile. Cortesía de Matilde Marín

Matilde Marín photographed lighthouses around the world, along with their mystical, romantic, and political stories. She flew over rivers and glaciers, filming as she went. “Everything alive, everything natural, is an archive of intensity and immensity,” she confessed in one of those videos. Capturing the current state of nature—and imagining how it might look in the future—is also an artistic responsibility. Marín photographed Suspended Time during the COVID-19 pandemic: solitary images she paired with poems by Adriana Almada. She explored The Persistence of Art, photographing small, everyday moments in various cities where the word ART takes on multiple meanings. She materialized Illusion, immortalizing a day in the life of Karina, a bubble-seller; Need, framing carts filled with cardboard, garbage, and wood; and The Gathering, through photo-performances using paper, strings, branches, stones, packing tape, food, and soap bubbles as protagonists. She has no fear of creating images. “I can walk with my works,” she affirmed.

She speaks confidently, omitting no detail. Yet her confidence never overshadows her gentleness. “I’m somewhat adventurous,” she says, as Ágatha leaps over couches and tables, darting briefly across the camera’s frame.

She explained that she still remains faithful to her old love: paper. “Much of my photography is printed on cotton paper, in very small, carefully made editions. That’s where I do the mix. And this versatility has generated new situations, always welcome.” Now, her work is shifting toward photographic and documentary records, as well as written ones. “I want the artist who writes to walk.”

At a conference in Madrid, Matilde heard Robert Storr say that art cannot change the world, but it can leave a record, and she understood that the artist holds a certain kind of power. “In my publications, in a way, I leave a record—a small package to be looked at, to be read, and to remain in a library, for instance. It’s a form of transcendence,” she said. The image of her work as a small, transcendent archive-package is a captivating one.

To end the interview, she showed her works. “That’s the violet lighthouse in Australia, and this one is from Jules Verne—the Lighthouse at the End of the World. This one is from Iceland, the lighthouse closest to the Arctic Circle… This is Cape Verde, in the middle of the Atlantic… This one’s from Argentina; it’s about the fragility of that moment in 2001, 2002… I took that one in Venice in the ‘90s… That cup is from Vietnam… from Japan… from Berlin…” Her love for words shines through—in her fascination with Japanese literature, in her own photography books, in her search for stories, and now, in her new project: to let the artist who writes walk.

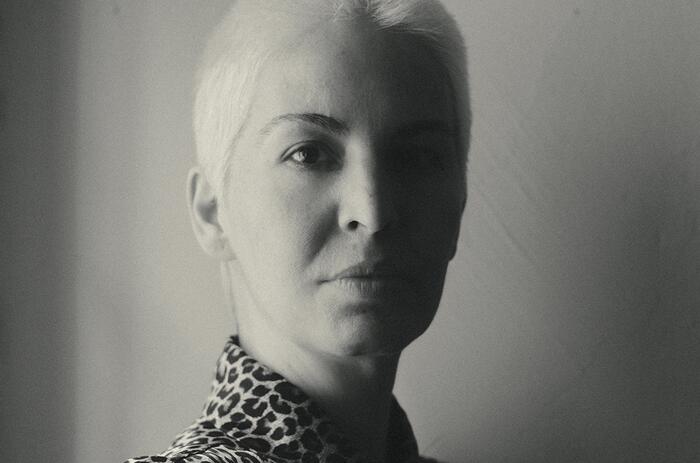

*Cover image: Portrait by Ariel Rivero.