FLORENCIA PORTOCARRERO: VISION AND APPROACH IN EMERGING ART

Florencia Portocarrero, curator of the NEXT section at Pinta PArC, opens a space for us on her agenda from Lima to talk about her curatorial work this year. He brings us closer to his vision and his way of approaching this task through sensitivity and openness to dialogue with galleries and their emerging artists. As the director of Bisagra, an independent art collective that she directs together with Miguel A. López, and the artists Andres Pereira Paz, Eliana Otta, Iosu Aramburu and Juan Diego Tobalina, she shares with us her desire to "horizontalize" relationships when thinking and to create an exhibition, an attitude that translates into the moment of curating NEXT.

What was the central thread that guided your work in Next this year at Pinta PArC?

I have covered Next since 2018, in consecutive editions with a break during the pandemic, and a pause last year in Miami. It is a section that focuses on emerging galleries and artists.

Understanding emerging in a simple context, in most Latin American countries, there is little institutional support, and in many cases, little state support. An artist can remain in a gallery or in the emerging category for a long time. I understand the emerging as a flexible category, especially for artists who have a constant, active, and dynamic presence in their scene but are still working to gain more visibility for their work. Emerging galleries are mainly those that bet on those artists, who are risky, as much more work is needed than when working with a consolidated artist.

But it is also the most common in Latin America, precisely because of the weakness of cultural institutions. I don't think it's the case in Argentina, Mexico, or Brazil, where cultural institutions may have a bit more history, but it is the case in most of the region's countries.

I realized that each gallery comes to a very different context, representing a very different scene. So aligning them with umbrella curatorial themes is a bit artificial. I think it is more interesting to adopt a methodology based on dialogue, which tries to respect the identity of the gallery and understand it as if it were a window to the scene where it is inscribed, the city. So we have dialogued with the galleries about which emerging artists they have wanted to show, either because of the moment they were in their career or because of the gallery's bet on the artist. It is a much more organic and biological process that does not consist of putting a theme to which they all have to align. It is a process of conversation with each space.

I think much of the work in those conversations with galleries and when choosing the artists who will participate has to do with how to take care of the public presentation, the work, of these younger artists. There is an intense and well-handled work with each of the spaces that allows knowing different scenes of Latin American cities.

And among the artists from the same gallery in the same country, do you see similarities in the way they approach their work? Between these three artists who were chosen within each gallery, is there a line that unites them?

Yes, totally.

They are tinged with the same cultural context.

Yes, totally. For example, the representation of Puro, with Maximiliano Siñani and Paola Bascón, is quite interesting. Both are Bolivian artists but live in Germany. Paola lives in Berlin, and Maximiliano lives in Frankfurt. And, for example, both are working around stones and rocks and the different ways of understanding their presence in the world, from their association with the divine within Latin American ancestral cultures, versus this nation that sees rocks simply as a resource. These tensions, for example, are very present in the stand, with Maximiliano from sculpture and Paola from drawing, painting, and also video.

Then, for example, in Constitución, they are all very idiosyncratic artists to the Argentine context, there is a surrealist vein that runs through the three works. A certain exploration of the sordid in the three artists.

But each stand is a world, each stand functions as a window both to the gallery and to the scene in which the gallery is part of. It allows the public to get in touch with the latest that is happening and also to respect the identity and the gallery, which is very important when one works with young galleries.

-

Florencia Portocarrero.

-

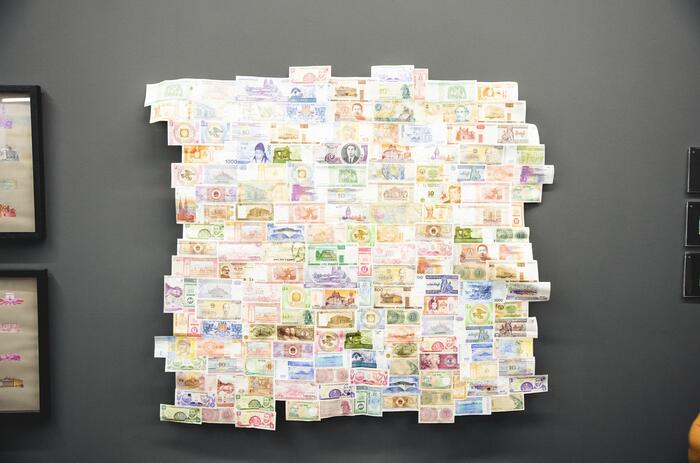

Clara Johnston. Período azul XII. Fotografía toma directa. 2022. 30x42cm. Remota galería.

-

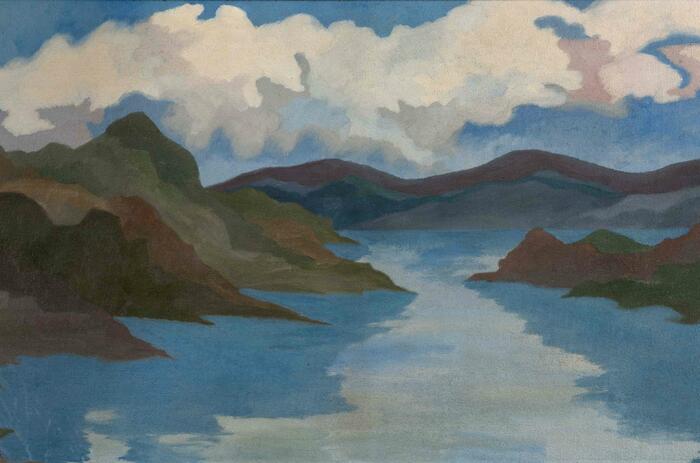

Carlos Cima. Sin título. Óleo sobre lienzo. 2018. 50x60cm. Constitución galería.

-

Isadora Villarino. Ausencias / Presencias. Dibujo en base a pigmento y lápiz sobre papel. 2023. 40x60cm. Espacio Andrea Brunson (EAB).

-

Colomba Fontaine. Sin título 2. Esmalte sintético sobre aluminio. 2022. 130x80cm. NAC galería.

-

Paola Bascón. Cuerpo-Montaña. Acrílico sobre tela. 2022. 70x55cm. Puro Galería.

-

Asuntos de salud pública (el derecho a morir en paz) II. Serie Asuntos de salud pública (el derecho a morir en paz). Tipos sobre papel algodón. 2021. 29.7x21cm. Vigil Gonzáles galería.

Did you have any special inspiration other than the years you had curated this section?

The idea is that we work for the galleries and for the artists, and not the other way around. So we have to enhance the distinctiveness of each space. They are sections to be curated in a sense of accompaniment and care, not thematically. It is another dimension of curatorial practice.

As for the galleries that participate in the NEXT section this year. What differential factor and richness does the fact of selecting galleries located outside the big cities bring?

Next is one of the few curated sections of the fair that is at the entrance of the fair. Almost the first thing the public sees is Next. Here it is felt that there is care in the way in which the work of these young artists is being presented. There is a work of curatorship understood as a work of care and accompaniment, so that the work is presented in the best possible conditions.

There is the Remota gallery, from Salta, directed by Gonzalo Elías y Guido Yannitto a very cosmopolitan and very international artist, who returned to Salta and decided to open a gallery to represent artists from Salta. It seemed super valuable to me and when I checked the gallery program it had some incredible artists. And also bringing some diversity. In Peru it is very common for indigenous artists to be represented by contemporary art galleries. However, I see that it is a slightly more novel proposal for a context like Argentina, which is a country that does not have such a large indigenous population. Remota represents Claudia Alarcón, wichi artist and absolutely incredible weaver. I realized that it had also won an award at ArteBA and it is a young gallery, very strong, fresh and what better way to invite them to participate in Next.

The same thing happens with Vigil Gonzáles, in Cuzco. At the time the pandemic was generated, the director opted to move to Cuzco and centralize the scene a bit. In Cuzco, the situation with the virus was much calmer than in the capital, which is much denser at the population level, and there was a certain amount of freedom. And from there, during those two years of the pandemic, he was able to energize the scene and decentralize it. I found it very interesting to invite him.

Another very interesting thing about Next is that it generates a sense of community. For many galleries it is their second or third time participating in the section. It is a small section of six galleries. The argentine gallery Piedras participated three times and in recent years it has established itself as a very important gallery, not only in the context of Buenos Aires, but also in the international context. This community of galleries is being generated that come to the section for up to the third time.

Three years of growing seeing how the rest grow and what new things arise between galleries.

Completely. Collaborations arise. Piedras and Vigil Gonzáles have collaborated several times. There have been articulations at the regional level thanks to the section between the galleries that have participated. That has been very interesting, especially from Lima, which is not necessarily a center for contemporary art. But, nevertheless, it is a city of ten million people, an important city with a tradition of collecting that, for example, does not exist in other Latin American capitals. It is a small but equally interesting market and one that many galleries from other parts of Latin America are interested in exploring.

-

Matías de la Guerra. Intimidad Inmóvil II. Serie Intimidad Inmóvil. Cerámica esmaltada y alto impacto. 2023. 15x18x4cm. Remota galería.

-

Catalina Oz. La fuente de las aguas luminosas. Cerámica esmaltada, pintura china y resina UV. 2021. 23x15x12cm. Constitución galería.

-

Mercedes Perez San Martin. Paisaje 03. Óleo sobre tela y barniz de cera. 2022. 70x115cm. Espacio Andrea Brunson (EAB).

-

David Scognamiglio. RF 3. Serie resistente fragilidad. Escultura de bronce y luz. 2022. 60x40cm. NAC galería.

-

Maximiliano Siñani. Apacheta n9. Video. 2022. Puro Galería.

-

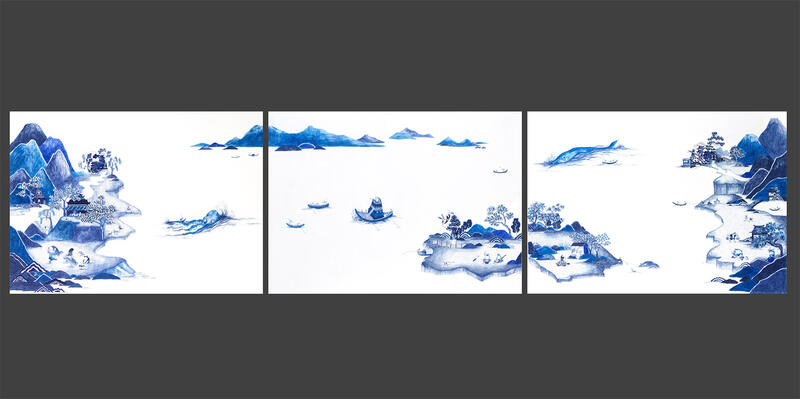

María Ossandón. Yokai. Tríptico. Cerámicas, dibujo a tinta y lápices polychrome sobre papel de algodón. 640 gramos, libre de ácido. Enmarcados con aluminio blanco y vidrio museo. 2022. 57x228cm. Aninat Galería.

The emerging galleries and more contemporary artists also bring a lot of indigenous art, right? Is it normal for emerging galleries to stage indigenous art?

Yes, in Peru it has been happening for a long time because the debate around Amazonian art comes first, which is a super important issue in Peru, the Amazon is a very rich territory. There are some incredible artists, an impressive visual culture. For several years now it has been very common for indigenous artists to be inserted as important artists within the local art scene. Chonon Bensho for example, is an Amazonian artist from the Shipibo-Konibo community who has won awards in the cultural scene. I think that it is a situation a bit advanced in relation to other countries where the presence of indigenous communities may not be the majority.

Indigenous art brings a lot of tradition and history from years ago. It is interesting that it is installed today as emerging art. That double face is spectacular, between history and today.

It has to do with the fact that the majority of indigenous artists, who are part of the contemporary art circuit, are young artists. They are contemporary to other emerging artists. They have had access -perhaps unlike their parents or grandparents- to a formal education, to the university and they can compare this training in Fine Arts with their own traditional training and super interesting things come out of these mixtures.

The work of co-participation and co-responsibility that Bisagra proposes for the exhibition Cuerpo Multiplicado is very interesting, where Bisagra steps aside and hands over the decision-making process to this chain of women who build the path of the exhibition. What was the motivation behind generating this chain, this sharing system?

Bisagra began as an independent art space that we opened in 2014 with some friends and collegues, who is also one of the fair's curators. We are two curators and four artists. We are now a collective rather than an independent space, which is activated according to different projects.

“Multiplied body” was an alternative to that moment in which art could not be seen directly. And we have applied the usual methodology, we have played with what it means to be a collective, an artistic institution, and try to horizontalize relationships. To think that, above all, we work for the scene and for the artists, and that the artists know their work more than anyone else. So, the idea was that we get together with a first artist and see what would happen if that artist invited another. It was like a kind of chain according to the associations they found between their own work and the artists they invited.

Much of the experience proposed by Bisagra has to do with co-creation and co-responsibility. Like a contamination between practices, a horizontalization of those of the different hierarchies at work or of culture.

About the importance of the feminist perspective in art. Do you feel a commitment to install a model that gives more prominence to women in the art scene? What role would be important for women to play in art today?

I feel that lately there is a lot of movement, a lot of awareness on the part of women artists and cultural workers that there is a history of erasure that precedes us. And that it is important to act in the present to somehow counter that history. I feel that we are at a moment where feminist ethics has slipped a certain common sense into what is understood as an artistic, ethical, committed and interesting practice.

Certain hyper masculine gestures, which were perhaps successful before, are now possibly a little more questioned. I think it's even a difficult time to be an artist, a man, white and straight, and that many male artists or artists with that hyper masculine sensibility right now don't find a place because a lot of the issues that are being discussed have to do with feminist ethics. , ethics of care, commitment to nature, environmental issues, sometimes indigenous.

I feel that a lot is being done from the present. However, not necessarily from the research. It's crazy, because many things can happen, there can be many exhibitions that expose these women, but if that doesn't also translate into the history of art through research and writing, that doesn't just end up being part of this story. . So, I think it is important that women researchers and curators not only commit to the practice of women artists or to open spaces for women within museums, galleries, art institutions in general, but also that there is research work about the work of women artists.

From the same museums there is a greater openness to buy feminist art or art made by women. However, as the narratives under which art history is built are still super patriarchal, it happens a lot that pieces by women artists are bought, but then they are not included in the permanent exhibitions.

So, that is why I think that the work to be done has a lot to do with reconstructing the history of art, beginning to understand it from its valuation criteria, from the way in which it has been thought about what is valuable, what is aesthetic, it is a very structural work, to generate a body of research about these women. I think it happens a bit there, because there is activism, and a lot. If I make a list of female artists exhibiting versus male, it's probably pretty even. But that does not mean that there are the same number of catalogues, or that if you go to the museum you will find the same number of women as men in the permanent collection. The work to do is super rich, it is structural, and that is a huge task: the commitment to research.