ALEJANDRA MONTEVERDE AND CRISIS GALERÍA: MEMORY, BODY, AND TERRITORY

Alejandra Monteverde is the founder of Crisis Galería, an art space located in Lima, Peru. The institution will be part of the RADAR section at the 2025 edition of Pinta Lima, a platform for artists to engage with some of the most pressing discussions in contemporary Latin American art. Crisis Galería will present “stories of resistance, transformation, and belonging.”

How did Crisis Galería begin, and what is the meaning behind its name?

Crisis Galería was born during a moment of profound transformation in Peru’s local art scene. In 2017, when we opened our doors, two significant events took place: the closure of Galería Lucía de la Puente—until then the most influential space in the gallery circuit—and the death of Fernando de Szyszlo, considered the most influential Peruvian painter of the last century.

This moment represented a crisis in the most essential sense: a breaking point where the old is dying while the new has yet to be born. I saw this void as an opportunity for a new artistic generation to emerge and find its voice.

Crisis’ curatorial vision promotes a space for contemporary reflection grounded in a critical understanding of the social, political, economic, and cultural contexts in which we live. We are immersed in an era defined by simultaneous and interconnected crises: the rise of authoritarian movements, the accelerating climate emergency, and massive migratory displacements—phenomena that feed into one another and shape today’s complex global landscape.

-

Alejandra Monteverde

Peruvian art is experiencing a decade of consolidation: rising collecting practices, professionalism, and international visibility. What role has the gallery played in this context?

Crisis Galería has played a fundamental role in the consolidation of Peru’s artistic ecosystem and its international projection. From the beginning, we’ve focused on two strategic fronts: positioning emerging artists within the global art circuit through participation in international fairs and exhibitions, and developing a local exhibition program with strong conceptual and formal foundations.

Our curatorial approach is oriented toward critical proposals that explore affective territories, often challenging dominant trends in the contemporary canon. A key milestone in this direction was becoming the first Peruvian gallery to represent an Indigenous artist, Santiago Yahuarcani—a decision that reflects our commitment to diversifying voices within contemporary art.

-

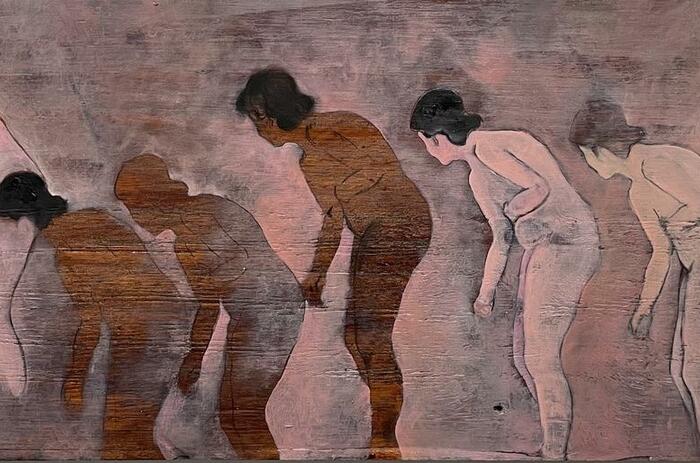

Luz Maritha Rodríguez. Cortesía de Crisis

What are the challenges of running a gallery in a smaller market, and what tools have you used to face them?

The challenges of operating a gallery in a market like Peru’s are considerable. We face a significantly smaller specialized audience compared to cities with longer artistic traditions. In a country where state investment in culture is limited, there is insufficient development of audiences interested in visiting art spaces, which in turn reduces our potential base of collectors and clients.

This reality pushed us, early on, to actively seek international markets for our artists. It’s a frequent paradox—not exclusive to Peru—that local artists’ work is often more valued outside their home country.

When competing internationally, we deal with considerably higher operational costs, especially when participating in European fairs, where we've concentrated much of our strategy. Nevertheless, we have found institutions abroad that are genuinely interested in the work of our artists, and this motivates us to persist in that direction.

Where do you see the Peruvian art market heading? Are there new audiences?

We are at a moment of particular uncertainty regarding the impact that current public policies will have on the country’s cultural development, which inevitably raises questions about the evolution of the Peruvian art market in the near future. Peru presents an interesting paradox: despite recurrent political crises, the economy tends to maintain a certain stability—at times functioning as a kind of bubble isolated from institutional turbulence.

Still, in this ambiguous context, I maintain a fundamentally optimistic vision. I see with enthusiasm the emergence of fresh initiatives and new spaces led by younger generations. While our scene is smaller than other Latin American centers, it stands out for its vitality, resilience, and notable potential for growth.

A promising phenomenon is the growing interest from international agents who come to Lima to meet our artists and immerse themselves in the local scene. This external gaze represents not only a form of validation, but also concrete opportunities for dialogue and expansion.

What place do artists working with textiles or ceramics occupy?

Peru has an extraordinary millennia-old tradition of textile and ceramic production—techniques that have seen a significant resurgence in contemporary art in recent years. Artists working in these media occupy diverse positions depending on their specific contexts, but all are part of a renewed global interest in these disciplines.

In the local context, there are still interesting tensions between what has traditionally been classified as “art” versus “craft,” with textiles and ceramics at the heart of this debate. Historically, both have suffered from systematic undervaluation due to being labeled as “minor arts” or crafts—a categorization that has directly impacted both critical and economic appreciation of these works.

Our approach deliberately seeks to question these established hierarchies that have marginalized these forms of expression, understanding that such categorizations are intrinsically tied to class tensions and the systematic exclusion of social groups outside the hegemonic centers of cultural production.

What is CRISIS’ proposal for Pinta Lima 2025?

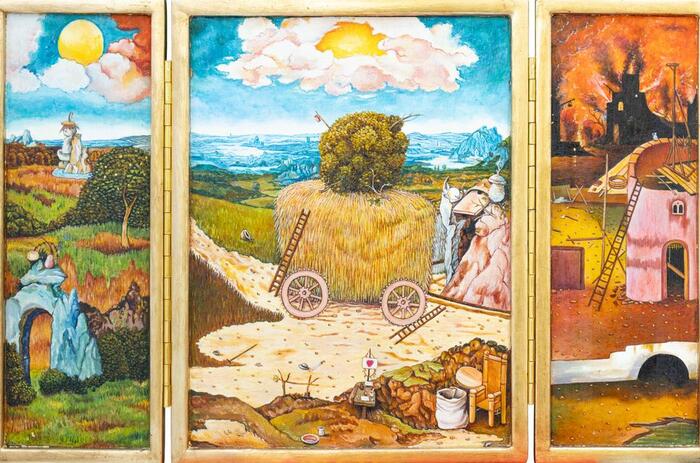

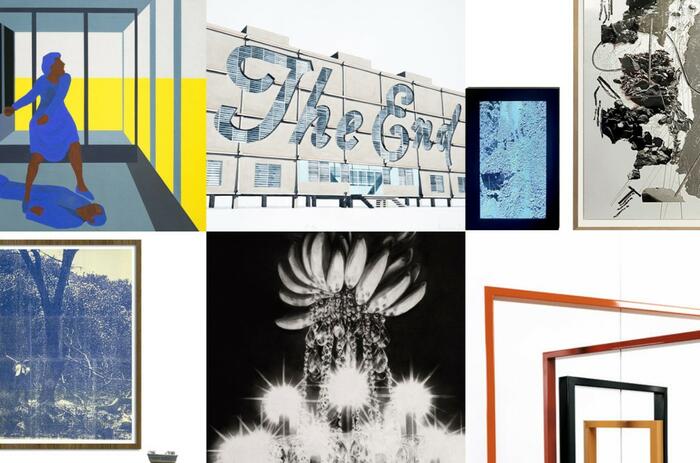

CRISIS presents at Pinta Lima 2025 a dialogue between practices that explore memory, the body, and territory through diverse material and historical languages. Luz Maritha Rodríguez, an Iskonawa artist, introduces a new direction in her textile work, still experimenting with natural dyes but now incorporating new pictorial ranges. These new kere kere—traditional zigzag patterns reinterpreted by the artist—open an unexplored dimension within her practice, while maintaining the spiritual and symbolic connection to her people’s worldview.

Gala Berger exhibits a series of recent collages that engage with historical and decolonial themes through a critical and sensitive lens. By recomposing images and symbols, her works offer a poetic revision of narratives of power and cultural displacement.

Finally, Sergio Murga Rossel’s ceramic compositions explore the aesthetics of fragmentation and material experimentation. By reassembling pieces created over seven years of professional exploration—together with varied glazes and precarious structures—Murga reveals an intimate archaeology of his creative process, questioning the boundaries between finished work and perceived error.

Together, the three proposals speak of art as a vital gesture, where every material tells stories of resistance, transformation, and belonging.