WILD TONGUES: THE ART OF RESISTANCE

Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano coined the term coloniality to describe the ways in which colonialism structures the present. Organized by the University of California Riverside’s UCR ARTS and the Getty Research Institute, Transgresoras: Mail Art and Messages, 1960s–2020s celebrates those in thepositions that coloniality produces but devalues—colonized peoples, racialized and gendered subjects, migrants and diasporas whose languages, knowledge and traditions have been deemed inferior. Centering what Argentine semiotician Walter Mignolo refers to as border thinking [pensamiento fronterizo], the sprawling historical survey foregrounds the desire and defiance of nearly seventy Latinx and Latin American women artists who identify political oppression, economic instability and geographic displacement not as inevitabilities, but as symptoms of systems of power that operate at their exclusion and expense.

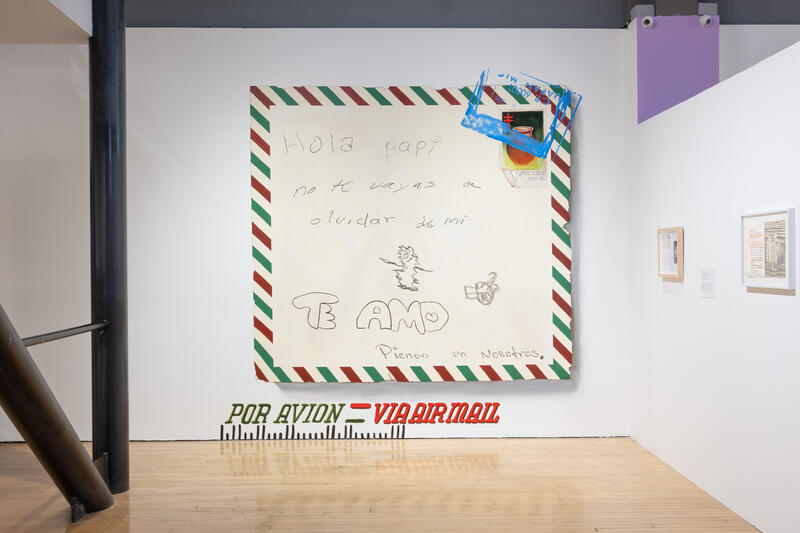

The exhibitionat the California Museum of Photography in Riverside demonstrates a breathtaking depth and breadth of scholarship whose objectives are twofold: to decouple Mail Art—a social practice that employs the postal service as a means of distribution, shifting how art is handled, where it lives and who is allowed to have it—from its gendered homonym, and to demonstrate the movement’s reverberations in 21st century art practices. Works appear in loosely chronological thematic constellations: Mail Art Correspondences and Feminist Collectivity; Visual Poetry Networks; Censorship and Clandestine Communication; Postcards, Paperwork and Rubber Stamping; Communicating With/From the Land; and At a Distance: Migration and Family Separation. Uniting these constellations is their engagement with language as a site of struggle.

-

Lenora de Barros. Poema [Poem], 1979. Offset lithograph. Collection of Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Under censorship, artists whose frustrations cannot be put into words instead articulate silence. In Poema [Poem] (1979), the poetry lies in the human-machine interaction in which flesh resists metal. A vertical concertina consists of six panels, each with a tightly composed black and white photograph taken by Swiss Brazilian artist Fabiana de Barros of her sister Brazilian artist Lenora de Barros. From top to bottom: Lenora’s relaxed lips frame her languid, protruded tongue; tongue licks the keys of a typewriter; pushes up against its steel typebars; fights these sharp moving arms; becomes ensnared; finally, only a cluster of typebars remain in Lenora’s absence, suggesting a painful escape. The Barros sisters refer to theirephemera as a poem: one composed not of words, but by a series of actions and interactions tied to their production.

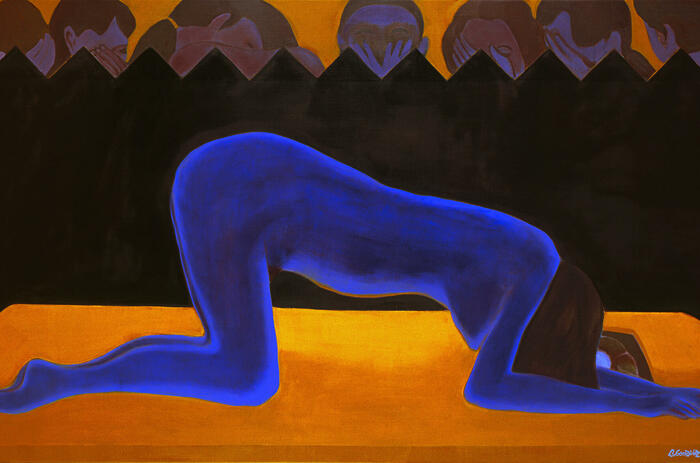

With forceful mark making, Mexican American artist Carmen Argote contends with discourse in the pursuit of empowerment and catharsis, her three horizontal diptychs (2023) echoing Poema’s physical and figurative wrestling. On the left appears Argote’s childhood correspondence with her father, she in Los Angeles, he in Guadalajara. The artist obscures the contents of his letters in black, red and yellow colored pencil, scribbling out words and entire paragraphs and circling the phrases and sentences that remain, each stroke carrying the weight and charge of their separation. In Abril 27, 2001 [April 27, 2001], Argote circles words that imply scarcity and disconnection: “el telefono” [“the phone”] and “poco minutos” [“few minutes”]. In Junio 7, 2001 [June 7, 2001], she circles a sentence that rings hollow, suggesting disappointment and heartache: “Hubiera dado todo por quedarme a su lado” [“I would have given everything to stay by your side”]. With a single yellow line, she crosses out an adjacent phrase, rejecting the resignation and finality of her father’s declaration: “No puede cambiar” [“One cannot change”]. On the right are woodcuts that document action: a soft wood block hit multiple times against the word MOTHER carved on a tombstone, creating a relief. Where the left obscures and emphasizes words, the right deconstructs one. The impact between wood and stone recorded in black ink on khaki paper captures individual letters and their fragments, revealing that even the word mother is pregnant, carrying OTHER and HER within it, language giving birth to language.

-

Carmen Argote, Junio 2, 2003, 2023. Courtesy of the artist

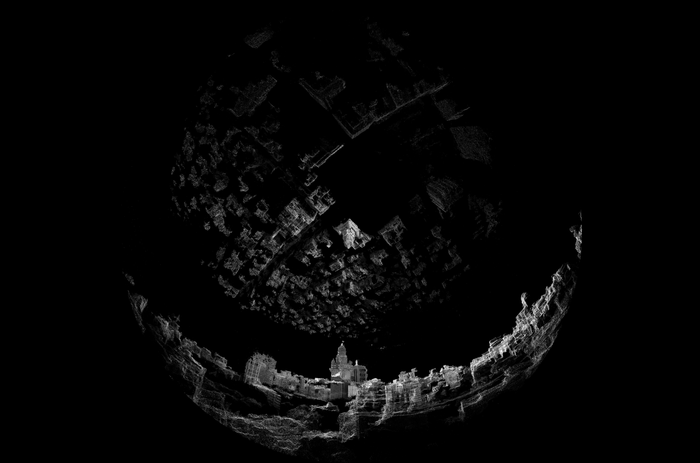

Suspension is a metaphor for the precarity and tension in the artists’ geopolitical contexts. Suspended from the ceiling by a wire, Brazilian artist Mira Schendel’s Objeto gráfico [Graphic Object] (1973) twirls 360 degrees. The double-sided mobile consists of two sheets of clear acrylic that sandwich translucent paper with several sizes of Letraset type applied to both faces. Like particles, the letters cluster and disperse, appearing to float despite being fixed. In a video of Lo voy a gritar al viento [I am going to scream it to the wind] (1999), Guatemalan artist Regina José Galindo is suspended from the arch of the Palacio de Correos, Guatemala City’s central post office, reading poems, tearing out pages and casting them to the wind in a confrontation with futility. Documented in a photo, Salvadoran American artist Beatriz Cortez’s NO CAGES NO JAULAS (2020) employs skywriting over a Los Angeles Immigration Court to protest the cruelty of the U.S. government’s family separation policy. Written in smoke, letters form and vanish into the atmosphere. As the smoke dissipates, meaning is literally up in the air, suspended between legibility and disappearance.

The emergence of Mail Art in the second half of the 20th century owes itself to postal infrastructure, which enabled artists to circumvent censorship and circulate their work. The rise of authoritarianism in the 21st century erodes this infrastructure. Greeting the viewer before the entrance to the gallery, American artist S.C. Mero’s Vote-by-Mail [Voto por correo] (2020) tags the exhibition with an immediate asterisk. A replica of the blue USPS collection box, whose legs are extended like stilts, towers over the viewer and looms just above the adjacent partition wall, remaining partially visible from within the gallery. The collection box’s inaccessibility warns of the danger of dismantling the post: disenfranchisement. Unable to send international shipments through IPOSTEL, her country’s postal system, Venezuelan artist Magdalena Fernández relied on two foreign courier services to transport her works to the exhibition, referring to mailing them asan “act of faith.” Hung vertically, the two screenprints on squares of acrylic, only one of which arrived in time for the opening, juxtapose transparency and opacity. In 4sAF025 (2025), bold white frosted lowercase letters including a, d, e, o and t are layered upon each other, remaining decipherable as light bounces off the exposed portions of the acrylic’s reflective surface. Entirely blacked out, 5sAF025 (2025) reveals no information. Opaque matte ink occludes its shiny substrate, absorbing light while reflecting nothing back. Together the works, one of visibility, the other of obfuscation, mirror the respective and opposing objectives of the oppressed and the oppressor. Both Mero and Fernández draw the viewer’s attention to crumbling postal infrastructure under governments bent on the unbridled control of their people, signaling that universal service among national postal systems is under threat.

Chicana writer Gloria Anzaldúa’s mantra of discursive resistance flips the word wild to affirm idiolects that originate at the border: “Wild tongues can’t be tamed, they can only be cut out.” Visceral, seductive and violent, the writer’s statement rallies the marginalized under the banners of disobedience and refusal. As a title, Transgresoras exercises Anzaldúa’s logic, subverting the language of the oppressor to lay women’s claim to defiance. As an exhibition, it illustrates Anzaldúa’s point, that the flame of language burns brightest at the border. Dovetailing with the global rise of authoritarianism, the historical survey champions the border thinking of women artists who employ discourse not as an instrument of subjugation, but as a material and site of possibility, intellectual engagement and discovery. In articulating silence, wrestling with words, deconstructing meaning and suspending belief, artists invent new linguistic ecologies that embrace the body. Where dominant systems of power thrive on certainty,the exhibition holds space for contradiction and difference, presenting a kaleidoscopic feminism whose agenda collide and refract.

-

Installation view, Transgresoras: Mail Art and Messages, California Museum of Photography, 2025. Photo by Nikolay Maslov, courtesy of UCR ARTS

Transgresoras, which closes on February 15, will tour nationally from February 2027 to September 2028 with the support ofArt Bridges. The exhibition catalogue co-published by UCR ARTS and X Artists’ Books is available for pre-order.