GRAPHIC DESIGN, JUDGMENT, AND VISUAL CULTURE IN THE CARIBBEAN AND LATIN AMERICA

The visual culture of the Caribbean and Latin America cannot be understood as a homogeneous or stable system; it is a territory shaped by flows, displacements, and symbolic overlaps in which images not only circulate, but constantly negotiate their meaning. Within this configuration, graphic design occupies a particularly distinctive position, as it does not function merely as a tool of mediation, but rather as a practice of judgment that intervenes in how the region represents, interprets, and projects itself.

Beyond its communicative role, graphic design operates as a system of decisions. Every formal, typographic, chromatic, or structural choice articulates a position in relation to the context from which it emerges. In regions marked by colonial histories, intense cultural crossings, and persistent social tensions, such decisions are never neutral. Designing therefore entails taking a stance toward inherited visual languages, imposed imaginaries, and contested narratives.

In this sense, speaking of judgment in graphic design does not mean elevating it to an autonomous aesthetic plane or conflating it with artistic practice in a traditional sense. Judgment here manifests as a form of cultural responsibility: the capacity to decide which images enter circulation, which are legitimized, and how they are organized within the public sphere. Design does not merely produce messages; it produces structures of reading.

-

Sucedió en Piedras Blancas,1958. Programa: División de Educación de la Comunidad (DIVEDCO). Tipo: Cartel educativo. Contexto: Campaña de educación comunitaria. Crédito: El Arte al Servicio del Pueblo, Universidad del Sagrado Corazón

This logic becomes particularly visible in experiences of public communication across the region. In Puerto Rico, the graphic production of the Division of Community Education (DIVEDCO) functioned as a design system with clearly defined objectives: education, health, culture, and civic participation. Its posters responded to specific messages and structured narratives, integrated into institutional programs with broad social reach. Although many of its executions incorporated highly developed visual languages created by artists and printmakers, their condition was that of design: structured communication, applied judgment, and tangible consequences in the public sphere.

In the Caribbean and Latin America, visual culture has historically been a field of negotiation between the local and the foreign, between the global and the situated, between adoption and resistance. Within this context, graphic design has actively participated in these processes—at times reinforcing imported models, and at others reconfiguring them through locally grounded visual languages. This tension is constitutive of the practice itself, and it is precisely there that judgment becomes significant.

-

Emigración, 1954. Programa: División de Educación de la Comunidad (DIVEDCO). Tipo: Cartel educativo. Contexto: Educación social y migración. Crédito: El Arte al Servicio del Pueblo, Universidad del Sagrado Corazón

Similarly, in Latin America, the Taller de Gráfica Popular in Mexico developed a graphic practice organized as a design system oriented toward social and political communication. Its posters, prints, and printed materials responded to clearly defined educational and awareness-raising messages, conceived for mass reproduction and circulation in the social sphere. Far from operating as autonomous expression, this graphic production was structured as a tool for public reading, distribution, and cultural positioning within a specific historical context.

(It is important to clarify that in these cases we are not referring to “graphic art” understood as autonomous expression, but rather to practices of graphic design and visual communication with defined objectives, clear structures, and public responsibility. The presence of artistic languages in execution does not dilute their condition as design; it intensifies it.)

-

Calaveras locas por la música - 1938. Colectivo: Taller de Gráfica Popular. Tipo: Cartel impreso. Contexto: Cultura popular y comunicación social. Crédito: Art Institute of Chicago

This approach deliberately distances itself from a market-driven or purely aesthetic reading of design. When design is reduced to style, trend, or productive efficiency, it loses its cultural density and becomes interchangeable. Critical design practice, by contrast, acknowledges that every graphic decision has consequences that affect the construction of identity, the distribution of symbolic power, and the establishment of visual hierarchies.

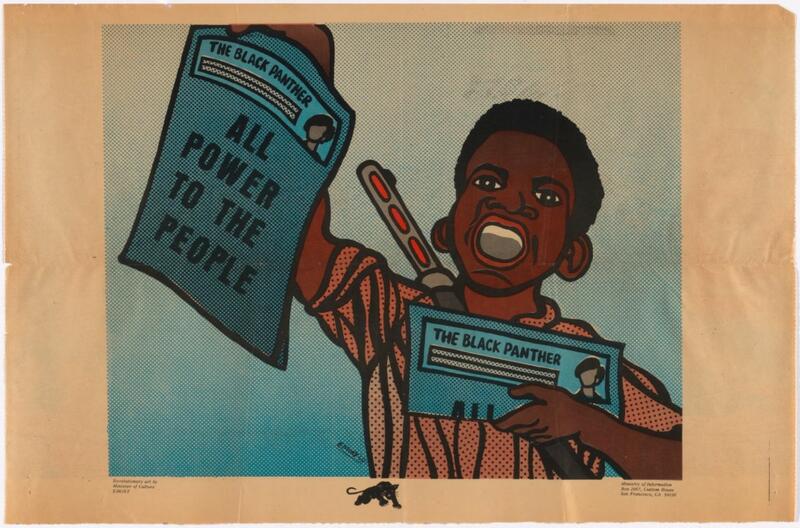

A similar phenomenon can be observed in graphic practices developed in the United States during the second half of the twentieth century, where design was used as a tool for critical engagement with the social environment. The graphic work of Emory Douglas, as art director of the Black Panther Party newspaper in California, articulated direct, legible, and urgent images intended for mass circulation. This was not autonomous expression, but design applied within an editorial system with clear political messages, in which every visual decision responded to context, audience, and distribution.

-

The Black Panther: Black Community News Service - 1969-1976. Diseño: Emory Douglas. Tipo: Sistema gráfico editorial. Crédito: The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Even in contexts where visual language approaches widely recognizable cultural codes, design retains its condition as structure and judgment. The graphic work of Sister Mary Corita Kent in the United States employed design strategies—text, repetition, serial composition—to intervene in concrete social debates. Her work demonstrates how graphic production can operate within clear communicative systems without abandoning function or diluting responsibility for meaning.

Understood from this perspective, graphic design is not limited to solving communication problems; it interprets contexts, translates tensions, and, at times, makes them visible. In an environment where images circulate rapidly and are consumed without friction, the designer’s judgment acts as a filter that can either reinforce superficiality or introduce density, pause, and meaning.

In contemporary debates on visual culture in the region, graphic design often occupies an ambiguous position, frequently displaced into an instrumental role while art assumes symbolic weight. Yet this separation is increasingly unsustainable. Contemporary graphic practice actively participates in the construction of cultural discourse—whether through publications, visual identities, editorial systems, or interventions in public space.

Recognizing graphic design as a practice of judgment within the visual culture of the Caribbean and Latin America does not mean dissolving its disciplinary boundaries, but rather strengthening them. It implies acknowledging that design does not operate outside history or context, and that its value lies not solely in the clarity of its message, but in the quality of the decisions that sustain it.

In a region where images have been—and continue to be—tools of representation, control, and resistance, it is imperative that graphic design assume the responsibility to act with critical awareness. Not as an isolated authorial gesture, but as a practice that understands its place within complex cultural systems. In this understanding, judgment ceases to be a technical skill and becomes the ethical and cultural core of the discipline.

Visual and documentary references

Community Education Division DIVEDCO, Smithsonian Institution

Taller de Gráfica Popular, Art Institute of Chicago

Emory Douglas, Smarthistory The Center for Public Art History