THE NOISY PRESENT AND THE EVERLASTING SILENCE AT DEPARTAMENTO 112

At the Argentine gallery, Pariente by Hans Petersen and Redondita by Juana Cravero engage in dialogue: two exhibitions that explore what we have turned into habit, and the desire that never fades away.

Hans Petersen recently discovered that Che Guevara is a relative of his. In fact, the young Argentine artist had known it for some time, but only confirmed it a few months ago. With that genetic backing, his ironic, burlesque, and denunciatory works are presented at Departamento 112 under the title Pariente.

Bolivian masks hang on the walls, embroidered in Chinese characters that read “made in China,” printed with American cartoons, or covered with flags that do not match the wool they touch. Their titles are ironic, their appearance confusing. Their movement is now bound by new threads that draw Winnie the Pooh, The Simpsons, or Marilyn Monroe’s face upon them. What overlaps is repulsive, and yet it spreads around, infecting its surroundings with its immense voice, its pose, “its precise word, its perfect smile,” as Silvio Rodríguez sings in Ojalá. They don’t merge — one remains above the other, one beneath the other.

The room is noisy, dense with works and ideas. The noise might come from the cries for help of these masks, prisoners long before arriving here. But that might not be the only reason. In the middle of the room stand two large PVC balloons, phallic-humanoid in shape, ready for love or for war. They are Los hermanos cambio (2025), who do not choose their own fate — those who dare to skillfully manipulate, or simply pull, their puppet strings hanging from the sides of the space will decide for them. Yet little sound comes from the brothers themselves; it is their expectant crowd, waiting for any movement, that deafens the space — like the audience at a cockfight, eager to see if the one they bet their savings on will win.

Perhaps the noise cannot be explained there either, but rather in the insistent plea scattered across the floor: “DO NOT LOSE FAITH IN ARGENTINE ART,” written in all caps on photocopies. Much like Alejandro Casona’s rule “Forbidden to Commit Suicide in Springtime,” both demands, beyond their tragicomic tone, reveal a desperate final prayer.

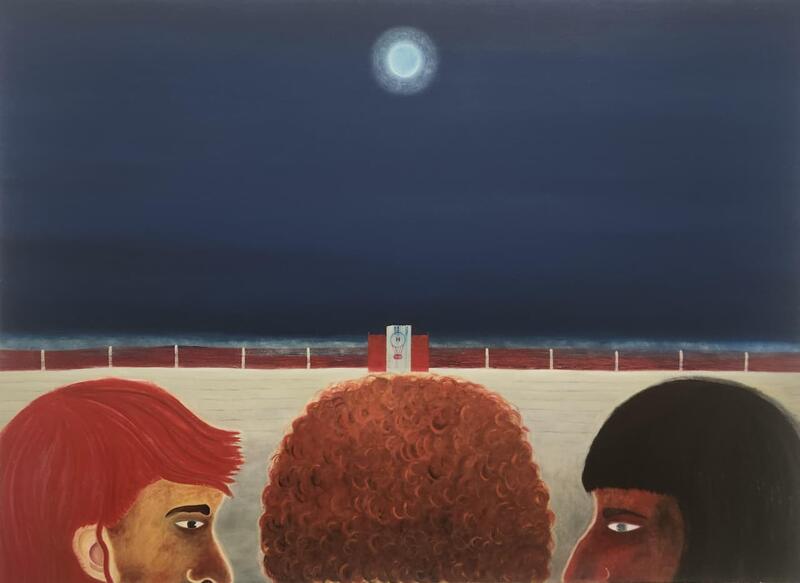

The adjacent room, where Juana Cravero’s Redondita is shown, hears nothing. It is suspended in time, within its own bubble. These are mundane, familiar, recognizable scenes, and yet they seem to belong to the world of dreams. They are pauses: a foul that leaves a player on the ground, an embrace between numbers 10 and 19, the contact of a crowd that already knows itself. If one stares long enough, that fresh green grass begins to turn into mud; one can hear the secret shared between 10 and 19, and smell the sweat of the stands. Nothing overlaps here—perhaps things only juxtapose. Everything is about encounter: between the everyday and what drifts in a balloon, between what one desires and what the rival wants, between the dream asked of the moon and the reality of mud.

In Skay, a typical soccer scene unfolds in the background, yet what comes before it is an image both intense and tender: a man and a dog gaze at each other — deeply, intensely, intimately. Whether one owns the other or not, that look had been promised; it carries the responsibility of shared courage. Into a world worthy of Sacher seeps an Arltian dog — as neighborhood fauna, as mirror or reflection, as the familiar.

Whether imposed or agreed upon, whether overlapped or juxtaposed, at Departamento 112 the known and the disruptive wrestle; dream and routine play their match. The closeness of a distant relative justifies the act of denunciation, while the gaze between a man and a dog brings the faraway world closer.

Hans Petersen: Pariente and Juana Cravero: Redondita will be on view through mid-January 2026 at Departamento 112, Av. Sir Alexander Fleming 1543, Buenos Aires (Argentina).