DEPARTAMENTO 112: A STORY, A BIRD, AN ENCOUNTER

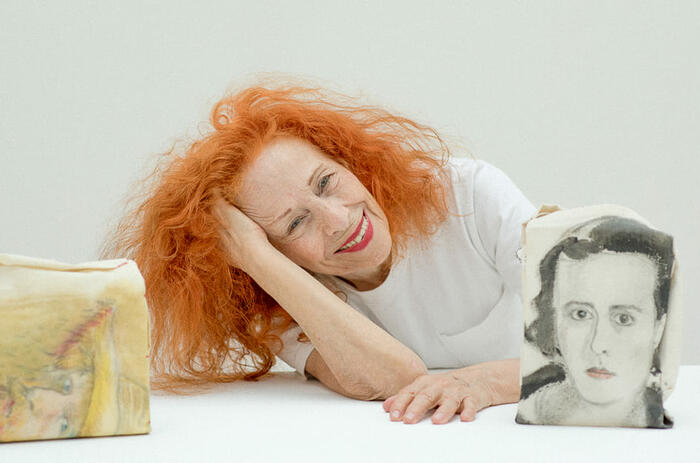

The artist and the gallerist were drinking mate on Fleming Avenue in Martínez, in front of the gallery, trying to hold onto the warmth of a cool autumn sun. That simple, everyday, and sincere image foreshadowed the exhibition at Departamento 112.

A coffee, bread with butter, and a prayer to Gauchito Gil welcomed me into the space. I accepted it all. I visited Departamento 112 for the first time on Saturday. I knew it was a gallery founded and directed by Hans Petersen, with a clear commitment to sharing emerging and idiosyncratic Argentine art, and that it also operates as a creative agency for design and image. What I didn’t know, and believe I’ve come to understand, is that in every sense, the gallery seeks encounter.

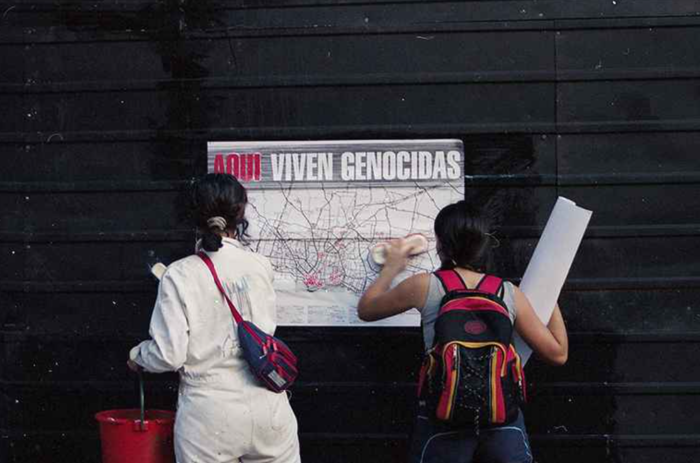

The opening featured two exhibitions. The first was a solo show by Mariano “Rojito” Podesta, who tells Argentine myths through spreadsheets, metalwork, and archival materials. Several of us gathered around to listen as the artist narrated the stories that contextualized his works. His storytelling revealed a relentless curiosity and an overwhelming drive to recover what’s been forgotten, even though his pieces were arranged in a slow, deliberate way. “Am I going on too long?” the storyteller asked. “No, keep going,” we, the audience, replied. A light blue enameled iron Argentine flag stood in the center of the room, inspired by the logo of a contemporary art museum once imagined for the Malvinas Islands but never realized. Behind a wall hung the archival materials of that story: a magazine article from Arte al Día announcing the museum that never came to be, and the graphic designs by Jorge Canale. Here they were, hidden behind everything—what we don’t always see: the sources behind the materialization of ghosts. With the full story in mind, I asked the artist for the title of the piece. “Untitled,” Rojito replied, having recovered a forgotten story but choosing not to name it.

In another room, there were crustless sandwiches, medialunas, cookies, and more coffee. People were at ease, chatting around a large table. And I imagined what that museum in the Malvinas might have looked like, and how I would have liked to visit it. I also wondered what artworks might have been included, beyond Rojito’s work leading the building.

I moved on to the second exhibition, fresh and labyrinthine, diverse in styles and approaches. According to Hans’s explanation, it features 23 national and international artists selected for the Second Acquisition Incentive Prize, who, in some ways, are part of the engine that drives the gallery. I went over the artworks several times, circling the installations. One piece in particular moved me: a kind of tent, its fabrics decorated with bird figures, upon which, curiously, a large fly had landed and was walking in circles. Next to the tent, a book opened to the first page read, “I’ve never seen so many dead birds.” So I looked again at the figures: featherless birds, rigid legs, black eyes, and silent beaks. Ah, such brutal simplicity, such pain, such beauty. I thought of the many little birds my cat has brought me, the ones I rush to check if they’re still alive, and the stains left on my windows by pigeons crashing into the glass, and the many bodies I’ve found in my garden, victims of my dogs’ teeth. My body shudders; I feel small, uncomfortable, and cruel. I step back and continue walking.

Hans takes us through the next rooms and talks about future plans he would like to realize. I realize that Departamento 112 is ambitious in its vision, but never tries to be something it’s not. That’s the feeling it gives. A gallery that captures a young audience and allows that audience to encounter its own history and its everyday life. Because it’s in the everyday that we also find what’s truly ours.

I wasn’t there long, and I instantly regretted leaving so soon. I walked back along that avenue in Martínez, trying not to look too closely at the ground—I was afraid I’d see a dead bird.