CHRISTIAN VIVEROS-FAUNÉ: “LATIN AMERICAN REPRESENTS A CRITICAL AND PRIVILEGED STANCE TOWARD POWER FROM THE ‘MARGINS’ OF THE EMPIRE”

Christian Viveros-Fauné (Santiago de Chile, Chile, 1965) is, for the second consecutive year, at the helm of Foco LATAM, the section through which CAN Art Fair Madrid—celebrating its tenth edition this year—aims to strengthen artistic and cultural industry ties with Latin America. Isabel Croxatto, Klaus Steinmetz, The Cuban Art Hub, Proyecto NaVa, MORFO, and Praxis are the galleries that will present their proposals in the program, showcasing Latin American artists framed within the curatorial line of New Surrealisms.

The Chilean curator speaks with us from his residence in New York to delve into the key aspects of the project and to expand on notions and ideas surrounding the influence of Latin American art today.

Álvaro de Benito [A.B.] In the critical text for this edition of LATAM, you propose structuring everything around a semiotics that goes beyond the definition of surrealism as an artistic or literary genre, as if through a semantic revision one could access a reality that may already be there. How can this be embodied in the curatorship of a program such as Foco LATAM at CAN?

Christian Viveros-Fauné [C.V.] As at the beginning of the twentieth century, visual art and culture in general are being produced in a moment of great uncertainty, similar to that which the original surrealists responded to: from how to render an image to epistemological and ontological questions. This is why it is no coincidence that the world’s major museums, among them MoMA and the Moderna Museet, are experimenting with and revisiting the idea of surrealism at this moment.

A.B. What role would Latin American art play within this framework, considering that Latin American art is increasingly less geographical and less homogeneous for audiences, in contrast to a European or North American revision of another surrealism?

C.V. You are right to say that the LATAM area itself is composed of regions, but insofar as a geo-cultural position can be articulated, so to speak, Latin Americans have very often positioned themselves as a counterpoint to factual power structures. It is a view of authority seen from what the empire understands as the margins, but which also constitutes a critical and privileged position vis-à-vis power; this continues to occur today, even with the greater internationalization of Latin American art.

A.B. The purely Latin American essence seems to be fading, as the industry permeates it with European and North American concepts, but at the same time that original component is being reclaimed. There is talk of the Amazonian, of textiles, of craftsmanship, although we are facing a broad production that has been developing for decades in a different context. How can these two issues be alternated in order to achieve the right balance?

C.V. It is a good question, and I believe it will be well represented in Foco LATAM at CAN. These epochal shifts are important both for those who receive and those who produce. In this way, the path widens both for Latin Americans and for Europeans and, specifically, for Spaniards. The United States currently chooses to reject Latin American culture as a servile culture or directly as trash or garbage. Spain, for its part, becomes a refuge or vessel for the American and Spanish-speaking immigrant population in a way that is unique in Europe and the rest of the world. From Latin America we often speak of the realm of the surreal—understood here as the Macondo of the 1970s and El agente secreto, the recent film by Kleber Mendonça Filho—and that word fits within a history of the everyday turned upside down, as a perversion of the normal order. These ideas can be very fruitful. On the other hand, the notion of right-wing culture has already arrived; we do not fully see it yet, but it will be another manifestation of the geopolitical shift we are undergoing.

Á.B. Tell me a bit more about that distinction in the concept of a right-wing culture.

C.V. Whether we like it or not, it seems to me that we are witnessing the birth of a right-wing culture. There is a normative bias that forms during periods of stability. People assume that this is just how things are, end of story. When there is a sense of normative jurisprudence, democracies function and the law is respected—this creates a certain type of culture. Now, when those values start to be reversed, another culture emerges, another vision of culture. By no means am I advocating for a right-wing culture, I should say. What I do advocate for are democratic processes and perspectives, which art is especially strong at recording as a symbol.

-

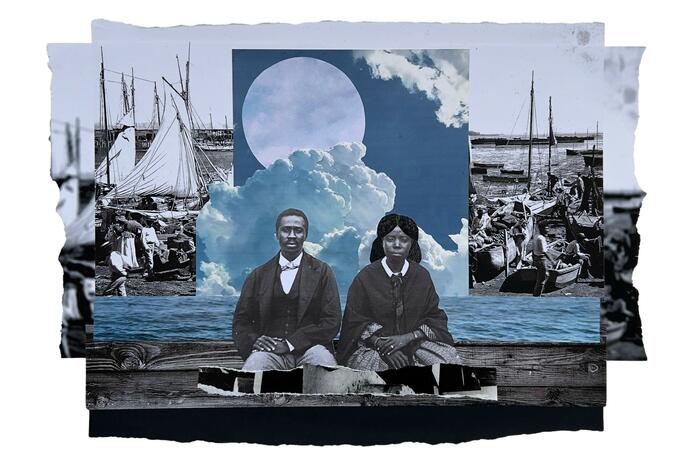

Christian Viveros-Fauné.

A.B. CAN strongly advocates for the relevance of painting, and this may be one of its distinguishing features. In this new renaissance of painting that we are experiencing, where it might seem that it is being reclaimed as the great technique, what can paint—especially Latin American painting—contribute to these dynamics we are discussing?

C.V. Historically, painting has always been the principal medium. It has had its ups and downs in terms of prominence, but there is something particularly important in its process, which is that it slows down the retinal within a historical context of a thousand years or more. Latin America is a region that, in its relationship both with political and military power and with cultural power, has positioned itself as a reference to that power and, many times, in opposition to it. From there arise visions that are more critical of those cultural and political powers through painting. In Spain there was a kind of prolonged rejection of painting, because the conceptual remained very dominant, as did the photographic, and it is precisely Latin American work that is capable of opening paths and articulating other possibilities.

A.B. Beyond surrealism as a conceptual framework, have there been other lines guiding your approach in curating Foco LATAM?

C.V. The two-dimensional image is easier to manage at a fair, but there is a conviction to bring all kinds of imaginaries, ranging from works that I understand as a kind of new vision for what is to come. One must understand that the threshold of the surreal is also designed to be quite generous. There is no other way to curate a fair, because a fair is not a museum exhibition. But it does seem important to me to introduce a critical turn—not necessarily theoretical—to facilitate access for both experienced and lay audiences.

A.B. In your selection of galleries and artists, was there a stronger criterion of novelty and discovery, or, on the contrary, was there a tendency to reaffirm the Latin American dimension and its economic viability within a fair?

C.V. The surprise it brings will always be a point of interest for the viewer. Ideally, one should be able to offer the public a range of possibilities, both established artists presenting new work and emerging figures being seen. We must be able to propose points of comparison, not necessarily in terms of quality, but in terms of different visions.

A.B. What difficulties have you encountered in consolidating your initial conception of the curatorial project?

C.V. The art market is not particularly buoyant for the middle classes in the United States, in Europe, or even less so in Latin America. Shipping costs are high, and the difficulties are what they are. So perhaps that has been the greatest challenge.

A.B. Perhaps all of this also influences the materialization of the conjectural plane.

C.V. That also has an impact on theory. The ideas one would like to realize are limited by the material that is available. But we have been fortunate both in this grouping and in the one we did in the inaugural year, in 2025, where very good galleries came together along with some excellent artists who, moreover, were rewarded for it. Fairs serve to create markets, for important gallery projects and for new artistic proposals, but it is much more difficult to bring work from Argentina or Chile than from Spain.

A.B. What do you think Foco LATAM can contribute in terms of differentiation from other curatorial initiatives around Latin America present at other fairs?

C.V. Some fairs no longer advocate for the old regional focus, and the fact that this has changed and that another focus exists can be a difference. You do see groups of Latin American artists or galleries, but I do not know whether that approach within the proposal achieves the level of interest it did in previous years. For example, years ago the presence of Peru linked to a particular collection at fairs, or at other times Brazil or Mexico, seemed spectacular to me. Perhaps that direction, with an exclusive focus, felt more solid to me.

Foco LATAM is a program of CAN Art Fair Madrid. It can be seen from March 5 to 8 at Matadero Centro de Creación Contemporánea, Legazpi 8, Madrid (Spain).