IRISH PAVILION AT THE VENICE BIENNALE

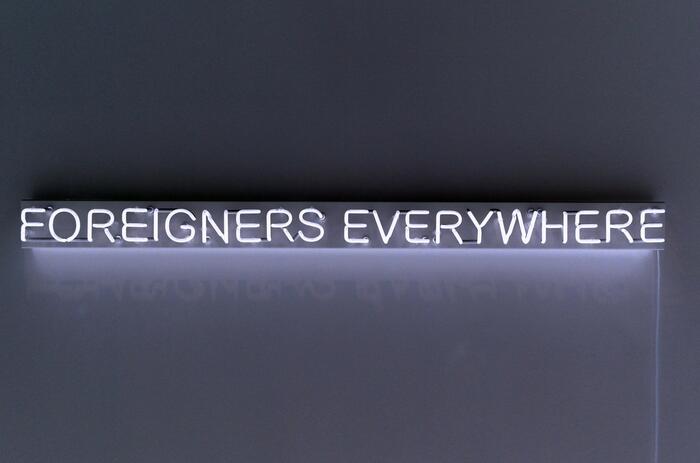

Ireland at Venice will present ROMANTIC IRELAND, an exhibition by Eimear Walshe, for the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, curated by Sara Greavu and Project Arts Centre.

Through a practice that spans video, sculpture, publishing, sound, and performance, Eimear Walshe’s work traces the legacies of late 19th century land contestation in Ireland and its relation to private property, sexual conservatism, and the built environment.

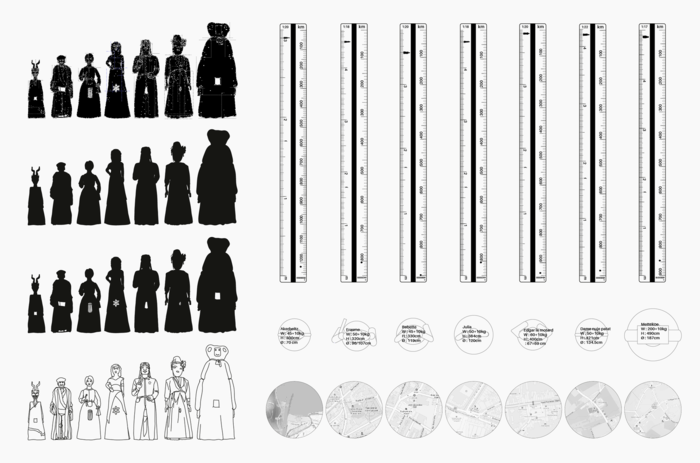

ROMANTIC IRELAND comprises a multi-channel video installation and an operatic soundtrack housed in an immersive sculpture. Set on the site of an unfinished earth build, the video stages soapy, dramatic encounters between character archetypes from the 19th–21st centuries. These figures occupy an abstracted ruin, a site under simultaneous construction and demolition. The pavilion soundtrack is a five-voice opera describing the scene of an eviction, composed by Amanda Feery with a libretto by Walshe.

Walshe’s project for Venice explores the complex politics of collective building through the Irish tradition of the meitheal: a gang of workers, neighbors, kith and kin who come together to build, harvest and cooperate in mutual aid. It depicts a frenzied and fraught engagement with the ancient labor-intensive practice of earth building, a form of construction with an 11,000-year history and local iterations across the world. The video work was shot on location at sustainable skills center, Common Knowledge, on Ireland’s west coast. Led by choreographer Mufutau Yusuf, a group of seven performers, including the artist, enact characters in constantly rupturing historical dyads. This was filmed on four mobile phones passed between each actor, blurring the traditional distinction between director, performer, and camera person.

Made in the shadow of the ongoing housing crisis in Ireland, the installation becomes, variously, a building site of possibility, a wrestling ring for Ireland’s generational and class antagonisms, a space of tender care, and a structure made into a cold ruin by the social death of eviction. The exhibition forces encounter between historic moments, and draws out their parallel power dynamics and affective registers; their forms of labor, conflict and pleasure; the entangled histories of sexuality, property, and the state.

“There are a lot of insights from Irish history that we owe it to the wider world to share. Life on the island—its history of colonization, revolution, and partition—provides so many opportunities to re-enact historical traumas, so many invitations to betrayal of our past, our neighbors, and ourselves. We are a colonized nation, and yet we aid in the colonization of others. Some of us were dispossessed, and went on to do the same ourselves. History doesn’t split the difference. This is where the work for Venice emerges from.” — explains Eimear Walshe.

“Walshe’s work draws on the swelling Irish cultural revival, but is not nostalgic. It is not nativist or relying on imagined mythologies, but is opening out and reconfiguring, sensitively displacing and embracing these elements as it prefigures alternative social relationships.” —states Sara Greavu, curator.