GABRIELA AYZA ASCHMANN: HER CALL TOWARDS WILD (LIGHT)

The Spanish-German artist Gabriela Ayza Aschmann (Cologne, Germany, 1991) presents in Tomas Redrado Art a series of paintings created in 2022, as an experience of inquiry into the expanded borders of portraiture that strengthens her. It is a sustained practice that she carries out advancing against the background of the history of the avant-garde, but above all she acts as if she were tearing pages from her own life, to add them to art.

Her paintings contain autobiographical clues, including revealing phrases ─sometimes transgressive─ handwritten in the margins, and have a specular function: they are images of herself built from self-portraits or found faces of other anonymous women, but they are also ontological portraits that reflect a generation born and shaped among multiple modes of dislocation. They are paintings that oscillate between figuration and abstraction, and balance between the creation and destruction of forms and their meanings.

She searches for a language capable of enunciating a truth that she does not possess, but that she pursues relentlessly in every line and figure: she is willing to represent the desire of bodies over and over again, but she also encrypts signs of disenchantment in her language; the ultimate impossibility of reaching another being, perhaps. And, furthermore, to descend into the abyss of the human condition, she covers the distances that separate us from the other kingdoms, and paints in the images of plants or insects her own reflection, or that of the entire human species. Like Frida Khalo, who portrayed the hardest moments of her life in her still life paintings, Gabriela Ayza paints herself, like someone who ties herself to flowers, sisters to herself, knowing that the immortal spirit is in all beings.

-

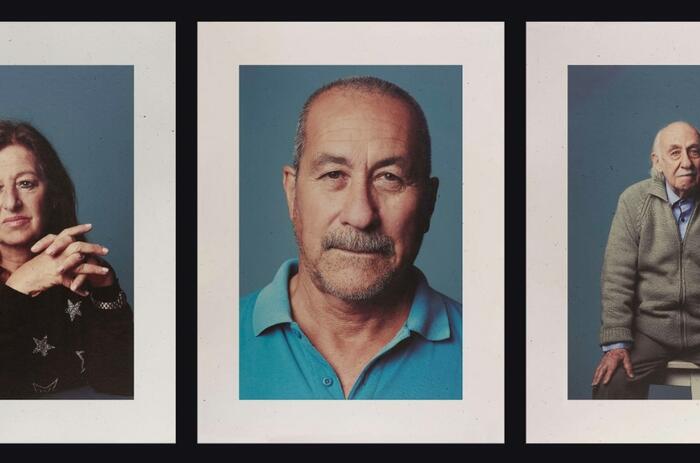

Vista de instalación. Snakehead, 2022. Gabriela Ayza Aschmann. Oil on canvas - 109 x 168 in. Imágenes cortesía de la galería.

Her multiple attempts at a language that emerged from facing existence instant by instant, resume in her own way the saga of her predecessors in the history of art: those women artists ─like Marlene Dumas or Kiki Smith, or like Tracey Emin, for example─ who, for decades, have used painting (among other media), particularly of the body, as an anatomy of their emotional life, as a means to make erotic-affective dissections that contain the ethos and contradictions of contemporary culture.

Gabriela Ayza has renounced separating art and life aseptically: she allows images from the archive of her own life to slip into her artistic fictions, and in her desire to see it without masks, with all the required rawness and with a burning thirst for something beautiful, she resorts to a detailed magnifying glass ─sometimes so close that it produces a distorted vision─ and bends over herself to observe herself, to take a picture, even in close-ups of the flowers. A key self-reflexive, meta-artistic work is Still Painting Flowers. She pursues and finds herself in neo-expressionist paintings, where she portrays herself not only unfolded in other bodies that are a mirror in which to observe herself, doubles of her, but also in still lifes with flowers that have bled ─she is sure of that─ when being cut. Perhaps she thinks that they can utter words that are as unintelligible as they are terrifying, but she also leans over them by painting their image and listening to a coded message, something important that perhaps flowers and plants have to tell us.

Between the paint and the colored blood, dripping in shapes that may have the appearance of a forest or a body, there are areas of stains, gestures that drip the expression of something that is never named, but that spills paint to painting (The extreme edges of her works ─which can sometimes be seen on the sides─ contain spots or words that are like small entrance doors to each scene). It is not the love that inevitably flees, it is barely touched: in her paintings the hands are sometimes an indefinite form that dissolves into another body without having the ability to grasp, to really touch anything. They barely touch each other's hands or are raised up gloved, or not in the field of view, as in Silk House, where the arms are hidden under the black fabric, exposing instead the bare, vaguely outlined breasts.

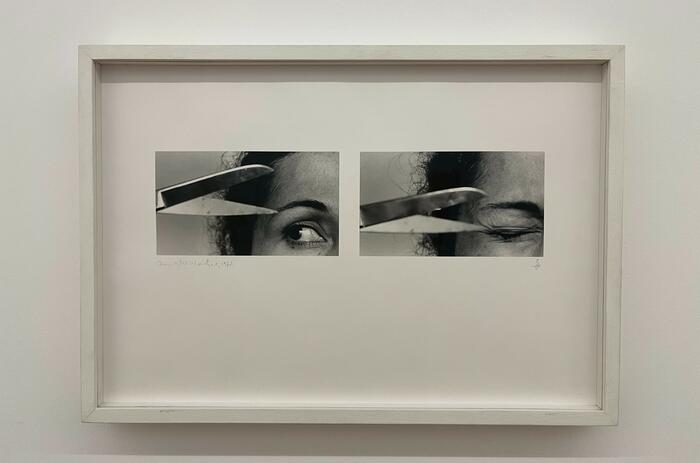

There are spots or shapes that cover or close the senses in various portraits and perhaps they are expressions of the desire to go through them until touching something else, which sometimes enunciates the words in the margins. Because if the language of desire were the only one to articulate its message, nothing would cloud the eyes, the hands would touch, nothing would seal the mouths. Instead, as she writes freehand: "It is always about the body that wants to escape (...) the only object of mercy." Above or below the signs of desire, the unattainable, weighs. The flesh, turgid, so red in some works, is also a matter of suffering: it is the space for a combat in which a mode of negation or the shadow of something that is annihilated ends up being pronounced. There is a completely abstract work, with a marvelous composition, made with small segments that evoke skin, from pale pink to deep brown, with drippings and luminous areas of expanded white, which makes one think of flesh, seen not only from the inside, but from all the light of the mystery of life in the depths of time and is called Never Mom. Gabriela peers in this painting, but also in a video attached to it, into the pink hole in her inner membranes, as if she were reaching out with her own longing into the void to grasp something out of her reach. And she wants to dare to go to the most animal depth, to the limit of the visceral, to touch something on fire that illuminates her from within.

-

Never mom, 2022. Gabriela Ayza Aschmann. 46x59 in. Imágenes cortesía de la galería.

-

Snakehead, 2022. Gabriela Ayza Aschmann. Oil on canvas - 109 x 168 in. Imágenes cortesía de la galería.

-

At the end, 2022. Gabriela Ayza Aschmann. Oil on canvas - 46 x 34 in. Imágenes cortesía de la galería.

-

Catalina, 2022. Gabriela Ayza Aschmann. Oil on canvas - 46 x 58 in. Imágenes cortesía de la galería.

Post-impressionism, neo-expressionism, painting-after painting, photography and transfers of graphic languages to pictorial media that build a fragmented poetics, loaded with irony, and traversed, even more than by desire, by an urgency of truth as an imperative to which her being -able to feel like a spider, a wolf, a bird, a moth without a mouth, and a flower that bleeds when cut─ aspires. What her paintings in pale roses, pinks or grays drip, is a subterranean mode of “pain”. But this word is etymologically linked to passion, and its flame contains what Gabriela remembers of Andrei Tarkovsky: "An impulse towards the infinite, towards the spiritual, towards the truly human" that is only communicable with images. There is beauty in her bleeding flowers even if she cuts the splashing drops and her still lifes only contain a faint trace of what they suffer and/or utter; and there is beauty in the gaze of the women who look at us squarely in their portraits, ready, like her, to burn when looking at the flame of the dark. And ascend to the light.

MOM, LET ME BE AN ANIMAL FOR ONE DAY

Gabriela Ayza Aschmann

TOMAS REDRADO ART

8163 NE 2nd ave

Tuesdays to Saturdays – 11am to 5pm

Until November 26th