POP FOLKLORE IN CHILE: UNITY UNDER THE SKIN

The Chilean gallery Casa Varas hosts Lincura’s provocative proposal: a new way of looking at the “exotic” —and a new way of looking into the mirror.

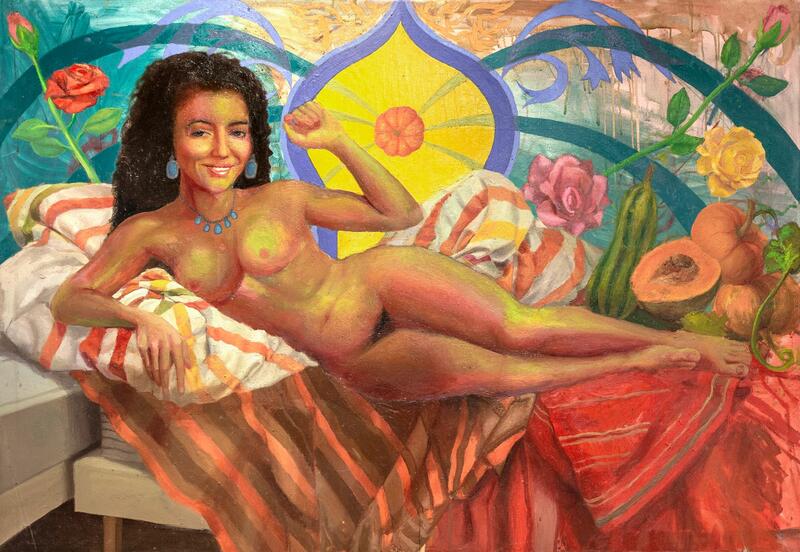

In his exhibition Espejos. La unidad bajo la piel (Mirrors. Unity Under the Skin), curated by Casa Varas and Judas Galería, Pablo Lincura (Concepción, 1987) dismantles stereotypes and builds new narratives, updating folkloric imagery. The Mapuche visual artist works with the human figure and the languages of pop culture to complicate identities, question gazes, and play with what can be transferred. The exhibition gives shape to a new Indigenous discourse.

Huaso, Indonesian Boy, and Mapuche Warrior are three works that mock the stereotypical gaze. The caricature of the “exotic,” the imaginary construct of the other, and the predetermined identity burden all collapse. Lincura laughs at models and clichés. His provocative and unexpected images uphold the permeability and contingency forbidden by archetypes, unsettling the status quo. As art critic Sebastián Marchant aptly puts it, the artist paints “figures that have been portrayed in the media in fixed and closed ways, in order to disidentify them as a political maneuver.”

Kömutuwe (2025), a word that means “mirror” in Mapudungún and gives the exhibition its title, presents two men facing their reflections. One, presumably Mapuche based on his clothing, looks himself straight in the eye—“he sees himself in his own identity, in what is revealed to him when he faces the mirror,” writes Marchant. The other, dressed in Western clothes, looks at him. He does not look at himself. He is not in search of himself. He chooses to gaze at the other. The scene becomes a visual metaphor for two ways of constructing identity: through introspection or through projection. The Mapuche subject finds affirmation in his own image; the Western one uses the other to define himself. In that gesture, a powerful idea emerges: identity is not only what one is, but also how—and whom—one chooses to see.

Throughout the exhibition, a new discourse emerges. Not one that “represents” Indigeneity from the outside, nor one that aligns with what is expected of the Mapuche. Lincura doesn’t explain or translate: he appropriates symbols, mixes them, exaggerates them, tears them apart. He uses humor, queerness, pop culture —and from there, pushes against the ways identity has been boxed in. There is no essence here; there is play, there is politics. Indigeneity does not appear as a relic, but as something alive, contested, and deliberately uncomfortable.

-

Pablo Lincura. Komütuwe, 2024, 150 x 120cm. Cortesía Judas Galería

Espejos. La unidad bajo la piel is on view through July 27 at Casa Varas, Antonio Varas 1181, Temuco, Gulumapu (Chile).

*Cover image: Latina (2014). Courtesy Judas Galería.