THE INFLUENCE AND CONTINUITY OF PRE-HISPANIC TEXTILE ART IN MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART

Textiles–that manifestation constructed from some of our cultures’ softest materiales [1]–are fragile and perishable [2], yet they interweave a cultural paradox because their practice has been resilient and imperishable. Although fiber art is almost as old as agriculture, because it transcended the domain of the merely useful early on to connect to that which is ritual and symbolic, it remains both a timeless mirror and a creative art form that reflects our cultural present, with its hybridizations [3], and with the vestiges of its resistance. To review the history of textiles in ancient America and its connection to modern and contemporary art involves threading the eye to visions that unweave and remake the fabric of knowledge and memory.

Textile art was preserved among the native cultures from all over America [4] generation to generation without disappearing in the maelstrom of the same history that had buried vast architectural complexes [5]. The appropriations of that knowledge were not only crucial in the genesis of modern Western textile art, but continued to be interwoven into contemporary art. Because of this it is essential to trace the origin of this undeniable influence which not belong only to the past, but lives on in the work of indigenous contemporary textile artists, as well as in the art of nonindigenous creators who appropriate this living heritage and sew it into the fabric of our shared present. These explorations will have consequences in the way we construct and apprehend the narratives of art history. The continuity of this inheritance implies also processes of interaction and transformation, marked for cultural hybridization.

In truth, there were “communicating vessels” connecting the refined textiles of the ancient cultures of America and the avant-garde. [6] But the fundamental role of this influence in the modernity of textile art and in its insertion into contemporary art is usually presented in a diluted, imprecise way, which reduces it to the vague mention of the influence that the so-called “traditional crafts”[7] of original South American cultures and other peoples of the Global South played in the formation of celebrated artists. Hegemonic cultures tend to ignore the continuity and validity of the presence and influence of pre-Hispanic indigenous textiles on contemporaneity: it is tacitly stripped of its foundational value; or it is thought of only from an archeological perspective, as a trace of a past; or perceived within the narrow framework of a present where remain confined within the constrict of the production of an “ethnic minority”. But this limited and inaccurate vision is changing, undergoing a critical revision that seeks to include alternative ways of interpreting the past and present of textile art.

-

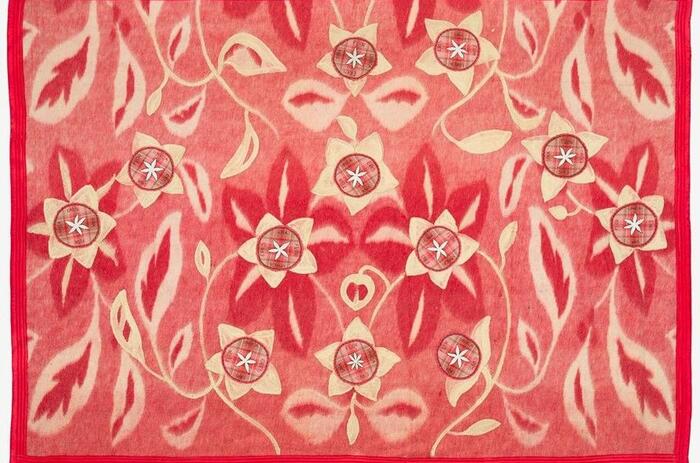

Aurora Molina + Trama textile, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala.

-

Codice Mendoza.

-

Sheila Hicks´ installation. Exhibition Campo Abierto (Open Field) organized by the Bass Museum of Art with the consultant curator Frederic Bonnet. Photo by Willy Castellanos.

-

Casa Flor Ixcaco, founded by Teresa Ujpan Pérez (San Juan La Laguna), Atitlan, Guatemala. Photo by Adriana Herrera.

-

Mayan Weaver at the Chichicaztenango Market, Guatemala. Photo by Adriana Herrera.

-

Sophie Tauber-Arp, Vertical horizontal Composition, 1916

-

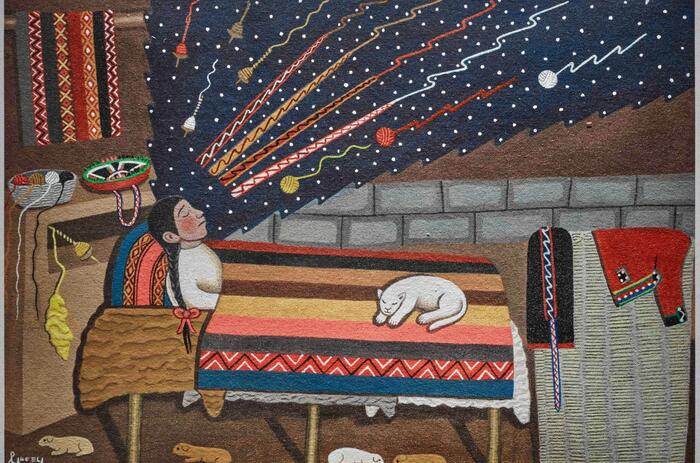

Square in ancient Andes. To Weave for the Sun.

-

America Weaves exhibition at the Coral Gables Museum, Miami, 2018. Curated by Adriana Herrera. From left to right pieces by Miguel Aguirre, Stella Bernal de Parra and Guido Yanitto.

-

Cecilia Paredes, Papagallo, fotoperformance, 2005.

-

Cecilia Paredes, Papagallo, fotoperformance, 2005.

-

Jorge Eduardo Eielson, Quipu, 33 V-1, 1971.

Pre-Hispanic Visions Woven into Modern Textile Art

During the years of the Bauhaus School (1919-1933), the aim was to blur the sharp lines that separated the crafts, applied arts, and fine arts. [8] It is true that, at first, female artists such as Gunta Stölz and Annie Albers had enrolled in textile workshops (the only kind they were then allowed in anyway) because fine art mentors like Wassily Kandinsky would be present. However, these female artists eventually discovered not only the intrinsic value of textile art, but also its power to shape a new era. “Yes!” exclaimed Stölz, “weaving is an aesthetic totality, a unity of composition, form, color, and substance.” [9] But the dazzlement of both the Bauhaus weavers, and the European avant-gardists in general, at what seemed to be brand new, had in fact very ancient roots. And they knew it.

For example, Sophie Tauber-Arp–one of the great artists, weavers, dancers, and choreographers who participated in the Dada events at Cabaret Voltaire–was inspired by the geometric designs of the Hopi Indigenous' costumes and incorporated them into her fashion and art designs in the early 1920s. [10] At the end of this decade, after she left Germany and settled in Paris, she and her husband Jean (Hans) Arp joined the influential Cercle et Carré (Circle and Square) abstract group, started in France in 1929 by the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres García and the Belgian Michel Seuphor. [11] Other notable artists–such as Vasily Kandinsky, Le Corbusier, Piet Mondrian, Kurt Schwitters, and Sonia Delaunay– also joined the group. Distancing himself from the materialist current, Torres García proclaimed that to attain a true universal vision, a “relationship between the most modern and the most ancient” [12] was always needed. For this reason, he gave talks in Paris to members of Cercle et Carré where he explained the pre-Hispanic textile legacy of the indigenous Andes, a legacy that included works that many of them had admired at the 1928 Louvre exhibition of Ancient American Art. [13] It is not uncommon to find, in Delaunay's textile designs, an echo of the textile language of the native peoples from America. “Abstract art is only important if it accommodates itself to the endless rhythm in which the very ancient and the distant future meet,” Sonia Delaunay would indeed assert. [14]

When Anni and Joseph Albers–two leading figures in art who would cause the influence of the Bauhaus to spread throughout the United States–arrived in Mexico in 1934 at the invitation of Cuban designer and artist Clara Porset, they had a revelation that would affect their artistry to the core. “Mexico”, wrote Joseph Albers, “is truly the promised land of abstract art, which here is thousands of years old.”[15] Years later, in the 1950s, Anni Albers would be dazzled by her discovery of pre-Hispanic Andean textile artistry. The excavation of ancient Andean textiles buried for centuries in places like the Paracas (where archeological sites were discovered in the early 1920s) and Machu Pichu (discovered in 1911) had a deep impact on Annie Albers’s career as a textile designer and printmaker. Indeed, she would dedicate her book On Weaving (1965) “to my great teachers, the weavers of ancient Peru.” [16] Those Andean textiles were offered and given as tributes or valuable garments that ten thousand years ago conveyed sacred visions, sealed alliances, and served as ceremonial pieces to accompany the dead on their journey. And they had a powerful influence on Anni Albers´s art: not only in the artworks that she produced that decade, but also in her later jewelry designs and drawings. For instance, she created necklaces in the shape of the Inca Quipus, those pre-Hispanic textiles that constituted a wordless script based on a system of knots, that would become a generating force of other artworks in the 20th and 21st centuries.

From the quipus, the Albers learned that this ancient writing was not only carved in stone, but also woven into fabric, and that its non-verbal signs convey an alternative kind of knowledge. They did not seek to silence this influence that had transformed their work [17] in ways that had tended to be forgotten. They were visionaries who were able to gauge the real scale of the ancient legacy, as well as its persistence: “Perhaps it was that timeless quality of pre-Columbian art that first spoke to us,” [18] Annie reflected when referring to her remarkable private collection of the same, now in the Yale Peabody Museum. And this is a key to approaching the study textile art: understanding that these cultures were not obsessed with the idea of change for change’s sake but instead seek to further and preserve ancient knowledge so sacred that, to them, it was tantamount to a cosmic vision.

Anni Albers, who by weaving felt united to a remote past [19], would not be the only pioneer in contemporary textile art to create by appropriating that legacy. Sheila Hicks, a student of Josef Albers, traveled in 1957, on a scholarship, in search of pre-Hispanic textile art, initially to the Andes, where she completed her thesis. It was precisely in Chile where Hicks first exhibited and sold her art, before becoming one of the great figures of contemporary textile art. In the 1960s she went to Mexico, where she settled and learned about the living Mesoamerican textile tradition, before taking up residence in Paris in 1964. In an interview with Monique Levi-Strauss, she said: “...I was trying to learn how the ancient Andean textiles were made, trying to replicate them.” [20] That “replication” has been key to the recognition of fiber art as one of the means of global contemporary creation; but this precious original source is diluted or omitted in that narrative of art history that is often hegemonically constructed.

Resonances of Pre-Hispanic Textile Art in Contemporary Latin American Art

The memory of the Quipu has lived on through the work of pioneering artists from Latin America such as the Peruvian-Italian Jorge Eduardo Eielson, who died in 2006, or the Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña, both prodigious poets and artists whose series─which took a long time to become internationally recognized─revisited the ancient Andean textile legacy. Eielson's Quipus series honors and evokes the mnemonic system of Peru's ancestral cultures. Eielson had traveled the path of the European avant-garde, including the influence of Arte Povera, to return to that legacy that emerged in the treasured geography of his country.[21] Many years after having held in his hands a millenary reddish fabric woven by weavers of the Chancay culture, in 1965, while living in Italy, he twisted, stretched, cut, burned, and finally knotted fabrics of colored garments to create his own system of knotted fabrics, which he named after the system used by the Incas to cipher messages. His Quipus contained a universal expression, but also, as he told Martha Canfield in 1995, they were “a modest homage to those ancient Peruvians who knew how to turn a primordial gesture into a true and sophisticated language.”[22]

The quipu, certainly, were “part of the development of weaving technology as a primary means of expression”, [23] and today, as Carol Damian has said, “the quipu is alive and is activated by artists such as Cecilia Vicuña.” [24] She conceived “the idea of the quipu that remembers nothing: a quipu that has forgotten the message, because the memory was exterminated.”[25] This idea, not materialized, was the genesis of countless variants of quipus, “knots that speak, and are offerings to conjure and transform reality.” In response to the destruction of the glaciers in Chile, Vicuña made El quipu menstrual in 2006. In 2020, in her exhibition Cecilia Vicuña: Disappeared Quipu (organized by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in collaboration with the Brooklyn Museum) she created an on-site installation that combined a huge red wool quipu she had knotted herself with five ancient quipu–carriers of a nearly extinct language–from the collection at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. Her pieces work by weaving elements of the past into the vision of the future that her messages of resistance conjure up. [26]

Colombian pioneer Olga de Amaral has woven high knots that evoke ancient monoliths, fulfilling her challenge, as a textile master to “weave a rock” [27] in color. Also, she uses gold evoking both its mythical use in pre-Columbian goldsmithing, and the obsession with El Dorado of the conquistadors, who seemed to worship it as a god. Belonging to the same generation and training, Stella Bernal de Parra interweaved in various series the allusions to pre-Hispanic cosmogonies with a geometric vision also connected to the conquest of space, building a language of her own that anticipated the power of textile art in the 21st century.[28]

It would be impossible to name here a sufficiently comprehensive selection of non-indigenous Latin American artists who have woven their work together using the threads of pre-Hispanic textile memory, but I cannot avoid mentioning the Peruvian Cecilia Paredes. In addition to her mastery of cultural camouflage with fabrics, she weaved tying herself with the kingdoms of nature: she delicately sewed chrysalises abandoned by butterflies, revived the art of ancient ritual feather costume-making, and restaged–in powerful, documented performances–ancient rituals that linked animal guides and shamans. Paredes has transformed herself into different creatures, including a peacock and a parrot. There are also contemporary artists like Sandra de Berducy, or “aruma”, who learned ancestral weaving skills from Bolivia’s native peoples, but complemented that knowledge with modern technology and the various lingos that have sprung from the use of new media. The 21st century will see the thread of textile artworks spread along all cardinal points from that America that is a continent full of cultural diversity and where indigenous cultures continue to radiate their influence.

“Funding for this essay was provided through a grant from the Florida Humanities with funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this virtual publication do not necessarily represent those of Florida Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.”

Bibliography

[1] Kazuyasu Ochiai, “The Weavers from Altos de Chiapas. ‘Hard’ and ‘soft’ culture”, Desarrollo de los textiles mayas. https://arqueologiamexicana.mx/mexico-antiguo/desarrollo-de-los-textiles-mayas

[2] Jenniffer Harris says: “Textiles begin to deteriorate from the moment they are made.” Vitamin T. Threads & Textiles in Contemporary Art (London, New York: Phaidon), 2019, 8.

[3] On the concept of hybridization, this “encompasses various intercultural mixtures,” and not only racial ones, to which the term mestizaje is limited, and on its difference from syncretism see Néstor García Canclini, Culturas híbridas. Estrategias para entrar y salir de la modernidad (Mexico: Grijalbo, 1989), 14. An accurate definition of the term states that it “refers to the production of new cultural forms and practices through the fusion of previously separate antecedents.” Michael Dear and Andrew Burridge, “Cultural Integration and Hybridization at the United States-Mexico Borderlands,” Cahiers de Géographie du Québec, Volume 49, n° 138, December, 2005.

[4] In this essay I will be using the concept of America as one continent –from Patagonia to Alaska– in the same way in which the artist Alfredo Jaar did it in his revealing installation A Logo for America, 1987, projected in Times Square, New York City.

[5] Kazuyasu Ochiai, Op. Cit.

[6] Luis Rius Caso, “Leonora Carrington and the Magic World of the Mayans”, Mexico in Surrealism. The Creative Transfusionn. Mexican Arts, No. 64, 2003, 44.

[7] The powerful influence of pre-Hispanic textiles and other cultures on the work of Sheila Hicks is reduced to this term in the press release for her exhibition at the Kunstmuseum St.Gallen, Sheila Hicks, February -May 2023: February –May 2023: “On the one hand, the artist was influenced by modernism, having studied painting under the Bauhaus master Josef Albers at Yale University. On the other hand, she is influenced by the traditional crafts of different continents, which she learned about while traveling and during extended stays in Chile, Mexico, India, and Morocco, among other places”. Thus, the extraordinary influence of the masterful Andean textiles in her work is minimized in the North. www.presseportal.ch/de/pm/100059306/100900247. This was not the case, however, in the exhibition Sheila Hicks. Hilos libres. El textil y sus raíces prehispánicas, 1954-2017, curated by Frédéric Bonnet for the Museo Amparo in Mexico. Also see Carolina Castro Jorquera, Destejiendo a Sheila Hicks, Artishock. https://artishockrevista.com/2019/12/18/destejiendo-a-sheila-hicks-entrevista/

[8] Other art schools advocated that approach: The reformed art school Lehr─ und Versuchsateliers für angewandte und freie Kunst in Munich was, as early as 1910, a place that aspired to attain that synthesis. Artists such as Sophie Arp initially trained in its space and at the Schweizerischer Werkbund. It was there that she met Jean (Hans) Arp. The artists' association Das Neue Leben (New Life) was not far from this vision.

[9] Sigrid Wortmann Weltege, “The question of identity”, Bauhaus Textiles. Women Artists and the Weaving Workshop (London: Thames and Hudson, 1998), 53.

[10] The Ukrainian-born artist Sonia Delaunay, creator of the "simultaneous dresses," was herself a pioneer of avant-garde textiles and fashion in Paris in the 1920s and Amsterdam in the 1930s. Her geometric textile designs for costumes, such as the one she made for Gloria Swanson in 1925, are evocative of the vast textile legacy of ancient America.

[11] He was born Fernand Berckelaers in Antwerp, and adopted the pseudonym 'Seuphor,' an anagram for Orpheus, in 1917.

[12]Joaquin Torres Garcia. "The plane on which we want to situate ourselves", Journal of the Association of Constructive Art. Circle and square. Montevideo, Uruguay, August 1936.

[13] Nosso Norte é o Sul. Our North is the South, exhibition catalogue organized by Bergamin & Gomide in collaboration with Tiago Mesquita and Paul Hughes Fine Arts, São Paulo, Brazil, 2021 (August 21 – October 16), p.11. Torres García saw these textiles in 1922 at the National Museum of History in New York and in Paris, at the exhibition where his son Augusto worked as curator. The avant-garde had also appreciated pre-Columbian art in the middle of that decade at the Museum Für Völkerkunde.

[14] Sonia Delaunay, Nous Irons jusqu'au soleil, Robert Laffont, Paris 1978, p. 46, quoted in Sonia Delaunay, Musée d' Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (London: Tate Publishing), 2014, p.10

[15] Brenda Danilowitz, “No estamos solos: Anni y Josef Albers en Latinoamérica”, Anni Albers Josef. Viajes por Latinoamérica, exhibition organized by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation [curated by, Brenda Danilowitz; Eds. Brenda Danilowitz, Marta González], (14 de noviembre de 2006-12 de febrero de 2007),7.

[16] Anni Albers, On Weaving (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1965). First edition.

[17] The homage to pre-Hispanic architecture that inspires his work To Monte Alban from the Graphic Tectonic series, 1942, is seminal in the later iconographic series Homage to the Square. Brenda Danilowitz, Op.Cit.

[18] Anni Albers, “Pre-Columbian Mexican Miniatures”, Anni Albers Josef. Viajes por Latinoamérica, exhibition organized by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation [curated by, Brenda Danilowitz; Eds. Brenda Danilowitz, Marta González], (14 de noviembre de 2006-12 de febrero de 2007), 27.

[19] Brenda Danilowitz, Op.Cit., 4.

[20] Monique Lévi-Strauss, “Interview with the artist-Entrevista con la artista”, en Reencuentro – Reencounter. Sheila Hicks (Santiago de Chile: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, 2019), 67.

[21] José Ignacio Padilla, “Eielson: materia y lenguaje: quipus”, Hueso húmero, 55, 2010, pp. 23-52. www.academia.edu/10146110/Eielson_materia_y_lenguaje_quipus

[22] Luis Rebaza, “Jorge Eduardo Eielson. El paisaje infinito de la costa del Perú”, nu/do homenaje a j.e.eielson, José Ignacio Padilla, Ed. (Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Fondo Editorial, 2002), 278.

[23] Tom Cumins, “Representation on the Sixteenth Century and the Colonial Image of the Inca”, Writing Without Words. Alternative Literacies in Mesoamerica & the Andes, Elizabeth Hill Boone & Walter D. Mignolo, Editors (Durham and London: Duke University Press) 1994, 96.

[24] Carol Damian, “Fiber Art. Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow”, Circularity of Textil Time (zoom talk), November 17, 28:45, www.youtube.com/watch?v=aonq4ae7DSQ&ab_channel=AlunaArtFoundation.www.youtube.com/watch?v=aonq4ae7DSQ&ab_channel=AlunaArtFoundation

[25] Adriana Herrera, “Cecilia Vicuña. El arte como ofrenda”, Art Nexus No. 115, Diciembre-Febrero 2020. www.artnexus.com/es/magazines/article-magazine-artnexus/5e5692e9a81bfd1d68e93661/115/cecilia-vicuna

[26] Ibid.

[27] Olga de Amaral: To Weave a Rock was also the title of the artist’s first major museum retrospective in the United States, at Cranbrook Art Museum October 30, 2021 - March 2022. https://cranbrookartmuseum.org/exhibition/olga-de-amaral-to-weave-a-rock/

[28] The exhibition Women Weavers, 2018, at Ideobox Art Gallery, Miami, brought together the work of both pioneers of fiber art in Colombia, along with that of other international artists under the curatorship of Aluna Curatorial Collective.