REGINA SILVEIRA: “I ALWAYS UNDERSTOOD THAT EACH REPRESENTATION OF THE REAL IS PURE ARTIFICE, CODED AND CULTURALIZED”

The Brazilian artist Regina Silveira has a long career in which she tries to explore different notions of reality through her work with lights, shadows and distortions. In her five decades of artistic work, she has dealt with themes and explored media that tie in with her idea. "I choose the medium that best solves my intentions, and then I look for the skills and technical resources to make the work feasible, focusing on being a non-specialist in any medium." The artist exhibited in Europe and the American continent, much of her work is in public collections such as the Reina Sofía museum.

You’ve told an anecdote about Iberê Camargo, about a paintbrush falling on top of a moving tram in his painting classes in 1961. Would you say this was your first approach to painting? What was he like and how did he influence your artistic career?

This certainly changed the direction of my work. That gesture was a radical lesson: throwing a soft-bristled paintbrush out of the window, from a female student who was carefully painting a view of the tram terminal, left the students stunned and speechless as they saw the brush on top of a departing tram. At the time, I was already a painter, participating in art salons and assisting the artist and teacher João Fahrion in his drawing classes at the Institute of Arts, where I had graduated a year earlier. The most important thing about this story of the brush, which was at the beginning of that course at the Atelier Livre in Porto Alegre, is that Iberê then borrowed a stiff bristle brush, sat down in front of the student's canvas and passionately repainted it, masterly and with a huge amount of ink. The new painting gained autonomy and was practically a real other, in front of the reality data that it previously wanted to represent. For me, it was the first clear notion of art as abstraction and language.

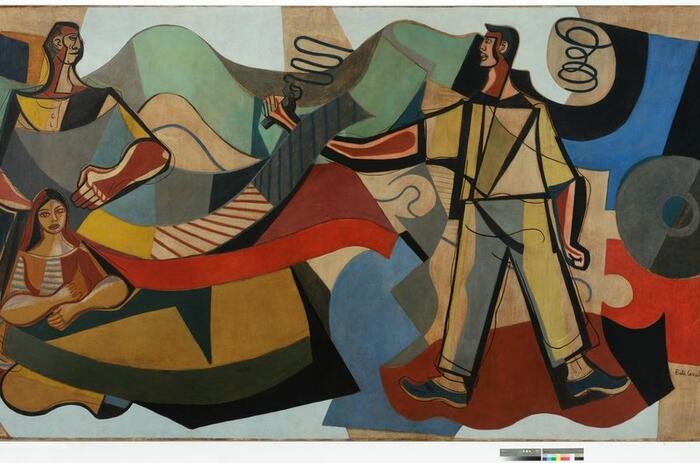

-

Memoriazul, 2005 - Impressão digital e vinil adesivo/ adhesive vinyl - Piso: 460 m2, Teto: 780 m2 - Exposição "Lumen", Palacio de Cristal, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia.Madrid, España

-

Octopus, 2014 - Vinil adesivo - - Dimensões variáveis - West Wing Biennial Courtauld Art Institute, Londres, Inglaterra

-

Refeitório, 1962 – Xilogravura - 43,5 x 66,3 cm

Within your works you deal with a number of topics, from ecological, political and existential changes. What is your point of interest when creating a work?

We are talking about six decades of intense work and a diversity of poetic provocations, in a period in which the world and art have changed so much! ... If in the 1960s I was able to reach, by great leaps, the most contemporary level of the poetics in force in those years, in the 1970s my orientations were decidedly political, supported by new means of production and circulation of images. In the 1980s and 1990s the work was more metalinguistic, focusing on the nature of images and the ways of seeing the world, its objects and their representations, sometimes made as shadows distorted by the contingencies of the point of view. After 2000 I chose more reflective and existential paths, and often, I explored the phenomenon of light, even for larger interventions that covered different architectural spaces, in museums or public areas. However, in this sequence there has always been a recurrence of themes and signs: I have a kind of vocabulary that I usually use to construct other narratives, in different contexts.

You have also used different ways of making art; from postal art, photography, engraving, painting, to urban architecture interventions. Which is the one that most represents you?

All the media interest me, and I choose them because of the degree of effectiveness they can have in putting into practice what I want to express or convey, that is, adjusted to that idea and that situation. The idea comes first, but I often come up with the medium simultaneously ...

My work has already been classified as expanded graphics - and I feel comfortable in this classification, due to the degree of freedom it offers by encompassing a diversified production like mine, with emphasis on the politics of images. I can well decide to make an engraving, a video installation, an urban projection or a tapestry. I choose the medium that best solves my intentions, and then I look for the knowledge and technical resources to make the work feasible, remaining a non-specialist in any of them. I have been working with collaborators close to my work for a long time. Digital resources have allowed me to control the scale and work remotely, in technical fields of common use.

Anyway, I have been making free use of the media, without any of them representing me.

-

Abyssal, 2010 - Vinil adesivo, paredes pintadas e filtros de luz - 10,41 x 13,57 m - Atlas Sztuki, Lodz, Polônia

-

DESTRUTURA URBANA 4, 1975 - 50 x 70 cm - Serigrafia

-

Biscoito Arte, 1976. Foto: Gerson Zanini

-

Ex Orbis, 2001 - Cerâmica sobrevidrada - 7 x 11 m - Aeroporto Salgado Filho. Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil - Foto: Eduardo Verderame

-

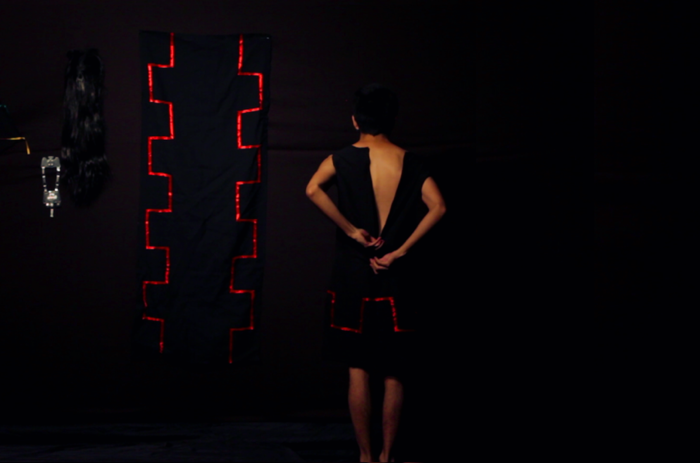

BICHO GAL, 2017 - Animação digital - Cenário do Show "Fruta Gogóia - Uma homenagem a Gal Costa" de Renato Braz e Jussara Silveira. Realização SESC - Foto: Bruna Goldberger

You are a retired professor from the Department of Visual Arts of the ECA-USP, which means that you value academic experience, but paradoxically you use art as a tool of transgression, especially in the institutional sphere. There is a very strong meeting point between these two areas, how do you explain this relationship?

As a teacher, I have always tried to maintain an experimental attitude, encouraging my students to seek their own poetry. The academic experience was undoubtedly important to me, because of the exchange that I could maintain - and continue to do so today - with the generations that have followed me.

In addition, it must be said that the institutional academic environment to which I have belonged, both at the Armando Álvares Penteado Foundation and at the ECA-USP (Escola de Comunicação e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo), was made up of several other artists who, like I, were connected to post-conceptualism in the 70's and wanted new parameters for the teaching of art. I need to add to this group Walter Zanini, Professor of Art History at FAAP and ECA USP, who also developed, since 1963, a radical program as director of the Museum of Contemporary Art at USP, often with the collaboration of his fellow artists. Zanini was also the curator of the 1981 and 1983 São Paulo Biennials, when our students were called to attend and accompany the invited artists. We all wanted to promote live teaching and, above all, in parallel with contemporary art. For many years I divided my time between the workshop and the academy, also because I was interested in helping to implement the Postgraduate in Arts in the country and define the arts in university as a research area; as important as is the Science area. Retired from my faculty duties, I was finally able to work as a full time artist.

For this year, ARCO aimed to resume artistic activities and reactivate the market, and gave prominence to Latin American art and especially to women artists. REMITENTE. Arte Latinoamericano is the section that chose 19 Latin American authors, one of which is you. First of all, how does it feel to get back into activity after all this time?

This resumption is certainly an occasion to celebrate, at least to hybridize the predominantly digital circulation of art, an inescapable circumstance in these times of global pandemic. In this cultural setting of so many interruptions and postponements, for almost two years, I never stopped working, with another dynamic in my studio and with assistants from a distance. I had at least a couple of exhibitions closed and then put into operation, with many limitations and protocols and that only now will have their catalogs published: Umbrales in Paco das Artes, in SP and Muntadas & Silveira: Diálogos - in the Vera Chaves Barcellos Foundation and at the Bolsa de Arte- Gallery, in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul.

Among the programs postponed for almost two years and which will only open to the public in August/September, is the retrospective Regina Silveira: Outros Paradoxos, a long-term exhibition, scheduled for MAC USP (Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo) with all my works that belong to the museum's collection and my participation in the 34th São Paulo Biennial. The visit and interaction with the public will naturally be limited and will be governed by the current and necessary distancing rules.

-

REGINA + MUNTADAS - Fundação Vera Chaves Barcellos, Porto Alegre, RS. Curadoria: Pablo Santa Olalla

-

Regina Silveira, Parodoxo do Santo, 1994. Foto: João Musa. Cortesia da artista e Luciana Brito Galeria

-

Umbral, 2011. Acrílico, leds, gobo de vidrio, proyección. 245 × 400 cm. Cortesia da artista e Luciana Brito Galeria

What do you think of this new approach that highlights art in Latin America and by female artists?

Long before the pandemic, heightened awareness of social inequalities and gender discrimination sparked more than just protests and demands in the arts and was able to drive some gaps in the art of women artists, who were generally assigned a secondary role or were even excluded from the art scene. It is true that, for many decades, museums and institutions selected only a few Latin artists, almost always to cover cultural stereotypes, without identifying the quality of the art produced outside the geography that was closest and most familiar to them. The feminist claims movements in art and culture only began in Brazil in the 1980s, and I am part of this history. But today I think that exclusively female exhibitions will continue to segregate if the quality of the work of these female artists is not emphasized, whether or not they have female characteristics and themes, capable of ensuring their presence in the contemporary art scene alongside other artists of any gender.

Works like Odisseia or Borders make the most out of the platform on which they are presented and have ambient and enveloping sounds to achieve complete immersion. It can be said that you are looking for representation, or an approximation to reality, through art. Have you ever found it?

I always understood that the representation of the real is pure artifice, codified and culturalized, even the most banal photographs taken. The perceived reality is more complex, it includes other dimensions and temporalities. I am more interested in codes and their conventions.

In the work Infinities (2017) - made in the virtual reality cavern of the HLRS- High Performance Computing Center, of the University of Stuttgart, and later in Odisséia (2017) and Borders (2018), made and shown later in Brazil - what I tried to do with the technical resources available to carry out work in virtual reality was to create animated simulations, where I have introduced a strong reflective dimension that could affect the participants. In Infinities and Borders the participants find themselves gradually trapped and walled in while in Odisseia they try to escape the transparent labyrinth that floats in a blue sky as their footsteps break what was left behind, preventing any return. The soundtrack fulfills the function of increasing the intensity of the experience: in Odisséia it adds the sound of broken glass and, in Borders, the sound corresponds to the rise and fall of the virtual walls that surround the subjects located within the labyrinth drawn with LEDs on the ground.

Does this have to do with "deartistification"? How would you describe this concept?

I don't remember when or who introduced this concept, but I can say that deartistification is the deliberate loss of the autograph, that is, the handprint, traditionally associated with the expression or artistry of an image or manifestation. Deartistification derives from the use of two means of industrial and technical reproducibility.

When I made the Technique do Pincel series of serigraphs, in collaboration with Julio Plaza, in the first half of the 70s or when I made the video or the different graphic versions of Arte de Desenhar, in the early 80s, the deartistification of the media and processes was surely the critical strategy directed at autography. Looking back, I can see many other applications of this concept in my work.

How do you see Brazilian art within global art? And how do you see Latin American art itself? Where is it going?

Frankly, I think that there is no Latin American art considered as a great collective, except using ethnic filters or based on culturalized stereotypes. There are many differences between our countries. In the contemporary scene, with all its mixes and displacements of cultures, I can only consider that there are artists, their poetics and their circumstances.

It is also difficult for me to predict the future paths of art made in Brazil and Latin America, or anywhere else in the world; On the creation side, with the pandemic, art itself seems to have changed, affected by the almost forced and facilitated access to digital creation and circulation, as if it had lost a bit of the thickness of its meanings, and it also shows the evident loss of data so far fundamental to the experience of art in reality: the dimensions of space and physicality.

You have presence in different parts of the world, such as the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid, and a long history. How would you like to face the next few years? I understand that you plan to start exhibiting exclusively in museums?

I have some plans ahead, immediate and for the next few years. Among the immediate ones is the aforementioned exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo, which will be open for one year, and the new work that I am building to participate in the 34th São Paulo International Biennial. Future plans include another long-term exhibition for the Site Santa Fe Museum, in New Mexico, US, with a likely subsequent tour to other institutions.

However, without restricting myself to museum exhibitions, because I intend to maintain my usual professional life, what I plan is to increase the representation of my work in museums, in Brazil and abroad. I have great respect for the role of museums in history and education: museums are public spaces, capable of housing and exhibiting works, preferably in established dialogues within their collections. It is this kind of survival that I wish for my work.