Rafael Vega: Beyond Literalism

I’ve been teaching, on and off, for about fifteen years, and frequenting art schools and university art departments as a visiting critic or the like for a good deal longer than that.

And although, when I visit graduate programs, it’s not uncommon to encounter students already embarked on careers as professional artists, at least within a local scene if not a national one, still, what counts as good, solid student work seems very different from what I think of as—without qualification—good art. Offhand, I can think of three times in those fifteen years when I’ve met a student whose work I considered fully achieved. The most recent of these encounters was with Rafael Vega, a young (yet artistically mature) painter from Puerto Rico whom I met last spring at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He has not had a one-man show anywhere and has hardly had his work shown even in group shows, but if he keeps moving in the direction he’s set out on, his will soon be a name to reckon with among lovers of contemporary painting.

All the more impressive, to my mind, is that he found this direction as recently as 2010, and that he became really clear about it only last year, yet in the short time since then he has built up a strong, very coherent body of work that nonetheless—and this is the real trick—feels open and exploratory. In other words, while each of his paintings clearly relates to the others as diverse manifestations of a single project, he is not just exhausting all the possible variants on a predefined paradigm; he is not establishing an identity by painting the same painting over and over again, or providing so many illustrations of a single idea. Instead, each painting feels like it points, from one center, toward other territories that Vega may or may not choose to explore more thoroughly as he continues to make his way across the ever-problematic, sometimes downright treacherous terrain of painting.

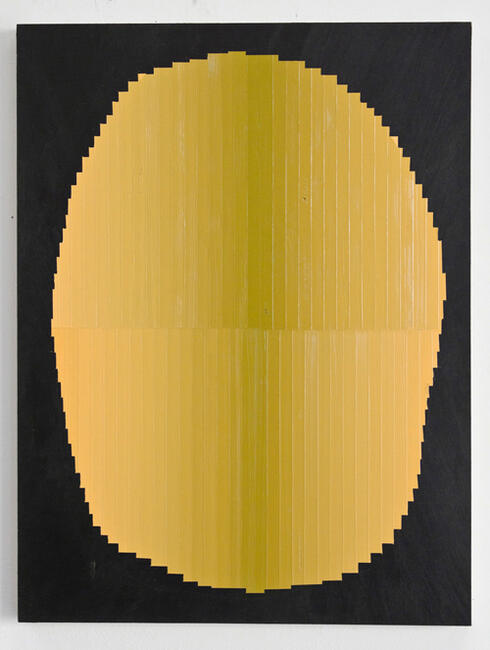

So, for instance, at first glance the most salient aspect of Vega’s work would probably be his willingness to attack the surface of the painting in the most aggressive way, scratching or carving into it, with bits of the Masonite support sometimes chipping off as a result. One might think of the way Lucio Fontana used to slash his canvases. But the difference in materials and tools—Masonite versus canvas, saw versus knife—creates a very different effect: Fontana’s gesture was simple, elegant, sexy, whereas the mark left by sawing into Masonite is rough, determined; it speaks of work more than of pleasure. In any case, while Vega could easily have made this cutting into the surface his signature gesture, he hasn’t. Maybe about two-thirds of his recent paintings employ the device, but it’s not a given. He knows that his identity as an artist is not bound up with any one particular move, and he assumes the work’s viewers are smart enough to know that too.

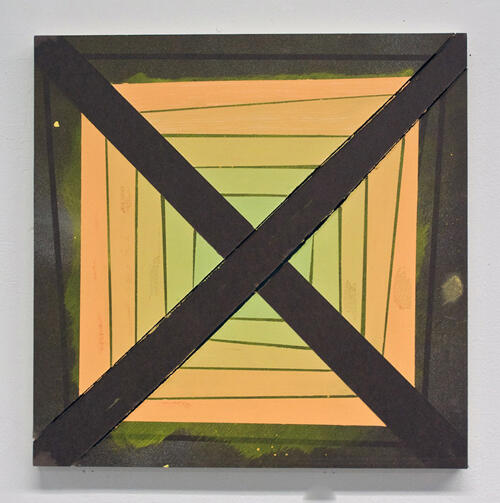

Frank Stella is another artist whose influence you might think you see in some of Vega’s paintings—that penchant for black stripes, for instance. But again, as with Fontana, the connection only highlights the differences. Scale, of course, is part of that difference—the modest size of Vega’s paintings versus Stella’s penchant for the big statement. Stella, like so many artists of his time, aspired to the definitive, the paradigmatic, one might even say, the absolute. Vega’s paintings are more in the nature of essays. They are imbued with a spirit of skepticism, a taste for the hypothetical. They are not exactly nostalgic but there is a double vision to them; they look forward and back at the same time.

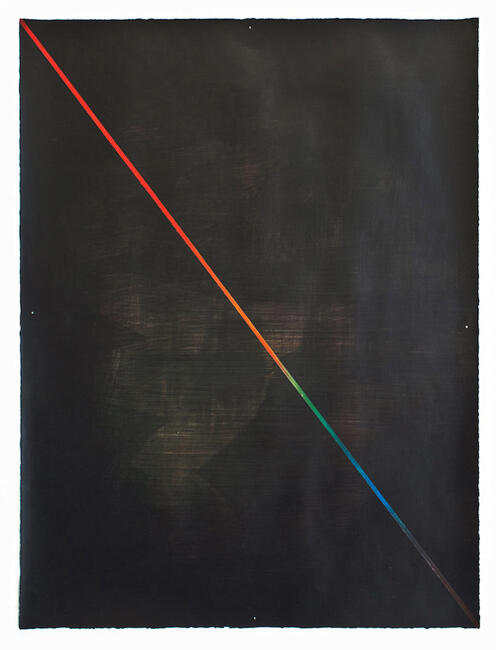

In this, Vega’s work also links up with that of a number of contemporary abstractionists, such as Tomma Abts, whose work conjures, not necessarily in any specific way but no less redolently for that, memories of various past episodes in the history of abstract art—often ones that have been somewhat sidelined by mainstream art history. It’s sometimes hard to tell how conscious these echoes are. There are moments when a painting by Vega will put me in mind of, say, something by a member of the Transcendental Painting Group in New Mexico in the 1930s, such as Raymond Jonson, or of the Madí movement in postwar Buenos Aires (Gyula Kosice, Carmelo Arden Quin)—but I doubt he has ever seen their works. Still, the Madí aspiration to achieve an art that would be “rigorous, inventive, gay and ludic” seems alive in him, if not the Transcendentals’ pursuit of a Kandinskyesque “spiritual in art,” which seems pretty distant from Vega’s concerns. He seems more a materialist, or literalist—but not polemically so, which is why he can use effects of atmosphere, of shading, that the hard-line abstractionists of the 1960s would have rejected as fostering illusionism, and therefore as eliciting a sense of something beyond the painting itself and therefore conceivably “beyond” the everyday reality we all inhabit and share.

“What you see is what you see,” declared Stella. Vega might not agree. He may be a materialist but he’s not a literalist. There is a genuine frankness to the making of his paintings, and yet they are not as self-evident as they seem. After all, this is a painter who cuts through the surface of his paintings but not to show us the wall behind it. He might be pushing paint through the cracks from the verso—which is to say that there is a hidden surface, the one that faces the wall and which the art of painting usually asks to forget. Vega asks us to remember this even though he keeps the painting’s hidden face hidden. With this work, I never feel certain where the act of painting is going to materialize next. That uncertainty is the face Vega’s art turns toward the future, the unexpected.