Claudio Girola and Poetry, the Owner of His History

A member of a family of sculptors, Claudio Girola was part of the concrete art groups in the Río de la Plata region. Like all avant-garde artists, concrete artists made use of an arsenal of pamphlets and manifestos, the first of which was the Manifiesto de cuatro jóvenes, signed precisely by Girola, jointly with Tomás Maldonado, Alfredo Hlito and Jorge Brito in 1942.

He himself has narrated that, as students, they considered the awarding of a prize at the National Salon to an artist who was also a teacher at the Prilidiano Pueyrredón National School of Fine Arts scandalous, and consequently they wrote a manifesto rebelling against the system of teaching art and the system for obtaining artistic recognition. Although the four students expected to have support from their fellow students, their only achievement was a demand from the director of the institution requiring they ratify or rectify “the harsh remarks contained in the pamphlet”, after which they decided to ratify their words and abandon their academic training. Recalling the event, Girola celebrated having been born to “artistic life through passion, the verb, non-conformist work, and the watchfulness to keep options to concerns open and not betray them.”

In the summer of 1944, the journal Arturo. Revista de artes abstractas was published, and that nucleus of young people gave rise to the concrete art groups: the Madí group and the Asociación de Arte Concreto Invención – AACI (Concrete-Invention Art Association). While Girola formed part of the latter, both groups proposed an art based on pure “invention”, which had its point of departure in simple forms painted in planar colors, either composing coplanar structures displayed directly on the wall or paintings with trimmed frames whose edges echoed the geometric shapes they contained. During that period, Girola’s sculptures dealt with form/space relationships and directional issues.

Once the AACI was dissolved, the young artists continued to seek different forms of organization and alliances with the aim of consolidating and disseminating the still controversial abstract language. In that context, Girola participated in the collective brought together by Aldo Pellegrini which, as of 1952, was known as Grupo de Artistas Modernos de la Argentina – GAMA (Group of Modern Artists of Argentina - GAMA), composed of some artists who complied with the concrete program and others who preferred a freer abstraction.

At that time, the Chilean architects, too, were promoting a transformation of their curricula. The Catholic University of Chile in Santiago convened Josef Albers as Chair of its Visual Arts course, while the reformists group at the Catholic University in Valparaíso (UCV) included architect Alberto Cruz Covarrubias and the Argentine poet Godofredo Iommi. In the framework of this modernization process, in 1952 the UCV organized the “First Exhibition of Concrete Art”, which featured paintings by Hlito and Maldonado and sculptures by Enio Iommi and Girola, in Viña del Mar and Santiago de Chile.

After this first contact, Girola made frequent incursions into the Chilean cultural field, until in 1956 he accepted an invitation to join the staff of the School of Architecture in the Catholic University at Valparaíso, since he shared the teaching proposal which contemplated arousing the students’ interest in architecture through poetry (understanding the term ‘poetry’ as “a ‘making’ that creates something which did not previously exist”, as it was considered in Ancient Greece). He was initially appointed Professor of Visual Arts, and he was later a founder member of the University’s School of Architecture. Having settled definitively in Valparaíso, it was there that he conceived the bulk of his sculptural oeuvre under that same poetic conception.

In a retrospective analysis of his production in 1991, Girola pointed out eight specific moments in his sculptural work. However, he explained that those moments should not be understood as stages but as high points of interest around which his aesthetic concerns revolved throughout time. He situated the first moment in the work on volume-mass during the stage of learning and experimentation. That initial interest progressively relinquished its predominance, which was transferred to three-dimensional planar shapes that served as support for both the folded planes and the triangulations − the result of working with cut and folded metal − and for the concrete sculptures, made in gesso or in lacquered or natural wood.

Then the directional became dominant, since the synthesis of the forms tended to represent volumes only on the basis of their edges and directions. However, the processes of change moved on towards an abstraction and a geometricization which began to include the fracturing of the volume and the integration of the bases.

Although the questioning of the base or pedestal runs through the history of sculpture, Girola radicalized the approach and proposed the displacement of the sculpture piece from the upper section of the base on which it had always been placed: the result was a new configuration which integrated this support structure.

In other projects, he acknowledged his intention to “build a void” and even his will to put “dispersion” in operation.[1] These were fields to be explored which, like the 1980s’ Dispersas, questioned tradition by multiplying the points of support of an oeuvre which, in any case, placed the emphasis on volume and the line.

All these developments in the three-dimensional space were accompanied by work on the paper support. His drawings, paintings and collages recorded the different moments in his sculptural practice and opened up freely to both the exploration of materials and textures and the new relationships between color and form.

Among the experiences he developed in the University workshops, in 1965 he was part of the first Travesía de Amereida , whose itinerary attempted to cover the distance between Tierra del Fuego and Santa Cruz de la Sierra in Bolivia. That first poetic journey was carried out together with American and European designers, sculptors, poets, painters and architects. Since the 1980s, last-year students in the Catholic University at Valparaíso’s School of Architecture go on a journey in which they execute specific works related to their workshops at a given place, with the aim of working on the sensitive perception of the environment.

As of 1973, Girola also served as a professor in the careers of Graphic Design and Industrial Design, and in 1976 he was one of the founders of the Ciudad Abierta (Open City) in Ritoque, where he left several works, among them, one of his most original proposals − “El Pozo” − a space which viewers can walk through and which appeals to all their senses. When moving along this crevice that descends below the level of the opencast terrain, visitors can perceive the narrowness of the space, the texture of the quarry, and the passage through the increasingly intense shadows to full daylight, experiences which evoke an intimate introspection.

When crossing the high Andes Mountains from Argentina to Chile, the sea opens up onto an immeasurable horizon. If “invention” had guided Girola’s work in Argentina, that boundless horizon seems to have set the course for his searches during his Chilean stage. From that moment on, freedom and poetry amalgamated in the thinking and the visual oeuvre of this artist who is currently being awarded the place he deserves in the narratives of Latin American art.

* CRISTINA ROSSI. Holds a Ph.D. in Art History and Theory (UBA), Professor and Researcher of the course on “History of American Art II” (UBA) and on “Curatorial Narratives” (UNTREF). She has served as a researcher on different national and international projects, among them, Documents of 20th Century Latin American and Latino Art (ICAA), Museum of Fine Art Houston. She is the author of Jóvenes y modernos de los años 50 (2012), Víctor Magariños D. Presencias reales (2011); the compiler of Antonio Berni. Lecturas en tiempo presente (2010), and co-author of La abstracción en la argentina siglos XX y XXI (2011), Palabra de artista. Textos sobre arte argentino 1961-1981 (2010) and Arte Argentino y Latinoamericano del siglo XX; sus interrelaciones (2003). She is an independent curator and a member of CAIA, AACA-AICA.

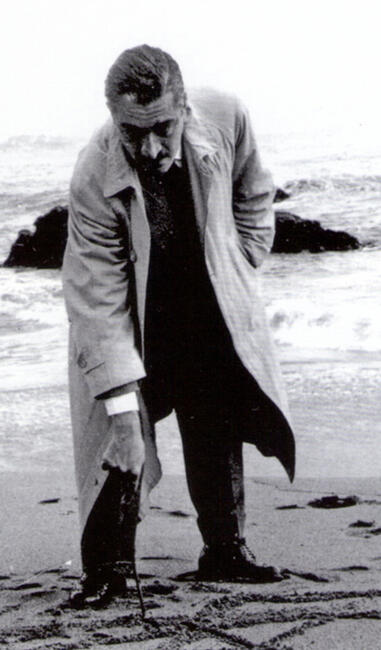

CLAUDIO GIROLA (Rosario, 1923 – Valparaíso, 1994)

Girola had his first artistic training at his father, Santiago Girola’s workshop in Rosario. He then studied drawing with painter Pedro Fornells and, in Buenos Aires, he enrolled in the National School of Fine Arts, where he was a pupil of the sculptor Antonio Sibellino. He was part of the concrete avant-garde movement together with his brother Enio Iommi and friends. In the mid-1950s he settled in Chile, where he worked at the Catholic University in Valparaíso.

In 1963 he obtained the Braque Award and traveled to Paris, where he took part in the Phal è nes or poetic acts carried out by Godofredo Iommi (his uncle) and participated in the Revue de Poésie. Among his countless exhibitions, special mention may be made of Claudio Girola. Tres momentos de Arte, Invención y Travesía 1923-94 (2007), which was accompanied by a book that included the catalogue raisonné of the work surveyed until that moment.

Inclined towards aesthetic reflection, Girola left his thoughts in manuscripts and editorial projects such as O Pureté!, Pureté!, Rimbaud (1981) and Cuatro Talleres de América en 197 9 (1982). After his early choice to work in Chilean territory, he continued to do so until his demise, in 1994.

[1] Cf. Claudio Girola, Retrospective Exhibition “Claudio Girola Escultura y Travesía 1940-1991”, Parque de las Esculturas, Santiago de Chile, 1991.