Antonia Guzmán

Americas Collection , Miami

To a great extent, the safeguard for attempting the use of a lan- guage that represents the feminine has been the aggressiveness of proposals which, due to their strong content of emotional or social violence, cannot be considered “weak”. From Louise Bourgeois to Tracey Emin, the immersion in private matters and in typical gender issues whether it be the pathological mother-daughter relationship or the traces of biological female processes, the “confidence”, acquires a harshness that renders it invulnerable in the context of the establishment.

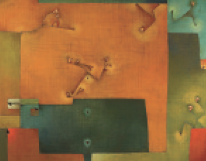

In the case of Antonia Guzmán, what is transgressive and risky but also defensible is the option in favor of a subtle language, in which the tensions of affective bonds and the art- everyday life relationship are translated onto the construction of apparently placid pictorial surfaces inhabited by characters reduced to basic traits, and to the artist’s action with elemen- tary symbolic figures. The exhibition Lazos de Amor, at The Americas Collection in Miami, reflected the way in which Guzmán assumes herself as a woman artist, addressing couple issues or motherhood through an oeuvre that transforms the remote memory of certain pre-Columbian geometric iconographies present in the experimentations of the School of the South, fuses an abstract and figurative representation of the world, and uses symbolic codes that the viewer identifies as an emotional alphabet: the black or violet triangle is linked to sex and to the heart, and functions as the sign of desire. It features a narrative of the emotional world, attraction rejection events; explorations of the solitary identity or of the otherness play that takes place in vast geometric spaces. The dimension of her houses is cosmic, and the characters may gravitate towards one another when they draw near, although the image of the figure meditating at a sort of window sill or on a roof top, seated, in any case, in a space that is on the border between the person- al habitat and the world, the inside and the outside, is recurring. In fact, spatial compositions imply the notion of a transit linked to the dynamics of relationships.

In the representation of bonds which also shows certain similitude with Joan Miró the reference Guzmán invokes is equally transgressive of canons: the “real” art of autistic or deaf children to whom she has taught art, but who have ended up by teaching her the power of the simplification of forms charged with a strong emotional content and freed from both superfluous details and logical representation rules. At a later stage, she worked with the notion of residues, aware of the fact that all painting is a palimpsest of earlier works as much as of layers of one’s own life. Artistic and personal memories accu- mulate on the surface of hand-made papers or cotton fabric onto which she applies layers of watercolor or acrylics to scrape areas that rescue the traces of earlier colors and juxta- pose new colors. The notion of the invisible fabric that supports the work is clear in this universe where the characters perform plays of forces in tension, vital dramas rendered more subtle through the simplification of forms. Spatial placement gives shape to an alternative code, a personal alphabet of affective states: when they are confined within architectonic interiors (a metaphor for isolation), they are more rigid than when they float in the color fields. The inclusion of poetic texts in the works exhibited reinforces the presence of an affective content that eludes the farcical or the recourse to the absurd. The lit- eral meaning of phrases such as “Do not go yet”, or “I hold you”, prepares the spectator for an immersion without violence into the depths of a universe which does not evade pronounc- ing the word Postmodernism feared the most: love.