The Círculo de Bellas Artes Of Madrid Welcomes the Work of the Photographer Horacio Coppola

Pioneer of the Vanguard in Argentina

With the collaboration of the Jorge Mara-La Ruche gallery and the AECID, el Círculo de Bellas Artes (The Circle of Fine Arts) of Madrid welcomes to the Sala Picasso the work of Horacio Coppola, pioneer of photography of the Argentinean vanguard and an artist who has made one of the best portraits of Buenos Aires. Coppola was born there in 1906, and he still lives there. However, the exhibit that will be available at the CAB does not include, amongst the more than a hundred pieces it owns, any picture of the portal capital.

Ello es así porque Horacio Copola. Los viajes, (This is so, because Horacio Coppola. The travels), an exposition organized by the Circulo de Bellas Artes in cooperation of the Galería Jorge Mara-La Ruche of Buenos Aires, and with the support of the Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo (AECID) (Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development), is centered in the initial production of the photographer, product more than anything, of his years of formation in Europe during the early 30s of the 20th century. The history of Horacio Coppola is full of fortunate coincidences that, in retrospect, form a completely coherent trajectory, even if while they took place they were not part of a strategically designed plan.

Born from an Italian family in which art and culture were very present, Coppola begins his formation as a self-taught photographer during the late 20s. During this period he’s still an amateur. He studies law without much interest, forms part of the executive board of the Cine Club in Buenos Aires; he assists conferences by European intellectuals (Ortega y Gasset, Le Corbusier…) who pass by Argentina, he is the director of the magazine Clave de Sol… The only clear thing during these years was his interest for art, specially film and photography.

In 1930 he travels to Europe for the first time and visits Spain, France, Italy and Germany. On his return he has a lay-over in Brazil. In 1931, the magazine Sur begins to publish some of his pictures, but he is still fundamentally interested in film. Things begin to change the year after.

In 1932 he returns to Argentina to study photography at the University of Marburg. The intention was for him to specialize in the field and develop a critical language on this artistic technique. However, once he arrives to a Germany where the rise of Nazis is becoming unstoppable, he finds that the Department of Photography at the University of Marburg has been closed. He ends up taking photography classes at

Walter Peterhans in the new Bauhaus of Berlin. There he meets his future wife, Grete Stern, and moves definitely towards photography.

In 1935, both go back to Buenos Aires. As soon as they are back, the H. Coppola and G. Stern photography exposition section is organized in the magazine Sur, and is received as the “first modern photography exposition in Argentina”. Because of this, the Municipality of Buenos Aires commissions Coppola to realize an extensive photography piece of the capital, which would in turn result in the book

Buenos Aires 1936. Visión fotográfica.

What was meant to be a temporary stay in his city of birth ends up being prolonged by various successive commissions. In the end, the stay becomes definite, closing the circle of fortunate coincidences that made Coppola the photographer of Buenos Aires.

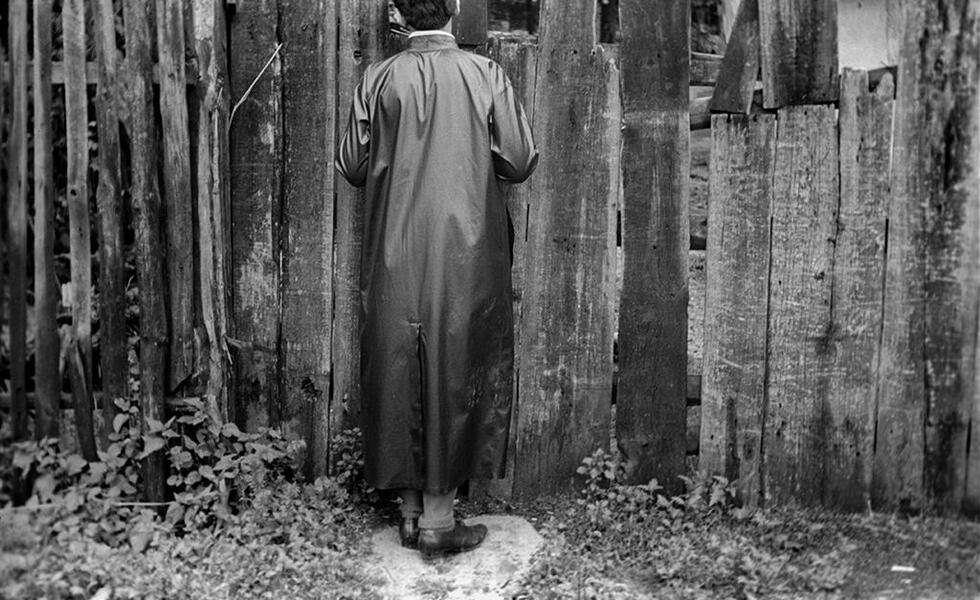

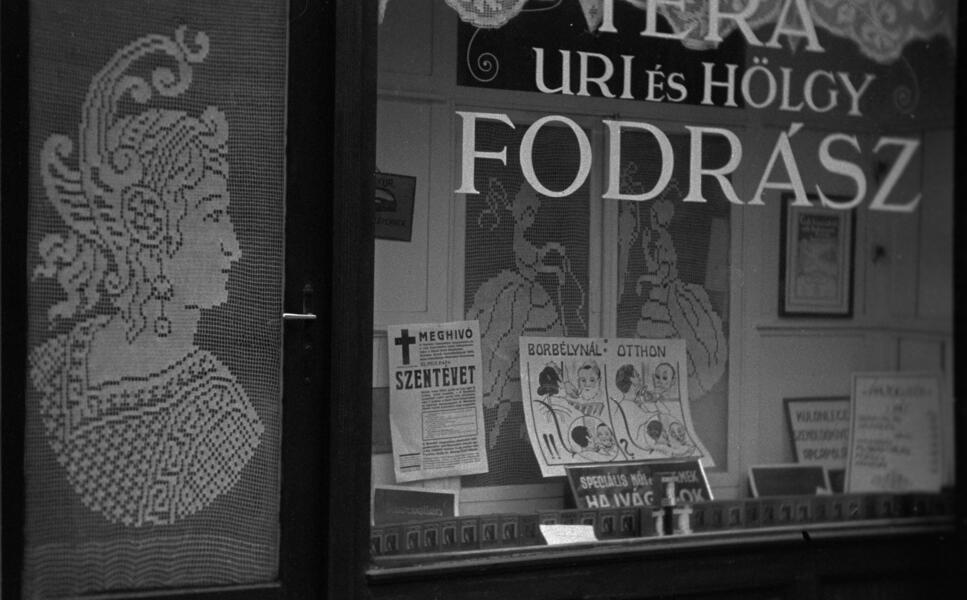

The pictures that are part of the exhibit are the product of Coppola’s stay in Berlin, and his trips to Budapest (1933), Paris (1934), London (1935) and Brazil (1931 y 1945). In them, a developing photograph leaves behind his trademark obsessions and his style. It is clear, for instance, just like Natalia Brizuela points out in the excellent catalog of the exposition, “if we had to identify a recurring object in the eyes of Coppola, it would be, without a doubt, the city”.

The rigorous labor that photography requires is also made clear. Coppola does not photograph randomly. There is nothing in his pictures of the “decisive instance” of Cartier-Bresson. The Argentinean consciously studied objects and subjects before proceeding to take his pictures. He looks for unusual visual angles –top down and bottom up- and perspectives carefully chosen that bring to mind Moholy-Nagy, who shared as many similarities as dissimilarities with Coppola (Coppola has never admitted the manipulation and montage of his pictures like the Hungarian master did).

“He is a careful reader”, Brizuela assures, and adds “This constitutes one of his biggest debts to the teachings of the Bauhaus. Photography is construction and it is careful observation…(which leads) to the radical transfiguration of the referent, to the rediscovery of everyday things, to the feeling of nostalgia for the real”. This transformation of everyday things can be observed in all of Coppola’s photographs, even in the apparently common and simple. It is a transformation that is not evident a lot of the times, and which is perceived more subliminally than consciously, but that forces us to always look with new eyes, with the amount of attention we have never paid before. As for the series of pictures that form the exposition, the ones from Berlin show us Coppola’s first raids into matters of social and political nature, a line of action that deepens in Budapest, the pictures of Paris, and also, the first focus on graffiti, an interest that is shared with modern photography: that is the case of Brassaï (to whom, just like the quoted Moholy-Nagy, the Círculo de Bellas Artes dedicated a recent exposition).

In London, Coppola’s pictures gain an unusual vivacity. He photographs urban agitation and the reality of the excluded, choosing images of social abandonment: homeless people, street vendors and beggars…ultimately, a photographical social critique of London. The pictures from Brazil combines a little of everything: the interest for composition and the aesthetic of the picture in itself, as well as a portrait of social life.

Along with the photographs, the exhibition displays the four most important films of Coppola’s brief career as a director. Sueño (1933), is an expressionist experiment that was never continued. In 1935 he films Un muelle en el Sena, in Paris, and, in London, Un domingo en Hampstead Heath, both of a strong documental character.

Subsequently, in Buenos Aires Así nació el Obelisco (1936) would come out, a brief, almost advertising piece about the construction of the monument that presides the cross between the avenues 9 de julio and Corrientes of the capital.

Coppola ended up focusing definitely in photography. We can only speculate about how his film career would have turned out if it had been prolonged, but there can be no doubt that, when we contemplate his photography, we are in front of one of the great Latin American masters of the discipline.