Fernando de Szyszlo has cressed over the threshold of myste

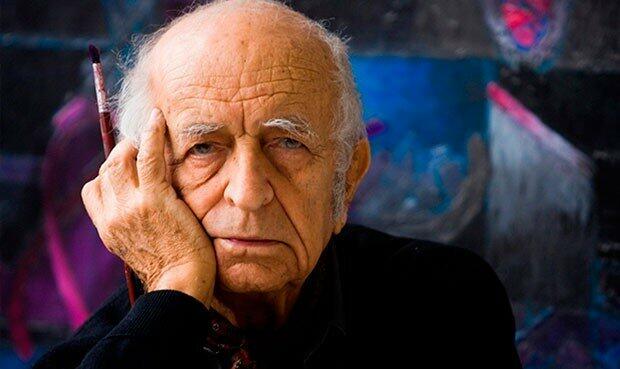

Fernando de Szyszlo (Peru, 1925–2017) has crossed over the threshold of mystery that his paintings so often suggested. Perhaps more than any other master of Latin American modern art, his work brought together the lessons of a lyrical abstraction that never eschewed earthly forms, on the one hand, and the heritage of pre-Hispanic architecture and of its mythical universe, on the other.

Along with his wife, Liliana de Szyszlo, he left this world at the age of ninety-two, still lucid. Indeed, he was planning a public conversation with journalist Andrés Openheimer to be held on October 12 at Durban Segnini Gallery in Miami, where his last show is still on exhibit. Its title, Szyszlo, evidences the power of his very name. That was also the title of a retrospective organized by the Museo de Arte de Lima, MALÍ, in 2011, a tribute to “one of the most representative and well-known artists in the country.”

The mere mention of the name, in the case of that show, sufficed to conjure up a universe enlightened by the artist’s ability to “convey, in a contemporary language that holds the essence of timelessness, traces of an age-old iconography whose origin lies in “our Americas”—to use José Martí’s term—and in its mythology.” That was how the text entitled El gran conector de mundos, published on the occasion of his 2011 exhibition Sombras y sueños, described the artist. That show was the second in a series of five exhibitions organized by the aforementioned gallery. The first, Habitación N.23, was held in1995. The title of that exhibition looked to a verse by Enrique Molina that is, today, even more pertinent: “I disavow my origin and my name until I lie among the most beautiful heavenly rubble.”

The conversation that was to take place on October 9, just three days after his unexpected departure, would have addressed his artist’s book, whose beautiful title, La vida sin dueño [Life with no Master], sums up the artist’s being. Mario Vargas Llosa wrote a sentence that captures both those memories and the entire life of a man born to a Polish father who spoke fourteen languages and a Peruvian mother who had inherited a wonderful library that saw the young artist through a asthmatic childhood: “An air of freedom runs through all these pages as they conjure his life with no euphemism, affront, or censorship, but rather with candor, intelligence, and clarity in equal measure.”

Only someone like him—heir to the hallucinations of Surrealist friends like Breton and to the shadows of César Vallejo, to name just a few of his many literary influences—would have been capable of so perfectly conveying in painting the inspiration that moved him in the heights of Machu Pichu, “The visible encounter between the sacred and physical matter.” This man and his visions were able to reinvent precise geographic locations with a mythical dimension that went beyond past defeats and the frustrated dreams of modernity. In his art, he acted as the great binder of worlds, bringing together the pre-history of his continent and twentieth-century avant-garde movements in a battle waged solely to create, always as if for the first time, awe-inspiring work. An apt farewell is a passage from Rilke’s The Deuino Elegies, which he loved so very much “an almost deified youth suddenly quitted forever, emptiness first felt the vibration that now charms us and comforts and helps?”