Esteban Lisa

Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid - Museo de Santa Cruz, Toledo

A new gold standard has been set with the opening of Esteban Lisa: Retornos, Toledo, 1895 / Buenos Aries, 1983 at the Biblioteca Nacional de España. The retrospective featured 149 works of art beginning with the artist's early abstract experiments in oil on cardboard rendered in a cubist-inspired style from 1930 to 1940. (Ill. 1)

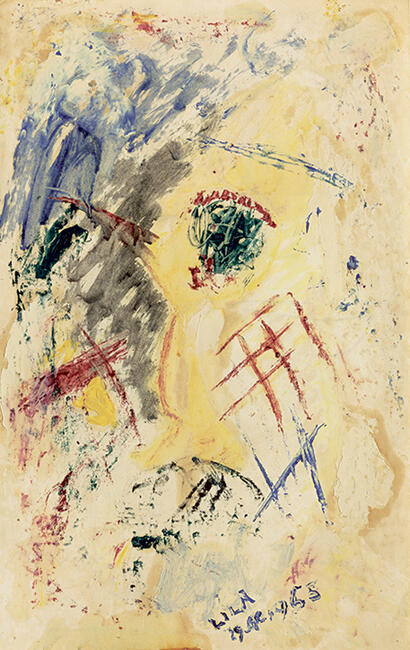

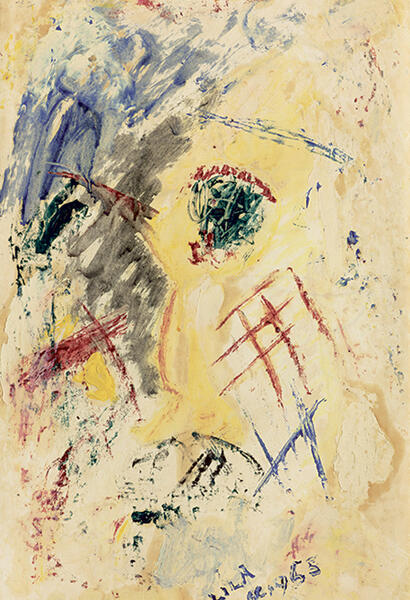

A few of the earliest works datable 1930 still reference empirical reality as observed in landscapes, several of those descriptively titled as such by critics writing posthumously on the artist. Most of Lisa’s work from the early years was painted without specific references to a recognizable natural scene. From approximately 1935 to 1940, Lisa began to introduce brighter colors, gestural markings, and a greater sense of pictorial play. (Ill. 2) Interestingly, some of the works seem to nod to the generalized directions in Robert Delauney’s abstract compositions.

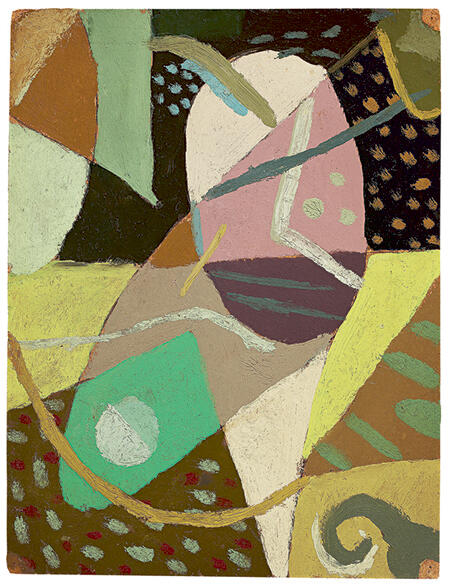

Lisa’s work from 1940 to 1954 shows an extraordinary formal leap from the earlier multi-angled, overlapping geometric forms to a vibrant, painterly organic abstraction. (Ill. 3) From 1940 through 1952, Lisa titled his works Compositions, and in 1953 he referred to them as Playing with Lines and Colors. With those paintings, Lisa hit his stride and maintained it until he stopped painting in 1978 when his wife became ill. Each small-scale work features lines crossing, darting, and overlapping, each imbued with a sense of musicality, even dance: one feels as if the lines, dots, dabs, irregular shapes, and squishes of paint will take flight beyond the limits of the paper’s edges. (Ill. 4) Some of these may bring to mind similar formal expressions in Joan Mitchell’s pastels on paper from the mid-1970s.

Not only did Lisa avoid the geometric morphology of pioneering Argentine painters associated with Arte Madi, Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención, and Perceptismo in the 1940s and 1950s, but he determinedly evolved a multifaceted practice that may be characterized as idiosyncratic.

Lisa painted every day in the privacy of his home and chose not to

exhibit his prolific production during his lifetime (he died in 1983). Painting remained a private passion, need, and endeavor that he kept apart from the commercial world—as small as it was in Buenos Aires. Supporting himself as a full-time librarian in the central post office, he taught art to young students in night classes and to adults privately. He established two schools: the Four Dimensions Modern Art School of Buenos Aires in 1955 and the Institute for Research of the Theory of Cosmovision in 1966.

Lisa was committed to a lifetime of learning and formed a personal library that included thousands of books on the humanities (art, art history, dance, music, and theater), science, pedagogy, mathematics, astrology, ethics, Catholicism, Eastern and non-Christian religions, psychology, and philosophy.

As an artist, he believed that painting and drawing were creative as well as

spiritual acts that marked one’s very being. He held that abstraction communicated his views of a cosmovision. As often cited in the critical writings as well as in a quote in the exhibition installation, Lisa said: “In a space of 10 by 10 cm. you can introduce the totality of the universe. It is not size that makes the universe, nor is it the things outside of oneself; it is the internal state that makes for the immensity of things.” (Ill. 5)

The installation of the exhibition at the Biblioteca Nacional de España was extremely impressive for the breadth and detail of the work selected, its impeccable hanging, and its formal and thematic groupings. The signage provided viewers the biographical, theoretical, and contextual background needed to understand the artist's diverse practice. Strategically placed vitrines showcased fourteen books Lisa had written; catalogues from all the artist’s exhibitions beginning with the first statement by Martín Blazko in 1987; essays on him; and unframed works from the 1930s through the 1960s. A few vitrines featured excellent examples of small, unframed works from the fifties and sixties that Lisa executed one after the other. The point was to exemplify the serial cohesion, the internal dynamics of the work as it progressed on a daily basis as if he conceived them as a diary of images. (Ill. 6) The installation also included a video, now on YouTube, in which four of Lisa’s closest students (including Isaac Zylberberg and Horacio Bestani who started the Foundation Lisa) discussed their late master’s ideas, practice, and pedagogical philosophy.

The 294-page bilingual catalogue contains five essays (including those by Stéfan Leclercq, Artur Ramon, and Julia P. Herzberg,), illustrations of each work, and a list of works with provenances, critical references, and exhibition histories. The essay by the curator, Miguel Cereceda, casts scholarly and innovative views on Lisa's artistic accomplishments, philosophical interests, pedagogical activities, and artistic contributions. While building on former research, Cereceda challenges a number of chronological developments, philosophical premises, and artistic sources that have informed Lisa studies over the past sixteen years. A section on biographical details by the historian Julio Sánchez Gil sheds new light on the personal and professional life of Lisa, who was born in 1895 in a small village near Toledo, Spain, and emigrated at the age of fifteen to Buenos Aires, where he lived for the rest of his life. Sánchez conducted mole-like research in both countries, scouting documents to confirm dates; reading unpublished family letters and interviewing people for a better understanding of the artist's enigmatic personality. His work has begun to fill in a lacuna that has existed to date. The catalogue is an important contribution for future researchers, art enthusiasts, and collectors.

As the artist's work becomes better known inside as well as outside of his adopted country, it will expand the canons of Latin American abstract art by advancing an understanding and appreciation of a very talented artist whose lyrical abstract paintings from the late forties through the late sixties have contributed significantly to the streams of artistic creativity in the western hemisphere.

-

29/08/1965

29/08/1965

Oil on paper/ Óleo sobre papel - 35 x 22 cm.

(back) – preparatory drawing on pencil signed and dated 17/08/1965

(reverso) - dibujo preparatorio a lápiz firmado y fechado 17/08/1965

Fundación Esteban Lisa, Buenos Aires, Argentina / Photograph courtesy of / Fotografía cortesía de Fundación Esteban Lisa

-

[8 from Jorge Virgili]

[8 from Jorge Virgili]

10/05/1935

Oil on cardboard/ Óleo sobre carton/30 x 2 cm.

-

Ill. 2 / Il. 2 [15 from Jorge Virgili]

Ill. 2 / Il. 2 [15 from Jorge Virgili]

Oil on cardboard/ Óleo sobre carton/ 30 x 23 cm.

(reverso)/ back(double sided) (cuadro de dos caras) /