_Drawing, out of control_

Ciudad de La Laguna, Tenerife.

The exhibition El Dibujo Fuera de Sí: Tríptico de Venezuela (1970-2014) will be held from July 11 through September 21 at the Sala de Arte of Instituto de Canarias Cabrera Pinto, La Laguna, Tenerife (Spain).

Resorting to the drawings of three distinguished Venezuelan artists – Alejandro Otero, Andrés Michelena and Magdalena Fernández – Roc Laseca, a Canarian curator based in Miami, proposes a reflection on “the future” of the death of modernity and its funerals in Latin American culture.

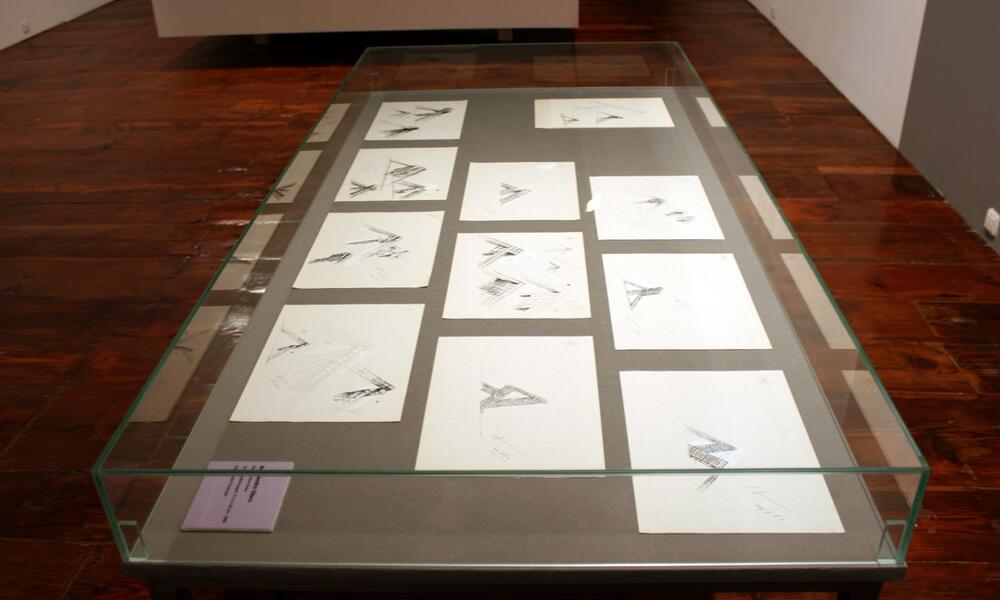

The drawings of Alejandro Otero, a classic of the Venezuelan avant-garde movement, are the only ones actually made within the temporal limits of modernity. Even in its informalist origins, Otero’s work was always governed by a drawing which imposed structure upon matter along the lines of his admired Cézanne and his Cubist followers. In the 1950s, the line finally prevailed, with no resistance from matter, in a geometric abstraction in tune with a sensitivity very widely spread in Latin America. Already in the 1970s, that trust in cultural rationality and modernization acquired monumental form in large geometric sculptures in which the haughty autonomy of pictorial modernism converged with the constructive arrogance following the tradition of Le Corbusier. Quite logically, Otero´s drawing of this time is instrumental; it shows the carefree assuredness of the engineer who designs a functional structure.

That functionality, which could have been perceived as heir to the instrumental rationality that inaugurated Western hegemony in the dawn of the bourgeois society, was however understood in the Latin American context as a resistance to the exoticism which that same colonialist world view expected from the “peripheries”.

The interest in the unwillingness of young generations to dispense with drawing may perhaps reside in this paradox. In the midst of full exaltation of a documental and anthropological art, realistic and heteronomous, of relationships, events and situations, incompatible with the foresighted rationality of drawing, Magdalena Fernández seems to want –literally- to introduce the regular nature of design in an environment, now already postmodern, which Bauman has insisted in characterizing for its “liquidity”. Through a poetically simple procedure, which satirizes technology, she makes “video-like” drawings which allow her to subject geometry to some fluctuations in which, nevertheless, a less rigid than choreographic desire for regularity persists, as if reason did not wish to take part, either, in a revolution in which dancing was not allowed. Here, the hypnotic formalism of modernism comes together with the randomness of the event, to take importance away from a nonetheless persistent desire for order and containment, which contrasts intensely with the expectation of “anthropologic authenticity” that the metropolis continues to encourage regarding Latin American art.

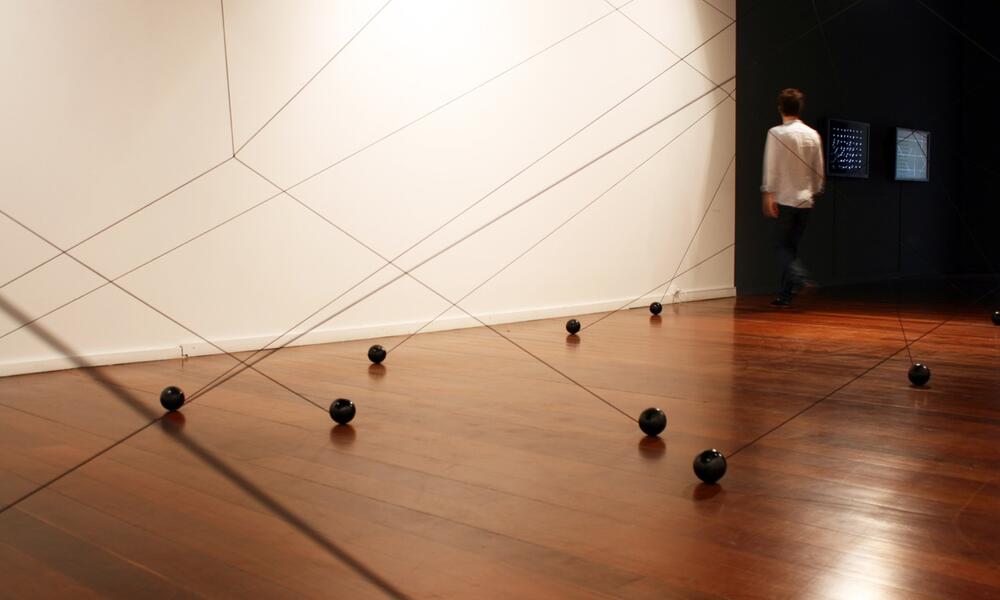

Michelena, in turn, adds representation and language to his well known ironies on the eminently linguistic and signic nature of the pretended modernistic resistance to sense, a number of poetical strokeless drawings produced by some devices reminiscent of kineticism (with the same poetic “low tech” with which Magdalena Fernández approaches the “new technologies”), now moved by the encouragement of the viewer, who is forced to get closer to the drawing to verify how the gaze alters that which has been seen. The faint shadows “draw” on the paper some trembling houses which seem to wish to timidly remind us of the possibility to continue inhabiting the metaphor, harassed today by an obsessive need that the Word become flesh, or to continue hosting the idea, already devoid of the slightest trace of arrogance or idealism.

Laseca’s project –produced in collaboration with The Chill Concept, Colección Capriles de Brillembourg and ArtsConnection– enters into an active and dialectic dialogue with its location in the Canary Islands (a European territory situated in Africa with clear Latin American vocation), not only because of the contrast between its private funding and the absolute paralysis that Spanish culture, traditionally dependant on now exhausted public funds, is experiencing; but also because of its aesthetic and ethical links with an autochthonous sensitivity that I like to term ‘Calvinist’, not in reference to the reformist theologian (in spite of their shared containment and sobriety), but to Italo Calvino who, in his Six Memos for the Next Millennium, linked consistency, exactitude and visibility with lightness and multiplicity.