Rubén Torres Llorca

Praxis International Art New York

So Quiet in Here was a memorable installation by Rubén Torres Llorca at El Museo del Barrio in New York in 1998. It was a parodic recreation of a historical account dating from Belgium’s colonial era that involved the Geographic Society of Brussels and an African family that was living inside the zoo in Brussels for a period of time before they quietly disappeared. In that fictive space, blackboards with handwritten texts in pastel, drawings, and sculptural objects addressed cultural dis- placement, historical identities, and transcultural misgivings. Torres Llorca’s most recent exhibition was equally notable for its conflation of images—painted, drawn, and photographed, objects, both handcrafted and found—and apocryphal texts based on diverse literary sources, which continue to inspire his artistic practice.

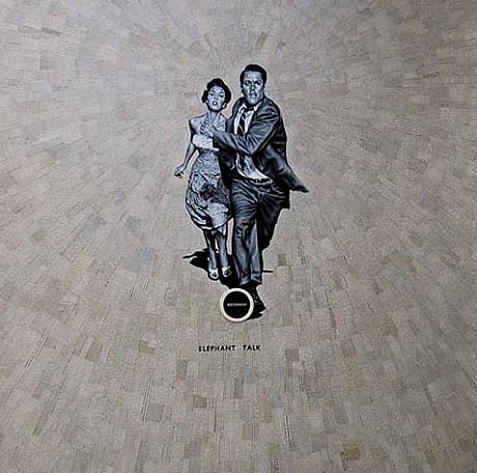

Three works comprising the gallery installation offer a glimpse of the unexpected turns of Torres Llorca’s hand and mind. A miniature male figure with a female doll’s wig in Ella cantaba boleros (She Sang Boleros) is an expressive combination of body language, text, and romantic nostalgia. [Illustration] The sculpture references the legendary character Estela in Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s Tres Tristes Tigres (Three Trapped Tigers) (1965), an animated account of nightlife in Cuban cabarets. Estela, the bolero singer, weaves a tale of a man who gives himself up (rendir) to the woman he loves. The diminu- tive sculpture evokes the spirit of love songs, a genre that has historically marked time and place in Havana life.

The wall text accompanying Ella cantaba boleros is attributed to the illustrious Spanish writer Ramón Gómez de la Serna, known for his humorous one-line poems. Torres Llorca’s upside-down version of the Brothers Grimm dialogue gives a new twist to the pin-up narrative. “The big, bad wolf asked: Little girl, why are you so innocent? And Little Red Riding Hood replied: The better to eat you.” (El lobo feroz pregunto: Niña, ¿porque eres tan inocente? Y caperucita roja contesto: Para comerte mejor.)

Another sociologically oriented work is Blessed Is the Artist Who Has Everything for Sale. The painting features an image of a Gil Evergreen pin-up girl from the 1940s who sways her hip, lifts her skirt, and reveals her legs. Even though her eyes are covered with a black strip, she is instantly recognizable, culturally acceptable, and easily purchasable. Her presence reminds us of the long history of the sexualized woman in pop- ular culture. The text, attributed to Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland, reads: The only consistency you can expect from me is that I did and I will do everything possible to disappoint you. In a humorously, critical feminist mode, the text upends the expectations of the pin-up’s come on!

Un lugar acogedor al que no podemos entrar (An inviting place which we cannot enter) (2008) features sculptures of a rabbit and a pig, who, side-by-side, stare at a miniature-sized house, as if frozen in time. The handwritten wall text complicates the already strange narrative, prompting a range of visual as well as literary interpre- tations. Attributed to Patricia

Highsmith, an American writer known for her mystery/thriller novels (her Strangers on a Train, for example, was adapted for film by Alfred Hitchcock), the text reads: Hansel and Gretel were abandoned by their par- ents. End of story.

Torres Lorca’s stories, construct- ed in spaces that resound with quietness and impending drama, are always disquieting. It was good to see his recent work again here, outside of Miami where he lives and works.