Guillermo Kuitca | Noesis of The World

Kuitca’s work leads us to reflect on the power of visual signs and of their evocative influence. For Kuitca, painting is a “noesis“, or an intentional act of perceiving or judging, a practice of phenomenologic interpretation and of consciousness of the world, in a Husserlian sense; an act of perception of the world as phenomenological structure.

His oeuvre constitutes a palimpsest of multi-referential signs that operate in the framework of a weft of hyperbolic syntaxes reverberating on specific themes: the theater, an apartment’s architecture, the plans of cities, maps, which although addressed through traditional representative pictorial forms, are pushed by the artist towards phenomenological territories, in the manner of a noesis or an act of conscious perception and judgment. Kuitca establishes in his work the supremacy of the world as perceived object, as cognitive object.

THE THEATER

The theater as phenomenological subject is the first platform on which Kuitca establishes his “noesis” or conscious perception of the world. In Kuitca ́s paintings, the theater is featured as a vortex of crucial characters and dislocated furniture inscribed within flooded spaces and obssesive monochromatic compositions, which together constitute an underground, an underworld, in an “after- the-disaster” aesthetics where things and beings reflect the traces of a catastrophe.(2) This shadow theater, these tragic scenarios emanate a poetics of the sublime in which the atmospheres are populated by darkness and uncertainty, obliterating the existence of the figures, inspiring a fiction and an imagery of horror. The works of the 1980s, El Mar Dulce (1984 and1986), Siete Últimas Canciones (1986), Si Yo fuera El Invierno Mismo (1986) give shape to an illusionistic space of intrinsic tragedies, with a syntax of figures and objects that follow one another and reverberate back upon themselves. The theatrical space splits into multiple-perspective narrative sub-sets with a visual code that is repeated in all the works: the fragility and dislocation of the figures, the alteration or disappearance of architectonic signs, the blurrings and gouaches in the watery compositions. Here Kuitca designs a tragic Neo-romantic world imbued with strong emotional intensities.

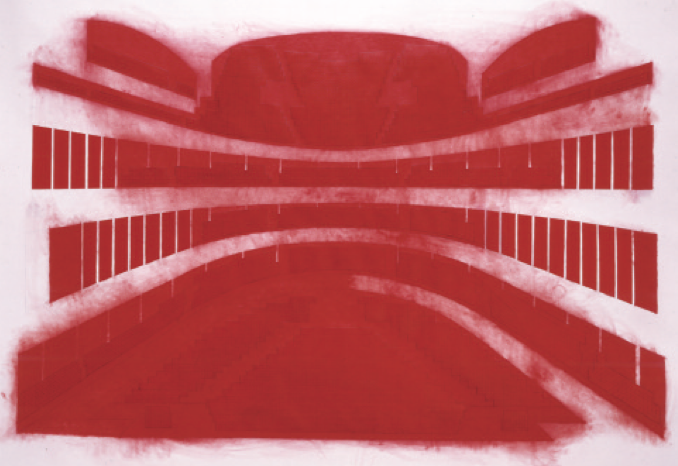

In the 1990s, with the series Puro Teatro, Kuitca resumes the theme of the theater as platform, but inverting the point of view: from the perspective of the stage, he shifted to the perspective of the audience and the seat plan. The appropriated numbered seating plans of different theater charts, downloaded from the Internet and later manipulated with Photoshop, allude not only to social stratification and hierarchy, but also to absence and nostalgia. Mozart-Da Ponte I (1995) is dominated by the theatrical architecture of the seats abstracted into an overwhelming bold red, creating a sanguine space connected with blood and fire. In Teatro Rojo (2004), the artist de-composes the rows of seats into bands of collage, irregularly gluing them onto the black paper in the background, thus creating dislocated stalls, deliriously fractured, like a visual apocalypse of the world.

THE APARTMENT PLAN

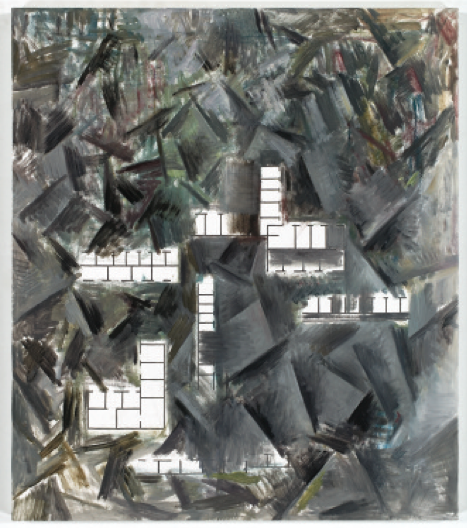

Kuitca shifts towards a more abstract and compact visual structure. The utilization of the apartment plan as a basic architectonic unit dismisses the real to reconstruct it through displacement: the apartment plan shows a basic planimetric sketch that sets forth the intimate and the private (also the existential and the personal), where the protagonists are implicit and are the invisible inhabitants of a socially established space. The apartment plan dictates implicit dichotomies and dualities, and socio-cultural policies, like a “noema” (2) that the spectator reconstructs through conscious and active interpretation of the human life. The apartment plan undergoes mutations with different signic orientations: it is outlined with a crown of thorns, with syringes, or with bones, thus connoting the political content of the work. It is the artist’s oblique way of vindicating his ideological vein. House Plan with Teardrops (1989) shows an apartment plan immersed in white, secreteing drippings redolent of tears, with an enveloping aquatic transparency, in an open allusion to an apartment (as intimate space) that “cries,” in a symbolic way.

THE CITY PLAN

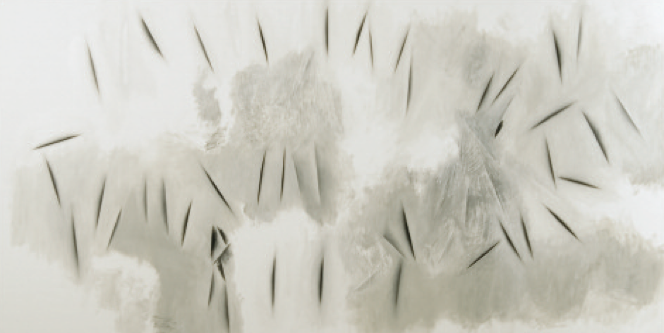

In the 1990s, the city maps made their appearance as metaphors for the large cities, an allusion to the human social space as a contemporary urban territory. In La Tablada Suite, from the 1990s, the artist uses the plans of a prison, a hospital, a cemetery, designed in pencil, as socially charged spaces and as metaphorical references to institutions of power and authority, in an evident political-ideological questioning.

THE MAPS

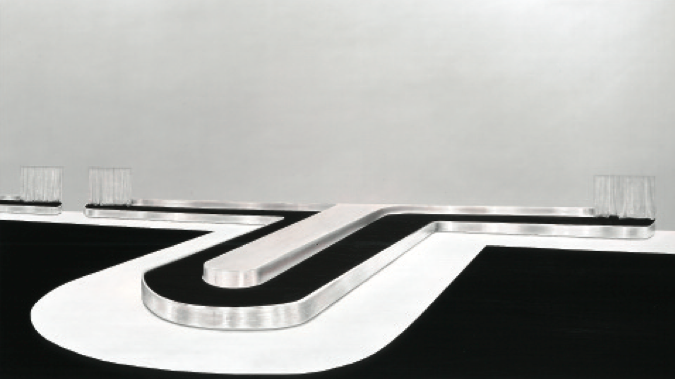

Kuitca’s maps are an allusion to geopolitical territories, to memories of wandering or to cartographies of displacement. Kuitca reinvents the maps, the cities, their names and their interconnections. This use and reinvention of maps already appears as a strategy in the work titled Odessa (1988), in which the artist projects a video still (stored in his memory) of a baby carriage that hurtles down the stairs, from the film The Battleship Potemkin (which he had not seen when he borrowed this image), combined with an imaginary map of the city of Odessa and its surroundings. The work is a mixture of fiction and reality that allowed the artist to recover the memories of his ancestors, who were European immigrants. Particularly noteworthy in the 1990s is Afghanistan (1990), which features a map painted on a mattress, and the cities of Kandahar, Kabul, Herat appear interconnected by main roads; mountains and deserts stand out cartographically through a false hyper realism. Kuitca intentionally resignifies these territories, politically charged for the time. Untitled (1990), features an elaborate map painted on a three-mattress triptych representing part of the US territory. Different cities Fargo, Sioux City, Oklahoma City, Tulsa, Omaha, Grand Forks, St. Paul, Minneapolis appear imaginarily interconnected in a sort of political-ideological inventory. Kuitca’s maps feature itineraires with explosive resonances. Beyond the physical visual quality of the elements, Kuitca’s painting features the purely phenomenological experience, the grandiosity and the internal and existential magnitude of that which is perceived, transcending artistic consciousness: it is his interpretative “noesis“ of the world.