The Velazquez award to Doris Salcedo

recognition of art that opposes oblivion and violence

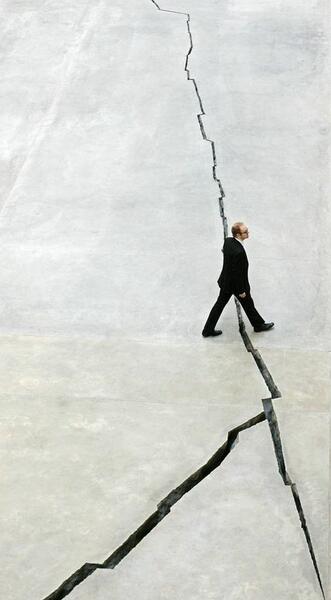

The presentation of the Velazques award to the Colombian Doris Salcedo confirms, once again, how her journey –being silent for a long time, concentrated in the creation, foreign to the social paraphernalia that surrounds the art world- converted her into “one of the most important artists in the contemporary world”, according to the judges’ verdict that Ángeles González-Sinde read at the Spanish ministry of culture. More than that importance associated with her name, which became known worldwide since she opened that unforgettable aperture at the Tate Modern in London, the significance of what the award means to her is associated with an obsession shared with the Spanish master who was recognized for his ability to transmit in painting “the sensation of truth”. Salcedo achieves the same thing with “very humble materials”, as she stated in an interview with Nelson Fredy Padilla in which she reaffirmed de fact that the theme of victims of political violence, “invisible, nameless, missing” are the source of a piece that, more than anything, seeks to “open thinking spaces” and fill with a poetry and an aesthetic that opposes the deeds and days of violence, the places where the barbarie has taken over. “Art- she affirms- counterweights violence and reality.”

Certainly, those installations which take vast empty spaces, with apertures, and piled up objects like sculptures that are metaphors for bodies, formal allegories of the anonymous and massive tragedy of the victims, function as an alternative for the retelling of history. “It means- she emphasized in the aforementioned interview- that we are telling the history of the defeated. History is always told by the winners, and here we have an inverted perspective: we don’t have arcs of triumph, or Nelson’s columns, or obelisks; we have the ruins of war and history. This brings us to work in a piece that articulates the history of the defeated, because we, too, are capable of thinking and narrating our history.”

The aperture in the Tate Modern works, for example, as an open wound in an epicenter of contemporary art: a memory of the space that third world countries occupy in the middle of the hegemonic nations. The fact that their power was established through centuries of looting that financed the extension of modernity is not lost. “The wound has always been there, but I point it out and make it indelible”, Padilla declared in the interview published in El Espectador after the presentation of the Velazquez award. About the permanence of the aperture in the whole of the Tate, metaphor and mirror of “the negative space that we in third world countries occupy”, it would be necessary to add that it also evokes how Latin American that are “educated under the Western canon” continue, according to Salcedo, to be unrecognized as part of the West and are still seen as “the unwanted apprentice”.

Underneath her work she encourages the warnings that Walter Benjamín made about the debacle, the wish to save the salvable that is present in the work of Emmanuel Lévinas, the fervor for poetry of Paul Celan, the view on violence of Goya, but more than anything, the urgency that she has referred to as “being faithful here (In Colombia) to the experiences of the victims. Keeping that sense of social responsibility”. Her way of doing this can be summarized, according to her, in a word that does not exist in Spanish: “Memorials”. Making a memory through the use of sculptures, huge interventions and installations, to evoke, “not heroes or triumphs”, but the contrary. “To remember our dead”. To make “ours” every anonymous corpse hidden by the rivers of oblivion that become wider the older and vaster the violence is.