Artistic Revelations in the Ceramic TileTriennial

Elit/Tile 2010, the Fourth International Ceramic Tile Triennial, held in collaboration with the Igneri Foundation/Art and Archaeology at the Centro León in Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, was one of those exhibitions that exceeds expectations, associated in this particular case to ceramics in the format of floor tiles. It challenged the separation between art and crafts, the boundaries between mediums, and it showed how museography can create a curatorial vision without resorting to a selection of works. The Triennial, which had its inception in Santo Domingo in 1999 thanks to the persevering efforts of artist Thimo Pimentel, president of the Igneri Foundation, exhibited in its fourth edition 357 works from 91 countries, reaffirming the quality and the experimental character of this show that extends the possibilities for signature ceramics.

Although the dimensions were restrained to the standard size of floor tiles (15 x 15 cm), many works that complied with this format and with a medium traditionally associated with utilitarian design were inscribed within contemporary artistic practices. Partly thanks to the influence of the Triennial and to the legacy of figures such as Paul Giudicelli, a movement of young artists exploring new possibilities in the field of ceramics is developing in Santo Domingo. Particularly noteworthy were works by the Dominican artists Pimentel, Carlos E. Despradel, Abelardo Llerandi, Francisco Javier Rosa, Radhamés Carela, and Thelma Leonor, among others. One of the fascinating aspects of the Triennial, dedicated on this occasion to artist Ada Balcácer and ceramist Leo Tavella, was the museographic work directed by Pedro José Vega. This curator and museographer who pays tribute to the Borgean labyrinths and can translate in his spatial conception the balance between minimalist containment and the aspiration to encompass the infinite, structured exhibition halls square-shaped, like the floor tiles which were open and interconnected. Between the black ceiling and the black floor, the viewers moved along this labyrinth of white walls and a tenuous central grey strip where the works were aligned with perfect regularity, with the feeling that they were exploring a universe organized as a whole and capable of offering them, tile by tile, revealing experiences.

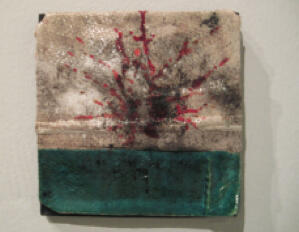

The mounting of the exhibit privileged geographic areas the Insular Caribbean, Central America and Mexico, Eurasia, the Middle East, for instance emphasizing visual correspondences related to the contexts. Cuba featured different explorations of identity. Ismary González presented a cast of her breasts and a label inquiring into the effect of an augmentation. The tile presented out of competiton by Lasseria showed a thumb with its nail painted in white emerging in the center of the red triangle that formed part of an abstraction inspired by the Cuban flag. In the floor tile presented by the artist from Central America, Francisco Munguia Villalta, there were numerous eyes looking southward, where the billboard reading Do not cross the Line was visible. From South America, special mention could be made of the contributions of Chile, Argentina and Brazil, which included works by Patricia del Canto, Claudia Álvarez or Malú Serra, among others. Europe exhibited a nostalgic repetition of folkloric or mythological motifs, in pieces such as the Albanian artist Sedji Bytiqi’s Horse Race, or the German artist Karen Tobías’s re-creation of Leda and the Swan. But there were also works executed with oxides that evoked the bloody conflicts in different countries, such as Bosnia- Herzegovina’s piece by Sonia Rakvick, or the work from the Middle East awarded the Mention by Region, whose author was Faik Alwan. In the US representation, Katharine Perrer’s black crow evoked Poe, and there were philosophical resonances in Jim Bove’s Staifs, or a transfer of minimalist sculpture in Jessica L. Smith’s Articulated Pathways.

At the same time, the labyrinth of tiles revealed constants like the meta-artistic works inspired by the hand that modeled. A beautiful piece of ceramics the winner of the Mention awarded to the African Region was the one presented by Mbanza Diakite. Using metallic oxides and enamel she captured the trace of the fingers immersed in the clay.

Many of the best “tiles” were approximations to abstract and/or geometric forms that may be found in nature. The tile, this small square, suffices to prove that the figurative representation of textures, undulations, spirals, negative spaces of organic bodies, may be at the same time the expression of a poetic dimension. The Igneri Foundation Award to the best tile by a foreign artist, granted to the Canadian artist France Goneau; the Special Award from the Jury awarded to the subtle print of leaves by the Belgian artist Patty Woutters; and the Susana de Moya Foundation Award, the recipient of which was Anika Tender, from Estonia, were proof of this, together with Esteban Quispe’s Oscuro or José Rogelio Vaamondy’s Felicidad. In some cases, as in that of Margieta Jeltena’s Love Letter Landscape (Altos de Chavón Foundation Award to the best concept for a tile), it was possible to enclose the expression of human subjectivity in a single piece which simultaneously re-created an object and evoked natural forms. Buscando Intersticios, by the Argentine artist Martha G. Kearns (ARTes Magazine Award for Sculpture) had the metaphorical quality that its title reflected, as well as an indisputable formal value. There were pieces that permeated the ceramics with the potency of a narrative in progress, or that transferred notions of drawing (from the void to three-dimensional illusion) and of engraving. Such was the case with Inés Tolentino’s hybrid creature, or Leslie Jiménez’s construction, and with Félix Ángel’s work. In sum, the Triennial opened pathways leading to the understanding of the inexhaustible nature of ceramics.