Jorge Méndez Blake

OMR Mexico City

“Ceboruco” tells a story − devised by Méndez Blake himself − that has its origin in the connection between the imaginary space of two volcanoes: the Popocatépetl, which plays a leading role in the plot of Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, and the Ceboruco, the only volcano still active in the northeastern area of the volcanic axis of the Sierra Madre Occidental, in the Mexican state of Nayarit, whose eruptions over the past three thousand years have created an interesting landscape of volcanic rock.

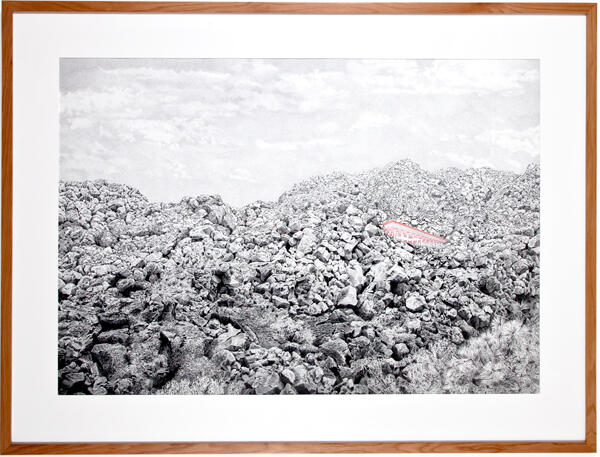

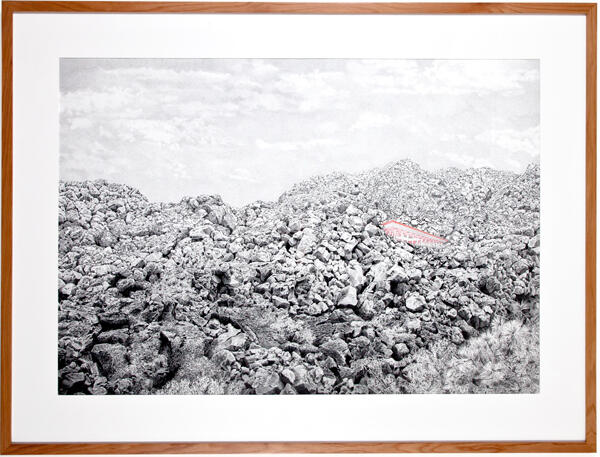

The situations involving the two volcanoes differ − not only because the volcanoes are different, but because one of those situations (the peripheral or implicit one, Lowry’s situation) focuses on the mechanisms of literary fiction, a fiction particularly fraught with symbolism, while the other (the one graphically highlighted by the artist in the work) addresses the attribution by the artist of a kind of archaeological origin to a small and modest building painted in blue and red, and found at the foot of the volcano, or if you will, under the volcano. The same two circumstances converge in the work (painting, drawing and sculpture), in which Méndez Blake suggests that the vestiges of buildings found on the slopes of Ceboruco may be considered indices of a civilization buried beneath the ashes of the volcano.

Nothing − except the artist’s interpretation − indicates that this might actually be true. The “vestige” on which he bases his hypothesis has neither the monumentality of an archaeological site nor the special qualities that would justify its conservation or even its study; however, the artist has decided to revert this situation in order to propose − and almost prove − that history is the result of the purpose that guides the person who records it.

In Ceboruco , a building without an apparent function incorporates the qualities of an archaeological ruin and its history, or at least a documentation of its existence, which it owes to the artist’s will.

In Méndez Blake’s remarkable drawings, some volcanic rocks which are very similar to one another appear suspended in space as a mystery for science or as extraordinary natural phenomena, worthy of the strictest appreciation. In complete isolation, each stone with all its details floats on a black surface − a sheet of paper − recalling a meteorite or a possible talisman, an idol or a volcanic rock. The drawings encourage interpretation. The same happens with the building, Ruina. The representations project it in perspectives that suggest an ambitious and daring architectonic proposal, although this is not actually true, and they highlight its angles and colors, proposing that they possess some relevance. The building’s blue and red colors are used on a huge board on the gallery floor just for the sake of their glorification.

Through attributions conferred to Ceboruco via images borrowed from Lowry and inspired by his own imagination, Méndez Blake articulates a historicist fantasy in which men and ruins are, above all, the interpretation we are all subject to.

-

Ceboruco volcano. View of the pavilion, 2012. Pencil and colored pencil on paper, 57.4 x 77.1 in. Photo: Marco Casado. Courtesy the artist and OMR, Mexico FD. Volcán Ceboruco. Vista del pabellón, 2012.

Ceboruco volcano. View of the pavilion, 2012. Pencil and colored pencil on paper, 57.4 x 77.1 in. Photo: Marco Casado. Courtesy the artist and OMR, Mexico FD. Volcán Ceboruco. Vista del pabellón, 2012.

Lápiz y lápiz de color sobre papel, 146 x 196 cm. Fotografía: Marco Casado. Cortesía del artista y OMR, México DF.