Distant Star

Kurimanzutto, Mexico City

In Los detectives salvajes (The Savage Detectives), Roberto Bolaño described the way in which the real-visceralists, or viscerrealists, walk backward. How backward? Backwards, looking at a point in space but walking away from it, in a straight line towards the unknown. The exhibition Estrella Distante/Distant Star, organized by Kurimanzutto and Regen Projects around Roberto Bolaño’s literary work, corresponds easily with this literary image. It has been curated on the basis of all sorts of connections between the author and the participating artists (or if you will, of intersections, affinities, and fortunate coincidences).

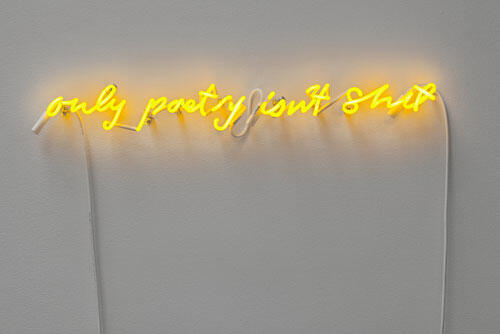

The section that inquires into intersections includes Glenn Ligon’s neon, only poetry isn’t shit, which excerpts this phrase from the impressive novel 2666. This isolated statement functions as the epitome of a new literary canon, which in turn recognizes Bolaño’s inclusion in it.

In Vagabond in France and Belgium, by Carlos Amorales, the artist encodes Bolaño’s story under the same title, using ideograms created on the basis of the superposition of contours of different figures finally to obtain an abstraction of these figures. The piece is the pictogram of the text featured on monumental panels in the manner of a book, and it refers to the central enigma of the story, which revolves around a series of graphic signs or calligraphies which the protagonist cannot read, and which are attributed to one Henri Lefavre, an obscure writer with whom he is obsessed because he is absolutely unknown to him. What is that encoded thing; that which points to the twilight zone in contemporary creation?

In Sorry for the Metaphor, Amalia Pica takes advantage of that same phrase (sorry for the metaphor), also excerpted from 2666, to title a mural work based on Xerox photocopies. In it, a woman holds a poster in front of a lake surrounded by trees in the pursuit of formulating a context with artistic relevance and endowed at the same time with a political voice. The poster seen from the back is a potential slogan, a manifestation of the political spirit that governs a large part of Pica’s work.

Dominique González-Foerster in Untitled 2011, places a copy of Los Detectives Salvajes on a mound of sand. The book is open on page 398, and among the paragraphs included in it, a line attracts attention: “Piero Manzoni! the poor artist who canned his own shit!” This piece, like the canned artist’s shit, is assumed as a search which is ultimately self-referential: Bolaño quotes Manzoni and inquires about his own creation, in a gesture that González-Foerster resumes.

The works of Jonathan Hernández, Vulnerabila (covers), Rikrit Tiravanija, Untitled (los días de esta sociedad son contados), and Thomas Hirschhorn, Concretion Re, express affinities with the work of Bolaño through images associated to some sample of political and/or aesthetic radical stance.

Abraham Cruz Villegas, Carl André, Anri Sala, Daniel Guzmán, Jimmie Durham, Ana Mendieta and Patti Smith, among other important artists, participate in this show featuring works that Bolaño’s readers (myself included) recognize as real visceralist, because they coincide in the anti-resignation, in the poetics of art − even in its crucifixion − echoing a unanimous statement that visceralists make at some point with regard to art: art has always been crazy.

-

Only poetry isn’t shit. Courtesy of the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City. Photograph: Michelle Zabé. Cortesía del artista y Kurimanzutto, Ciudad de México. Fotografía por Michelle Zabé.

Only poetry isn’t shit. Courtesy of the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City. Photograph: Michelle Zabé. Cortesía del artista y Kurimanzutto, Ciudad de México. Fotografía por Michelle Zabé.