Priscilla Monge

“I cannot stop saying things”

Priscilla Monge emerges in the panorama of Costa Rican art, and eventually in the international art scene, in the 1990s. Her artistic initiation coincided with the emergence in Central America of the so-called Post-modernism. This was a simultaneous phenomenon, but she would not be the only artist to coincidentally participate in the new movement, for so did the great majority of Central American artists who currently develop work of merit and interest.

Monge ́s academic training began in the mid-1980s at the University of Costa Rica, an art school characterized by being based on an outdated, practically 19th-century model inherited from Spain and rooted in the more traditional drawing, painting and sculpture. In its corridors one might hardly have heard the words performance, installation or video being mentioned in relation to the practice of art. This somehow explains why Priscilla Monge should initially devote herself to painting, an activity she practically left aside after those first endeavors. However, her early paintings contained the germ of a conceptual proposal in her way of addressing the theme of sexual identity through references related to sports.

The inauguration of Jacob Karpio Gallery in San José undoubtedly had a significant influence. Karpio featured in Costa Rica exhibitions of the works of creators such as Guillermo Kuitca, Fabián Marcaccio, Arturo Duclós and Bill Albertini. The openings of the shows included endless banquets in which we shared with the invited creators extensive and very fruitful dissertations on, for instance, the meaning of being a Latin American visual artist, or thoroughly analyzed the works of other creators who aroused our interest, as for example the Brazilian Hélio Oiticica or the Chilean Eugenio Dittborn. Through these conversations, Monge discovered Luis Camnitzer ́s conceptual oeuvre, which had a strong and lasting impact on her work. After her fleeting passage through painting, Monge continued to use a two-dimensional format, but for the first time, she began to include texts in her creations. She expressed her concern with gender issues by introducing in the formal solution of her works a series of allusions to crafts and modes of expression (embroidery, for instance) which we all identify with the “feminine”. In one of her early series, Las sentencias (The Sentences), she makes reference to the penalties that were applied, in colonial and post- colonial times, to women who disobeyed certain behavioral precepts. The Sentences clearly marked the end of a first stage of more traditional expressions, and insinuated a path more in keeping with conceptual art linked to words and texts.

In 1994, Priscilla Monge settled in Belgium, where she made the acquaintance of artist Wim Delvoye. This would turn out to be an essential influence for the development of her work, since Delvoye based his work on re-interpretation, humor – and quite often –, on the utilization of the written word in his work. Fundamentally, Delvoye would have an incidence on her way of developing her work, from its planning and execution to the daily discipline of writing down ideas and keeping artists ́ notebooks containing notes and sketches for future works. Many of the ideas which the artist developed in the course of the following decade had their source in the four years she spent in Belgium.

At that time, Priscilla was interested in exploring the third dimension through a series of objects which she re-signified. To this end, she allowed the surfacing of a subject that she found particularly disturbing: violence, whether veiled or open, structural or gender-based. From this period dates Cállese y cante (Shut up and sing), which she presented in 1997 at the 6th Havana Biennial. Using such disparate elements as music boxes and boxing helmets, Monge manages to tune up her discourse until attaining a synthesis in which fragility and brutality appear terrifically and fatally amalgamated, as if one could not exist without the other. It is in this work that we can first recognize one of the most characteristic stylistic axes in the work of this artist: that of duality. A duality linked to the paradox of contradiction, and one which the artist would later explore in many different ways.

On some occasions, Monge ́s work has been interpreted as ambiguous. I think hers is, rather, an oeuvre in which amphibology expresses more clearly her true intentions: amphibology always suggests two or more interpretations and it is always ambiguous. Ambiguity, on the other hand, cannot be amphibological, for it makes reference to equivocation and uncertainty rather than to a twofold sense.

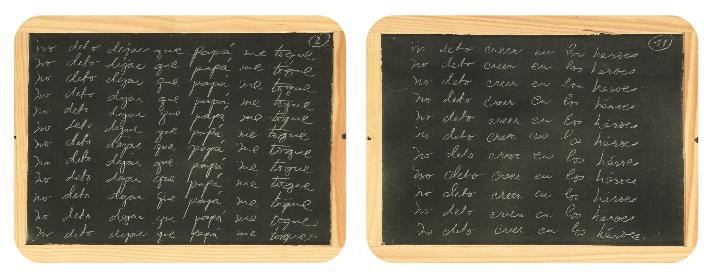

Pensum is the title of a work the artist executed in 1998 and presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design in San José. It was an emblematic work in which, resorting to several dramatically illuminated blackboards, she reproduced the well-known disciplinary punishment of writing down ad nauseam an admonitory phrase, as for example, “I must not sleep with curators”. The blackboards also showed blots and crossing-outs, unequivocal signs of rebelliousness and irritation.

With a series of micro-stories and the help of Karla Ramírez, who urged her to transform them into videos, Priscilla made her debut in the field of video art. Outstanding in this production is her short film entitled Lecciones de maquillaje (Make-up Lessons): a professional make-up artist calmly explains the steps to be followed to do a woman’s make-up. The model, passively seated, allows him to do his work, and when the camera finally focuses on her face, we notice with surprise and horror that it appears to be full of bruises and blows, as if she had received a tremendous beating.

Towards the year 2000, after exploring the field of video art and, in a certain way, as a logical extension of her interest in it, the artist’s attention was drawn to photography. Her initiation in this discipline is marked by large-format photographs in which the texts, featured as letter soups or graffiti on coffee cups, introduce ironic references to the theme of art: “art is a matter of life and death”.

Since then, photography has been her means of expression. Her most recent creations include female display models to which the artist has clumsily applied make-up, and in which the blusher and eyelash mascara have run to the point of transforming these figures into caricatures. Monge ́s works are currently on display alongside those of artists of such stature as Andy Warhol, Joseph Beuys, Sigmar Polke, Hélio Oiticica, Luis Camnitzer, and Victor Grippo, among other great artists, in the exhibition “Face to Face”, which for the first time gathers together the two Daros Collections in a single show. Priscilla Monge has become an indisputable referent for the new generations of artists from Central America and the rest of the American Continent. An artist whose personal “slate” appears to say: “I cannot stop saying things”.