Pablo Vargas Lugo

TIME BELLY

I first came across the work of Pablo Vargas Lugo (Mexico City, 1968) in the late 1990’s around the time that his seminal pieces Finale (Japón) (1995), Naked Boeing Mandala (1998), and Visión Antiderrapante (2002) began to exhibit internationally, thus becoming referential outside of Mexican contemporary art circles. At last, widespread overarching media debates were finally dying out in Latin American cities and instead, artists affiliated with groups like Temístocles 44 and La Panadería (in Mexico) emerged in light of their socially and politically infused works and the irrefutable conceptual rigor they attached to them. While Vargas Lugo was connected to these groups, his work isn’t exactly representative of the movement, but lingers amongst other in-betweens.

I’d argue that what makes Vargas Lugo’s work singular is its relationship to formalism. More precisely, it asserts that through form, language can be neutralized and circumvented. While it is conceptually triggered, it isn’t ephemeral or performance based; in fact it embraces a varied amount of media such as painting, collage, sculpture, installation and video. Also, while the work is dialectical, alluding to communities, structures, and action, it isn’t politically derived or driven. Rather, it pinpoints one’s sense of place and position in the stream of life, or oppositely, how it can become dislocated by its own conditions of measure. Through sources and forms as divergent as flags, weather diagrams, astronomical charts, maps, newspapers, charts, coins and carpets, it questions the conventionality of signs and the cues surrounding them, often in a format that one could describe as an ensemble. Furthermore, it is characterized by an apparent simplicity that emphasizes the ways in which representation can be underlined by hope, belief, exchange, recognition, and philosophical transformation inside the belly of time.

Around the years of multiple shows at institutions like the Jumex Collection as well as his participation at the 26th Sao Paulo Biennale, which earned him solid recognition, Vargas Lugo was commissioned to make a large-scale installation at the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros (SAPS) called Vague Statistique (2003). Since I just had taken a post as curator there, the show impacted me rather directly. I recall it as a sort of time vessel: it included a tower of three television monitors called Relojes I, II, III (2003) displaying animated sequences of clocks running at different rates so as to divide time into prime numbers, all lasting 24 hours. The clocks would only coincide at midnight, and from 00:00:00 they would start drifting from each other. In the same room, a large truncated pyramid sculpture titled Gondwanaland (2003) rested in the middle. Crafted out of concrete (what we could image as sediment) it featured a blue wave (what we could imagine as water) inlaid into the sculpture. Both pieces cross-referenced a graph projected in the corner whose rapidly ascending and descending data could only be speculated. Mulling over the installation’s uncanny correlation to market speculations or how technology influences our undying need to reveal the bones of yesterday, not to mention the future, I recently pulled out a text that Vargas Lugo wrote for Vague Statistique – now eight years later.

In the essay Vargas Lugo writes about a man and a machine he meets when visiting a currency exchange center in India. Vividly he describes a place that is dust plagued, though certainly visible for one odd detail. While it was the year 2003, a huge and clearly operative graphic display ticked away in the room, illustrating data, not from 2003, but from the first trimester of 1999, and in London. Across the desk sat a cashier peering into a screen tallying up a pool of numbers and registers based on the current rates of the stock market. The artist couldn’t wrap his head around the paradox and to further the quandary, as he describes, a messenger had scurried off just seconds before to return 10 minutes later, handing over a bag of money from the bank around the corner that he didn’t opt for earlier that morning because it advertised a lower rate. Vargas Lugo’s story seems to offer a speculation. What could have happened if the messenger who rushed off to get a better conversion percentage for his office, had ran not only a few blocks away, but backwards by three weeks? Would the world be the same place or significantly different? Could it have been the year 2010 while I calmly read his exhibition notes? Or does my inquiry simply lie in a vague statistic?

Speculation, fractures, encodings, and the art of prediction (and the contradictions these travesties propose) more than often surface in the artist’s work, as illustrated in the pieces Estrella Rota (2008), Hamadryas Guatemalena marmarica Mandala (2007), Fortuna (Timex-Rolex) (2008). However, I’d like to point to two bodies of work since the artist’s move to Peru in 2008 that properly synthesize his recent work. One is a public sculpture, performance, and exhibition titled Eclipses for Austin (2009) and the second, Historis Odius (2010), is a set of pieces emphasized by birth, metamorphosis, and archetypal depositaries for idealizations and aspirations.

The Eclipses for Austin project came into being in light of research around community action and the politics of usage and deployment. It references mass entertainment techniques and how commemoration influences the creation of political terrains via propaganda. And while the videos point to the sportive practices of certain radicalized militant groups, like the Shining Path, or the propaganda driven Arirang Mass games held in North Korea, Vargas Lugo’s motive is less political and more geared at ritual. The piece, commissioned for his solo show at the Blanton Museum of Art, follows two hundred volunteers gathered at the Darrell K. Royal Texas Memorial Stadium at The University of Texas at Austin, in an effort to artificially stage four solar eclipses portrayed as they will be seen from that exact geographical positions in the years 2024, 2200, 2205, and 2343. The resulting video document the respective trajectories of sun and moon, whilst the groups sat in a circular arrangement, flipping two-sided cards in a choreographed performance each generating the feeling of real time animation in motion. Conceived as a ceremony for future events and how eclipses and sporting relate in terms of observation and ritual, the videos were later exhibited at the Blanton galleries alongside a newspaper piece and an accompanying soundtrack.

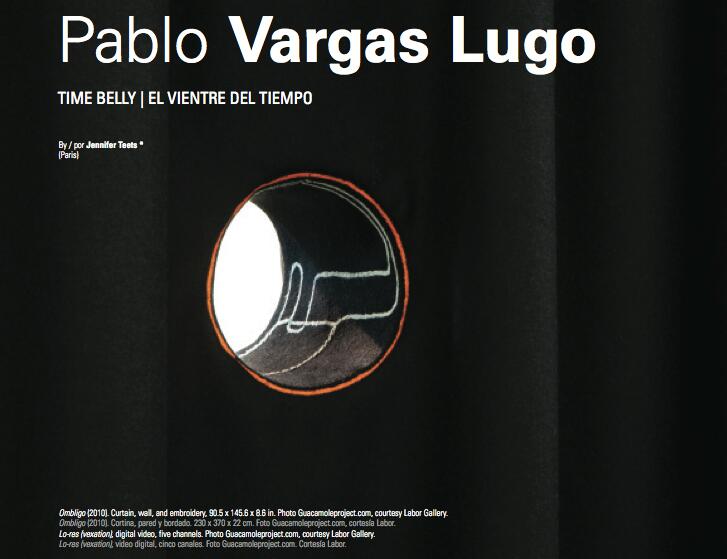

The Historis Odius bodies of works, as displayed at his recent solo show at LABOR in Mexico City, are more notable for their explicit self-referencing and historical musings. Specifically, the piece Ombligo (2010) illustrates a form of blindness to historical context. It bases itself on an ancient Mayan vase depicting a maze of elevated states of birth and existence, with characters strung together by an umbilical cord. Vargas Lugo, inspired by the vase, reinterprets the piece by crafting a veil or more properly, a curtain with an incision that one could associate with a voyeuristic glory hole or happy hole. In this case, the diameter and length of the hole measure the same as the actual Mayan vase. Here though, Vargas Lugo erases the characters, and what remains of the drawings is rendered as if seen from the inside. What is obscured by the curtain is, metaphorically speaking, the historical context of the vase, the world that developed around its use. We are left with the hole, suggesting both the physical memory of an intimate connection, or a voyeuristic device that enables all forms of speculation to flow around it.

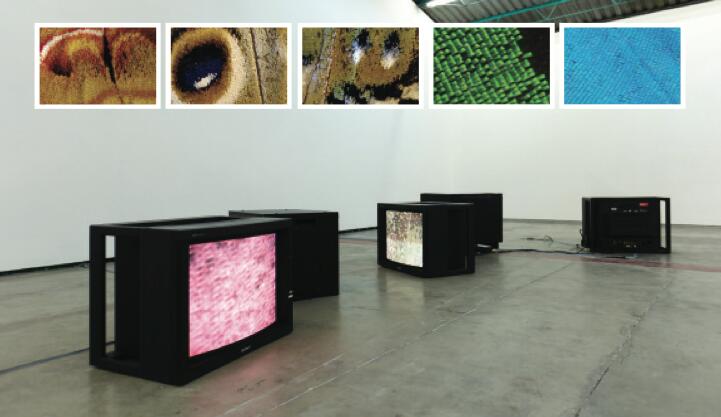

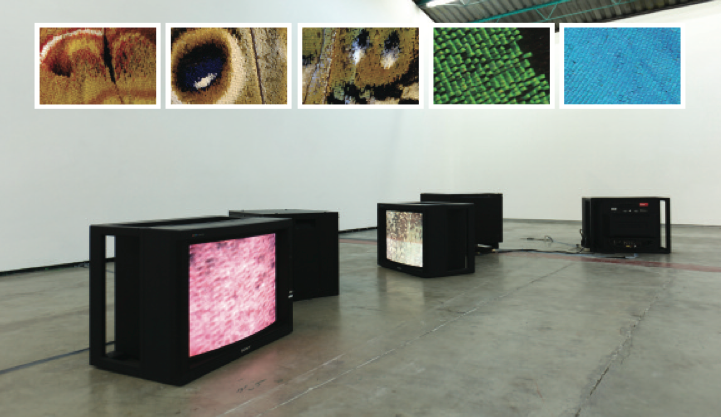

Too, flags and varying textiles forms are replicated in the show, as if to suggest the notion of birth, flight and emergence. Carrying the title, Historis Odius (2010) like that of the exhibition, a central flag sculpture crystallizes around another form of blindness to context, in this case related to nature. That is, how a butterfly evolves a pattern that camouflages itself, startles a predator, or mimics other butterflies with great exactitude by being gazed at by other species and individuals, not by any kind of self consciousness. Flexibility and binary interpretations are attached to the each of the works, and new calligraphic forms are explored in a wall piece, which references both graffiti and Mayan scripts based on layered writing. All in all, the ensemble gives the feeling of a subdued and incredibly codified theme park, in which reading and seeing are the central tasks at hand.

* Jennifer Teets is an independent curator and writer currently residing in Paris. She was the 2009 Curator in Residence at the Kadist Art Foundation in Paris, and from 2003-2007 spearheaded the contemporary art program at the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros (SAPS) in Mexico City.

Profile:

Pablo Vargas Lugo (Mexico City, 1968) studied Fine Arts at the National School of Visual Arts, UNAM. His most important solo shows include Eclipses for Austin, at The Blanton Museum of Art, Austin (2009), Contemporary Projects, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2005) and Congo Bravo at the Carrillo Gil Museum, Mexico City (1998), among many others. His work has been shown at the 26th Sao Paulo Biennial and the 5th Mercosur Biennial, and at institutions such as the Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, PS1 in Nueva York, UCLA Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, OPA in Guadalajara and the University Museum of Contemporary Art in Mexico City, having presented over a hundred solo and group shows. He currently divides his time between Lima, Peru, and Mexico City, Mexico.

Vargas Lugo’s work is represented in numerous public collections, most noteworthy among them the Carrillo Gil Museum, Mexico F.D.; the University Museum of Contemporary Art, Mexico F.D., Los Angeles County Museum of Art ; The Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; ARCO Collection, Madrid; the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art; the Banco de España; Jumex, Collection, Ecatepec, Mexico; UCLA-Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; the Galician Center of Contemporary Art, Santiago de Compostela, Spain; and Artium, Vitoria, Spain.