Juan Manuel Echavarría

Countering Silence

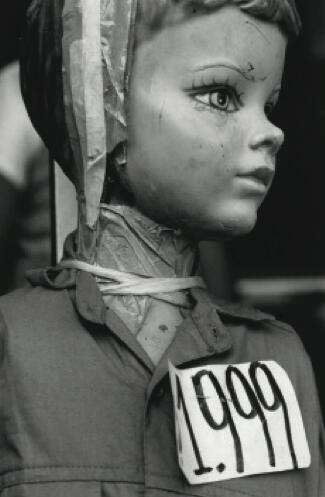

Juan Manuel Echavarría was a professional writer for many years when he set aside his literary endeavors and, in measured steps, turned his creative and intellectual attention to art. The turning point occurred—incredible as it may seem—when Echavarría came across some damaged mannequins on the sidewalk in front of clothing stores in a poor neighborhood in Bogotá.

No one seemed upset by their battered appearance as they occupied a central place in the midst of everyday commercial life. In plain sight, a female mannequin had her neck taped to keep her head and body attached to each other. [ILLUSTRATION 1] Another mannequin had large cracks in her head with scarlike lines running across the forehead and along her nose and cheek. A male’s head had a large hole in it, and his face was further marred by significant areas of peeling paint. Another’s skull, held together with tape, obstructed the beauty of her delicate, pretty face. Their beat-up condition greatly affected Echavarría who, unable to forget their unsightly appearance, associated their mutilated bodies with victims in the ongoing civil war waged by narco-trafficers, right-wing paramilitaries, and left- wing guerrillas. The serendipitous encounter awakened the artist’s social consciousness, resulting in his first series of photographs titled Portraits (1996).1 That series changed the orientation of his practice and got him out of the studio onto the streets and into rural areas where the war was being waged.

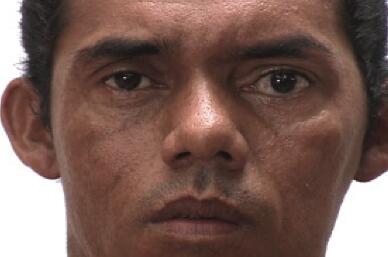

In exchanging pen for camera, Echavarría relied on metaphor and metonyms to communicate pain and sorrow as well as the faith expressed by Colombians in the face of systematic devastation and brutality. The video Mouths of Ash, of 2003-2004, features seven people singing a cappella of their personal ordeals. One of the singers, Dorismel Hernández, met Echavarría who was with a group of friends in a restaurant in the town of Baru, the name of one of Colombia’s islands. [ILLUSTRATION 2] Dorismel approached the group and asked if he could sing for them.2 The following verses illuminate the singer’s sentiments: “When I was handcuffed, was tied up / I prayed to you for my brother and me/ And at that moment you were listening to me / And that is what makes me so happy / Oh, when they were massacring, when they were killing / I felt, I felt like crying / I only prayed to you, my God up in heaven / That you would save us, and nothing would happen to us.”

3Echavarría was so moved that he asked Dorismel for permission to record him. Anticipating that many others might have turned their travails into music, the artist began a journey that had significant personal as well as aesthetic impact. He attended Afro- Colombian symposiums and festivals in the region of Choco, where he met many singers who had composed songs about their personal histories.4 Mouths of Ash was shown at the University of Los Andes in Bogotá, which most of the seven singers attended. The video camera framed the face of each singer, recording their expressions at close range, providing a sense of intimacy as they communicated their deeply felt emotions. The audience was moved by the dramatic narratives.

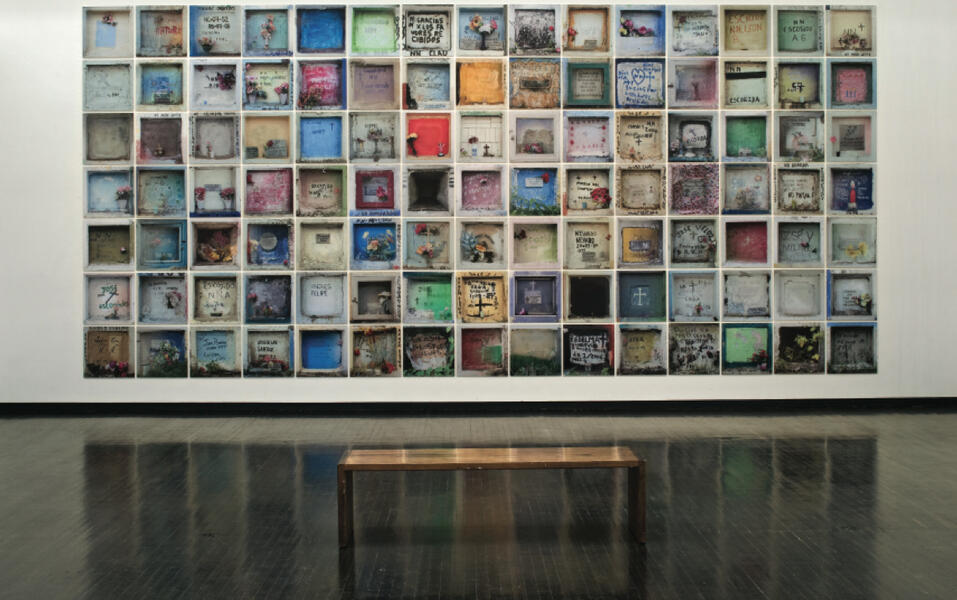

5 An extraordinary act of faith and solidarity took place in Puerto Berrío, small town north of Medellin on the banks of the Magdalena River. In the cemetery of that war-torn town, hundreds of tombs with the remains of unidentified persons have been placed in mausoleums. [ILLUSTRATION 3] Echavarría first visited that cemetery in November of 2006 during the Month of the Souls when at midnight the townspeople entered the cemetery to pray for the dead. There Echavarría had a unique experience—people were praying at individual tombs marked with the initials NN, standing for no name. In a great “gesture of humanity,” local residents had adopted tombs of unknown people whose bodies had been rescued from the river.6 In adopting the tomb of an NN, the people, who assume the task of caring for it, also feel the right to petition the soul for a favor. Many tombs have messages thanking the soul for favor(s) rendered; others are decorated with flowers or have the date of adoption; some have given their family’s name to the NN.7 The photographic series Requiem NN continues, as does the humanitarian gestures of the residents of Puerto Berrío, who by adopting the final resting place of former countrymen refute erasure in the face of unspeakable violence and death.

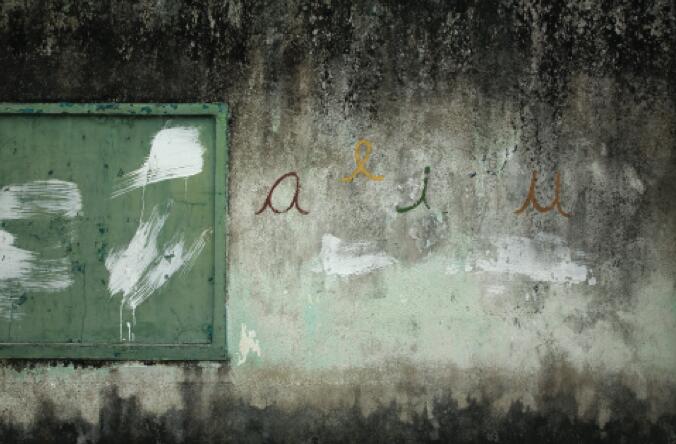

8 The artist began a new journey on March 11, 2010 when he went to the town of Mampujan for the commemoration of the tenth anniversary of the day the villagers had been forced to leave their homes and land. (The town, in the mountainous region of Montes de María, has never been reoccupied.) During the course of that day, Echavarría found a deteriorated school with a blackboard on which the vowels a, e, i, and, u were still legible. Time had worn away the o, the very letter that became the title of the exhibition, La “0.”9 [ILLUSTRATION 4]

He also photographed objects people had placed in the interiors of the abandoned houses (Desenterrar y Hablar I and II). A tapestry hung in a ruined home; in another, a vase of flowers was on a table with a tablecloth. The photographs of these objects speak to memory and a brief reclamation of place. [ILLUSTRATION 5] Composed as a diptych in dialogue with each other, they become neighbors. Images of the same ruined interiors also capture two truncated tree trunks with roots growing above the ground: symbols of mutilation, metaphors for forced displacement and uprooting. Another astonishing discovery was a blackboard with the sentence Lo Bonito es Estar Vivo (To be alive is beautiful). The words, just legible enough to decipher, convey the essence of what had become life’s imperative—to stay alive. Although we do not know when the message was written, clearly the unidentified person wanted to express his or her resistance to what had become the objectification of death.

Echavarría went to the nearby hamlet of Limón, which consisted of a group of scattered houses known in Colombia as veredas. [ILLUSTRATION 6] There he photographed The Witness, featuring a young calf in front of a blackboard. Vowels had been written above the board and numbers on the wall beside it. The calf functions as the chronicler of the hamlet’s history, reminding us by its presence that learning was abandoned and the schoolyard is now a grazing field. The artist continued on to Bellavista in Bojayá in Choco to photograph blackboards where the writing had disappeared. (In 2000 the church in the village was the site of a massacre.) Several photographs are titled Silence—a noun meaning absence of sound, or oblivion, obscurity, existential conditions endured by thousands of Colombians who fled or escaped kidnapping or remained hidden. [ILLUSTRATION 7] Silence, ironically, is precisely the word that speaks to us in these photographs through the mutilated mannequins, the songs of survivors, the writings on tombs and the blackboards, even those with no messages—a formidable photographic reckoning.

1 The entire series, together with the artist’s comment, is reproduced in Laura Reuter, ed., Juan Manuel Echavarría: Mouths of Ash (Milan: Edizioni Charta and Grand Forks, N.D.: North Dakota Museum of Art, 2005), pp. 36-41.

2 The artist communicated the backstory to the author by email, 8-01-2007.

3 The entire song is reproduced in Reuter, p. 142. In 2007 I showed a segment of Mouths of Ash of Dorismel and his brother Nacer Hernández (Two Brothers) to graduate students at Catholic University in Santiago in the topic: War and Violence.

4 Echavarría selected and recorded some fifteen singers; in the editing process he selected seven.

5 I first saw the video at the Americas Society in New York in 2006 in a program titled Colombia: Voicing the Conflict. This audience too was deeply moved.

6 It has become customary for local fishermen to rescue decayed bodies or body parts that float down the river as if it were a common grave. The remains get turned over to civil and religious authorities, which provide burial places and rites.

7 The artist visits the cemetery in Puerto Berrío about three to four times a year and continues to document the changing tombs.

8 Requiem NN, 2006- was exhibited in Ciudadela Educativa y Cultural América, Puerto Berrío, Antioquia, Colombia (2010); Galería Sextante, Bogotá, Colombia; and Josée Bienvenu Gallery (2009); Museo de Antioquia, Medellín and North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks (2008).

9 The exhibition opened in February 2011 at the Joseé Benvenue Gallery in NewYork.

Profile:

Juan Manuel Echavarría, born in Medellín, Colombia in 1947, lives and works in Bogotá, Colombia. He is presently represented by Josée Bienvenu Gallery, New York and Galería Sextante, Bogotá. His first solo exhibition was at B & B International Gallery, New York (1998). His solo museum exhibitions in the US include: Emison Art Center and Gallery, DePauw University, Greencastle, IN (1999); North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks, ND (2005); Weatherspoon Museum of Art, Greensboro, NC (2006); Santa Fe Art Institute (2007). In Europe solo exhibitions include: Erich Maria Remarque Peace Center, Osnabrück, Germany, (2003); Malmö Konsthall, Sweden (2007). In Latin America solo exhibitions include: Museo de Arte Moderno, Buenos Aires (2000); Museo de Arte Moderno La Tertulia, Cali (2003). Group exhibitions include: Korean Kwangju Biennial (2000); Daros Latin America, Zurich (2004); Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki (2006); Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (2005); El Museo del Barrio, New York (2007); Valencia Bienal, Spain (2007); Kunsthalle, Vienna (2007). His videos have been shown at many festivals and exhibitions throughout the United States, Canada, Europe, and South America. Before becoming an artist, he published two novels, Moros en la costa (1991) and La gran catarata (1981). He is the founder and president of Fundación Puntos de Encuentro.