Eduardo Costa

Art Permeated by Language

John Perreault: “At the end of the 1960s, when we were part of a group which included Scott Burton and Vito Acconci, among others, it seemed that your forte was to invent a basic innovation and, based on it and on the “ism” it generated, begin to construct your work. ¿Do you still believe that is what must be done?”

Eduardo Costa: “Yes”(1)

Indeed, since the mid-1960s, when he began his artistic activity, Eduardo Costa has worked at the limits of genres and institutionalized disciplines. “Media Art”, a genre he created jointly with Raúl Escari and Roberto Jacoby in 1966, left the existence of the artwork in the hands of mass-media operations. That same year, while still living in Buenos Aires, together with Jacoby he created another genre, “Oral Literature”, which resorted to the tape recorder as technological tool to capture, through the voice, that of which writing could only give partial evidence.

With the idea of reproducing as images and text the style and metaphors applied to the description of clothes in fashion magazines, Costa created imitation jewelry, ears of gold, golden hairs to intertwine with the models ́ hair. This was the origin, in Buenos Aires first and later on in New York, of the “Fashion Fictions” series (1966- 84), works that challenged fashion as an institution and fashion ́s dissemination channels by gatecrashing into them and forcing them to reflect on their norms and possibilities.

“Names of Friends: Poem for the Deaf-Mute” (“Nombres de amigos. Poema para sordomudos”) (1969), once again placed the emphasis on language. If Costa had previously sought oral equivalences for the visual, in this silent film in which he mentions 53 friends, he inverts the search and speculates on identifying the labial mimicry which corresponds to the sounds of the names, to the oral element. In sum, since then Costa has produced an intercrossing of genres and languages, an information exchange and translation which clearly situate his work in the field of conceptual art.

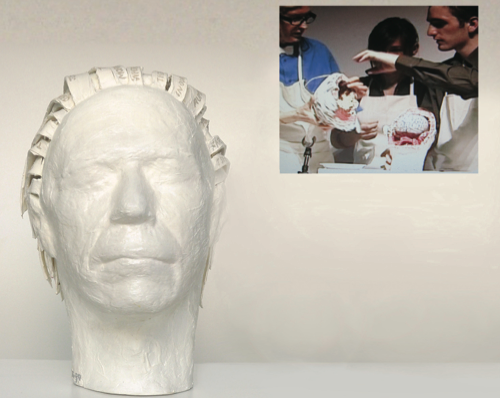

The 1960’s and 1970’s were years of reflection on art as a means of communication and on its aesthetic and political scope, years of dematerialization, as Lucy Lippard – and before her, Oscar Masotta – defined them. On the other hand, Eduardo Costa ́s current work, a series whose origin dates back to 1994, explores the materiality of a traditional practice – painting– with the aim of forcing it to experience a crisis from within, in terms of what is specific to it. Due to certain random circumstances associated to his technique, a bottle of acrylic paint that was left open in the studio dried up and became a thick paint cylinder. Voilá...! A plastic utopia come true: paint could have volume, it was not necessary to represent the three-dimensional on the plane! Thus, layer upon layer of acrylic paint gave rise to the lemons consisting entirely of paint; to the fish, the eggs (with their yoke inside) and so many other paintings by means of which Costa proposes to the viewer a conceptual operation: to get rid of the notion that three-dimensionality is the exclusive patrimony of sculpture and assume that it may also characterize painting, provided that the internal space is worked upon. Thus, these works are paintings because they are made of paint and bacause they achieve something that sculpture cannot: while a sculpture is homogeneously made of stone or wood, Costa ́s paintings represent in their inside the organs of the head in the case of a portrait, the pulp of the fruit, the flesh of a fish, the glass of a bottle. In the words of Luis Pérez Oramas, “A powerful sincerity underlies these works: they are ‘materialistic tautologies’ in which ‘paint is paint’”(2). But it is undoubtedly the enunciation that provides the condition of existence to this new type of object, the volumetric paintings. In this case, as in many others within the framework of historical conceptualism, it is the shift in the interpretation of an object, the change of context that renders the existence of the new practice possible.

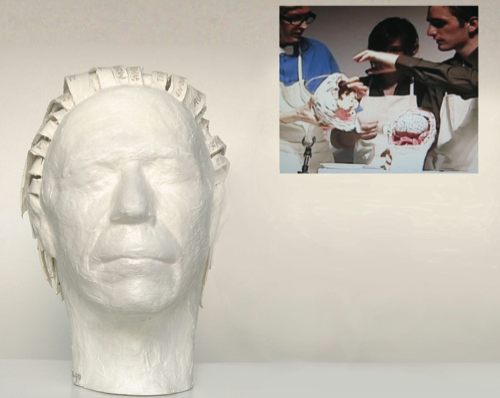

In 2004, Costa staged with his works a “didactic performance”, at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires. In The Anatomy Lesson (Homage to Rembrandt), he generously illustrated the change in perception that his paintings imply. He opened up fruits to show their fleshy interiors; he dissected the skull of his friend, the poet Carter Ratcliff, in order to show the brain. Finally, he broke eggs to show us their yellow interior. Those of us who participated in that magical session collectively partook of the fiction that actual fruits were being opened: the illusion of painting materialized once again. The performance gave evidence of the tacit agreement on which painting is based: that of being a mode of representation.

Along the same path that painting followed in the context of Art History, Costa later oriented his naturalistic volumetric paintings in the direction of geometry (spheres, cylinders, prisms, parallelepipeds) and immediately after that towards abstraction, represented by his current expanded monochromes and bichromes, and soft paintings. Indeed, Costa ́s oeuvre is assembled in such a way as to continue, and occasionally break with, different local and international pictorial traditions. If it is true that the geometric monochromes were formally attuned with the frequency of concrete art, and at a later stage, of minimalism due to their expressive and significant reductionism, it is equally true that they are also the forms freed from their frame that the Argentine master of Perceptism, Raúl Lozza, advocated for. The Rioplatense concrete artists utilized, in the context of a very combative program, the irregular and trimmed frame, the shaped canvas, which would later be developed by minimalism in the United States. In this way, they proposed a painting in which the forms on the plane would be determined by the contour of the frame – just another way of becoming more removed from representation by abolishing the window-format to which the frame is historically associated. Going one step further, Lozza extracted the shapes from the plane of representation and placed them directly on the wall: concrete shapes that represent only themselves on concrete surfaces, the space, the environment.

Costa ́s expanded monochromes share with Perceptism the idea of exceeding the frame, of going beyond it, one might say that with a certain irony of tone that seems to quote expressionism and its mythical excesses; the viscerality in the application of paint. Brutalist works, they overflow because the load of acrylic they bear is such that it flows towards the perimeters.

In the process of analysing painting, Art History and Costa with it had eventually deprived this discipline of everything that apparently belonged to it: narrativity, the reflection of reality, the need of a support and a frame, planimetry, representation. The only thing painting had left was its materiality. Some of Costa’s latest works are mounted on the wall, with the aid of small shelves, and they arch fluently. Canvas is either not used as their support, or it is included within them, swallowed up by the acrylic paint. In the same way as in the Fashion Fictions the artist appropriated the literature characteristic of fashion, in Pedazo de mar/Piece of Sea, he appropiates the literature of technical description, and redefines in a canonical tone this other new object as “acrylic on and beyond the stretcher”. Once again, language permeates the meaning of the work.

Aligned with the innovative tradition of the avant-garde, Costa invented several genres: Media Art, Oral Literature, Fashion Fictions, Talking Paintings (paintings that talk about themselves via a tape recorder), Volumetric Paintings, Soft Paintings, and the Expanded Monochromes and Bichromes... With an imagination enriched both by Marcel Duchamp and by one of his teachers, Jorge Luis Borges – the two of them incorrigible creators of fictions – Costa ́s paintings are, in the words of Alexander Alberro, “”the result of a wide range of concepts and legacies whose complex synthesis provides a glimpse of how modernist painting can be productively reformulated in the twenty-first century”(3).

(1) John Perreault, Entrevista a Eduardo Costa, en Eduardo Costa: Volumetric Paintings, Cecilia de Torres Ltd, New York, 2001 (2) Luis Pérez Oramas, Antiquity and Modernity of the Portrait, in Retratos: 2000 Years of Latin American Portraits, San Antonio Museum of Art, Smithsonian Institution, El Museo del Barrio, 2004 (3) Alexander Alberro, Reformulating Modernist Painting: Eduardo Costa’s Geometric Abstractions, in Eduardo Costa: Volumetric Paintings, Cecilia de Torres Ltd, New York, 2001

Profile:

Eduardo Costa is an Argentine artist who lived twenty- five years in the US and four in Brazil. He started his career in Buenos Aires as part of the Di Tella generation and continued to work in NYC, where he made a strong contribution to the local avant-garde. He collaborated with American artists Vito Acconci, Scott Burton, John Perreault and Hannah Weiner, among others. In Brazil, he participated in projects organized by Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Pape, Antonio Manuel, Lygia Clark, and others from the school of Rio. His work has been discussed in Art in America, Art Forum, and in the main books on conceptual art: A. Alberro, MIT, 1999; P. Osborne, Phaedon, 2002; Mari Carmen Ramírez and Héctor Olea, Yale/Houston Museum of Art, 2004; Inés. Katzenstein, MoMA, New York, 2004, Luis Pérez- Oramas and others, San Antonio Museum of Art, 2004; Luis Camnitzer, University of Texas, 2007, among others. Eduardo Costa ́s work has been exhibited at the New Museum, New York; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid; Queens Museum of Art, Queens, New York; List Art Center, Boston; Miami Art Museum, Walker Art Center, Minnesota, MOMA, Buenos Aires; Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, among others. A current project is to manufacture 30 Duchamp/Costa bicycles inspired by a 1980 model, for an exhibition on Duchamp-based work curated by Jessica Morgan (Tate Modern) for the Jumex Foundation in Mexico City.