Antonia Eiriz

MDC Museum of Art +Design (MOAD), Miami

There are artists who have had such a colossal impact at a given stage in the history of their countries’ art and such a marked influence on the successive generations that no tributes will ever suffice.

Such is the case of Antonia Eiriz, an exceptionally influential Cuban painter who resisted sharing the pro-government rhetoric which, at the time of her artistic blossoming, restricted the sacred act of creation. The exhibition Antonia Eiriz: A Painter and Her Audience, curated by Michelle Weinberg, proposes a recapitulation of the crucial transit of this controversial artist across the contemporary panorama of the visual arts through a rigorous selection of more than forty works that reflect her ferocious expressive intensity, which remained in constant antinomic tension with circumstantial manipulations of power, as well as with frivolous sensory satisfaction or concessions to the market.

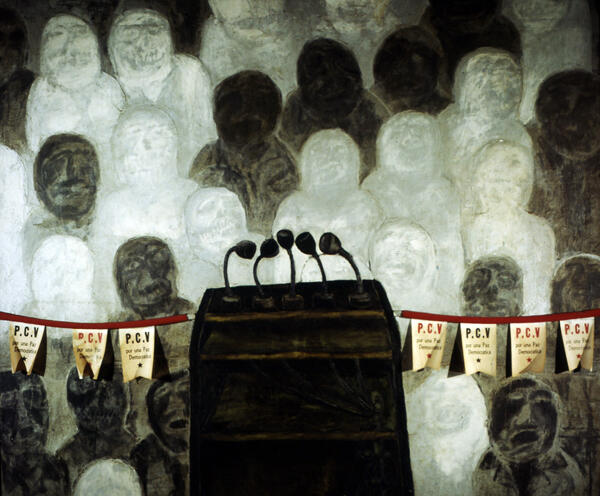

The curator resorts to four exhibition blocks to guide an exploration that begins with the reproduction of the memorable canvas Una tribuna para la paz democrática (A podium for democratic peace), 1968 – the original work is included in the collection of the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana – and culminates with a 1995 project which was left unfinished before her death that same year. The selection takes visitors on a tour of the inclement poetics of a temperament that relied on a sharp intuition to tune to the dystopian zones of the social environment, and reveals affinities with the work of masters such as Goya, Munch, or Bacon, perhaps as a result of the shared obsession of plunging into the darkness of the human condition.

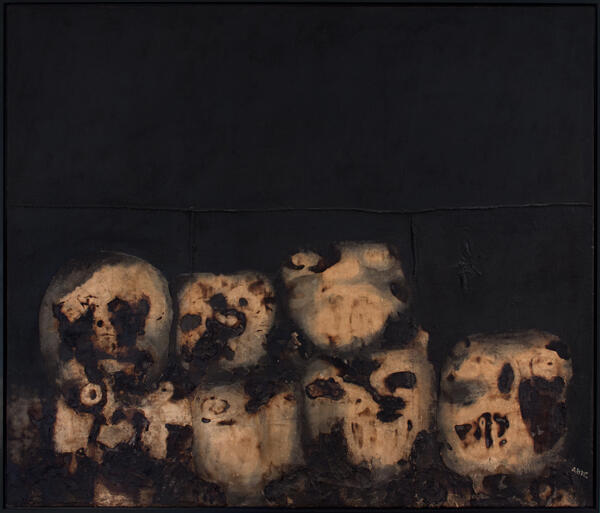

Without denying the intellectual or formal debts with these predecessors, it is necessary to specify that in Eiriz’s tumultuous discourse, concept and blunt communication intercross in an ambiguous strip midway between figuration and abstraction. The result is that she does not only differentiate herself as a leading figure, but she also establishes a refreshing precedent within the circumstances of censure amidst which her work emerges, conquering scholars and disciples for life.

On viewing, for instance, overwhelming works such as Los de arriba y los de abajo (Those above and those below), 1965 or Retrato de familia (Family Portrait), 1994, titles separated by three decades, one may confirm the consistency of an organic legacy that exposes existential panics and pain, always relying on the command of a craft that effectively activates each pictorial resource in the expressive perturbation that the somber images record.

This may explain why the curator decided to include in the project two sections in which she displays a series of works by artists from later generations who attest to the influence and the continuity of the Eiriz myth. The works of Luisa Basnuevo, José Adriano Buergo, Ana Albertina Delgado, Nereida García Ferraz, Ana Mendieta, Glexis Novoa, Sandra Ramos, Gladys Triana and Tomás Sánchez, illustrate Antonia’s decisive influence, especially in the case of Tomás, who is perhaps her closest disciple. All of them evince in some way the singular paths of symbolic expression traveled by the artist who is the subject of this homage, and who was, in turn, forged by the teachings of the group of abstract and expressionist creators called Los Once (1953-1955), particularly by those of Guido Llinás, whom she considered her mentor, a reference that the curator has taken into account.

In the end, the retrospective leaves the impression that it is not possible to understand the course of Cuban art of the past five decades if we ignore the tremor that the irruption of Antonia Eiriz represents. To set aside such visceral relationship between ethics and aesthetics would pose a permanent conflict with art history.