THE RESURRECTION OF THE HERO: THE LAST FACE OF CHE GUEVARA IN FREDDY ALBORTA AND LEANDRO KATZ WORKS

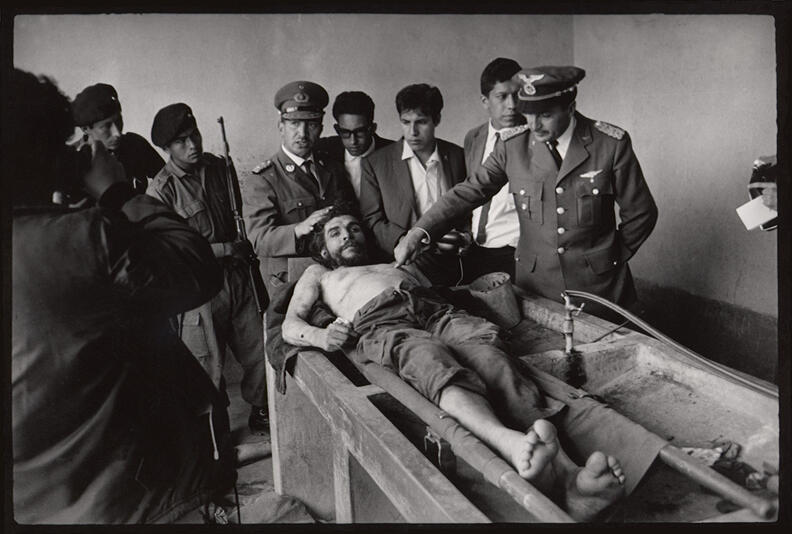

The noted art historian John Berger was the first to notice, in the same year of Che's death, in 1967, when the terrible image of the Bolivian photographer Freddy Alborta was published for the first time, its overwhelming similarity with the dead Christ (1480 -90) of Mantegna and with the lesson of anatomy (1632) of Rembrandt. According to Eduardo Grüner, with "the disappearance of the living body" and with the possibility of imagining Che "beyond death," his image was installed in the collective imagination as a very powerful embodiment of the myth of the revolutionary, full of Affective resonances related to the figure of Christ. Although in the interview that Katz made to the Bolivian photographer, he did not recognize having had in mind the works mentioned by Berger, his impressive press photograph clearly exemplifies the survival and migrations of the images through the reiteration of some of the Affective formulas of which the founder of the critical iconology Aby Warburg speaks to us. Thus, the documentary El día que me quieras (1997) by the Argentine artist Leandro Katz, and the same press photograph of Alborta, despite their different means and creative intentions, can be considered as a new "ghost panel," which is worth worth studying, especially in relation to the pathos of the ideals of the Latin American left, mainly during the 60s and its reworking in the 90s.

1st picture: the death of Che and the staging of lamentation

On October 8, 1967, the Bolivian army, with the support of the CIA, captured Ernesto Guevara alive, in the Quebrada del Churo. Wounded and ill, Che was transferred and held prisoner in a rural school in La Higuera, where the following day he was executed.

Once dead, his body was transferred to Vallegrande. It was said then that Che had died in an armed confrontation and journalists were summoned for a press conference, not only to communicate the news of his death, but to give evidence of the fact and identity of Che.

To do this, the Bolivian government mounted a sinister scenery exhibiting the body of Che as if it were a spectacle and a political ritual in the manner of a scene of Christian lamentation, although surrounding it by its executioners and witnesses called for the occasion, and not for their relatives, in order to show the power of the State and its exemplary way of punishing.

1st picture: the death of Che and the staging of lamentation

On October 8, 1967, the Bolivian army, with the support of the CIA, captured Ernesto Guevara alive, in the Quebrada del Churo. Wounded and ill, Che was transferred and held prisoner in a rural school in La Higuera, where the following day he was executed.

Once dead, his body was transferred to Vallegrande. It was said then that Che had died in an armed confrontation and journalists were summoned for a press conference, not only to communicate the news of his death, but to give evidence of the fact and identity of Che.

To do this, the Bolivian government mounted a sinister scenery exhibiting the body of Che as if it were a spectacle and a political ritual in the manner of a scene of Christian lamentation, although surrounding it by its executioners and witnesses called for the occasion, and not for their relatives, in order to show the power of the State and its exemplary way of punishing.

2nd picture: the photographs of Freddy Alborta and the survival of Christian iconography

However, in spite of the exemplary intentions to produce terror, subjection and humiliation intended by the perpetrators, in the eyes of the world the images of the sinister ritual, taken by Alborta (Figure 1), in the collective imaginary became more like the clear expression of the dehumanization of power at that time, which sought to exemplarily punish an entire generation, of which, as Grüner points out, Che was really only the emerging figure, and not the catalyst.

The violence exerted on the body of Che, exhibited in the most forceful way through the image that went around the world, contributed to the heroic mythification of the revolutionary, because the fact that his life had been cut off so prematurely, the display of his wounded and half-naked body, his beautiful bearded face, and his extraordinary mystical, visionary and profound look, which in spite of death still seemed to keep looking, recovered very present memories in the collective imaginary in relation to the figure of Christ . Thus, the death of Che, represented in the photograph of Alborta as the drama of Christian lamentation, was also read as the symbol par excellence of the final expiatory sacrifice, in this case, of the revolutionary hero.

3rd picture: the desire for the resurrection in the movie The day you love me (1997) by Leandro Katz

Now, while the photo of Alborta is mainly related to the Christian iconography of lamentation, the work of Katz that takes it as a starting point, rather updates the concept of resurrection.

According to Carl Gustav Jung, Jesus as a personification of the messiah is related to the figure of the hero of classical mythology, as one who is able to return from the underworld and conquer death to restructure and fix the society of mortals. Through the sharing of their suffering, death and resurrection, the idea of the risen Christ not only helps us to diminish the anxiety that death causes us and the fear of dying, but it also gives those who participate in the idea a sense of human dignity and the meaning of life renewed. For Jung, the resurrection of the body is an expression of the glory of human transfiguration, as the spiritual potential latent in humanity. In short, it is a metaphor according to which, through ideas and the footprint we leave in our contemporaries, we can continue living.

The documentary film, Katz's The Day You Love Me (1997), is a film investigation that invites us to reflect on the meaning of Che's death, as well as on the power of photography and art, in the construction of the myth of the hero, and especially the concept of the resurrection (Figure 2). Starting from the published image of Alborta, and from a report he made to the photographer (Figure 3), in which he recovered the other shots he had taken at that dramatic moment, Katz uses different creative strategies, mainly fragmentations and approaches, which they allow you to re-photograph the original images recovered in that interview.

The film is also complemented by filming of a traditional folk dance in which the masked dancers represent the confrontation between the forces of evil and those of the good (Figure 4); scenes interspersed with others that recreate a metaphorical ritual of homage to Che that the peasants of the Andean region celebrate each year to commemorate his death (Figure 5). In his film Katz he also uses music: a solo of David Darling's cello and fragments of popular Bolivian music; as well as literary texts: The day you love me, popularized by the song played by Carlos Gardel; The witness, by Jorge Luis Borges, with some variations of the same Katz; and There is no forgetting of Pablo Neruda, read in the poet's own voice. The posters with titles or questions, separate the narration into sections as if they were chapters of a book, providing an element of distancing within the story.

Rightly Grüner interprets the documentary as a tribute to Che, and even to Alborta himself, but mainly to "those flags, and that floral offering, and those diabladas, and those masses that hold the flags and the flowers and the masks rituals. "The same author continues emphasizing how one of the main elements of the documentary is the re-union that Katz achieved between Che, with the other murdered guerrillas, Willy and Chino, who were in the same improvised morgue as Che, but on the floor (Fig. 6), in photos taken on that occasion but kept unpublished, thus extending the homage to so many other fallen and unburied, which by extension also include our disappeared of recent decades. Through this scene, of the inclusion of the Bolivian peasants and, finally, of the very subtle technical resource of the "cast in chains" in which the last image of the plane dissolves while, in overprinting, the first image of the next plane, one has the impression that Che's body is incorporated, that the guerrilla, almost literally, resuscitates, with which Katz recovers both the historical experience and the romantic hope, expressed in the film in Gardel's tango, and in the image of the girl with the offering of roses, that someday the ideals of freedom personified by the myth of Che materialize.

As a final piece

While the scenic montage that gave birth to the two works analyzed here, was created to demonstrate precisely the inexorability of the death of Che, and through him, the very failure of the revolution in Latin America, both the photograph of Alborta, which It recovers the iconographic tradition of Christian lamentation, as, especially, Katz's work, which updates the illusion of the resurrection, tries to deny it, emphasizing instead the idea of the beginning of a new life or of a regeneration, understood in a secular and philosophical sense, as the continuity and vitality of the revolutionary movement.

For Jung, the impotence and the unacceptable of death requires fiction, according to which there is the possibility of another life that is eternal, not perishable and perhaps much more significant than the physical life we know. Katz, using the fiction of the resurrection, dismantles the image-document of Alborta, and mainly the staging mounted by the victimizers of Che, to reorganize the story of the traumatic historical past, and to retell another possible story, according to their own revolutionary and hopeful desires in which Che, as personification of the ideals of freedom, as Eduardo Galeano said, continues and will continue to be, "the most born of all".

-

Fig. 2, Nuestro Sr. De Malta.

Fig. 2, Nuestro Sr. De Malta.