Integration and Resistance in the Global Era: Personal Reflections

In the wake of devastating hurricanes and a faltering local and global economy, the Havana Biennial successfully harnessed the support of Cuban institutions as well as friends, foundations, and governments outside the island. (Illustration #1)

In celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Havana Biennial (it began in 1984), the Biennial outdid itself in notable ways. It was no small accomplishment that some 323 artists in seventeen venues were selected and organized by a curatorial committee of eight full-time curators, sixteen outside curators, thirteen consulting curators, and nineteen assistants. The Biennial catalogue (532 pages), as well as those for the Theoretical Event and the Compilation of Texts, are the most ambitious and thorough documents produced since inception and will undoubtedly serve as inestimable resources for future studies on biennials in general and this one in particular.

Since 1989 the biennials have been organized around broad thematic concerns. This year’s theme, Integration and Resistance in the Global Era, is a concept that occupies the daily thinking, planning, and activities of every kind for billions of people. Artists, individually and collectively, responded through painting, installations, prints, photographs, video, film, and Xeroxes. The work presented proposes, challenges, embraces, and disputes cultural, political, and economic diversity—an admirable, even wondrous achievement. There were spectacular formal projects, such as Chelsea Meets Havana, and others, more anthropological in nature. Twenty-six galleries in New York presented work by artists, and the El maíz es nuestra vida project, conceived by and for women from Mexico, presented installations, videos, performance, a rap group, and a workshop in the community. Both Chelsea and El maíz offered audiences diverse visual and conceptual messages, symbolic of the expansive languages of the art worlds’ many centers and peripheries.

The Biennial continues to give significant presence to Cuban artists, at different stages of their careers, thus introducing outsiders to what may be acknowledged as a lion’s share of extraordinary talent. Below I mention Alexandre Arrechea, Tania Bruguera, Liset Castillo, Carlos Garaicoa, Alexis Leyva Machado (Kcho), and Yoan Capote, among others, whose visually compelling, well-crafted works address concerns in everyday life from the proximity of the front door to a corner around the world.

Arrechea’s installation La habitación de todos (2009) includes a video, drawings, and a sculpture, elements that connected the fluctuations of the Dow Jones Industrial Average to the housing crisis in the United States. (Illustration #2) The video projected footage of the Dow; the drawings featured the houses; the sculpture, constructed on a long table, consisted of a row of metal houses in silhouette on a long metal pole with a chart spanning the length of the sculpture. The chart has lines with numbers from 0 to 100, representing the percentage point changes of the market. At the end of each day, the artist hand-cranked the pole so the houses expanded or contracted according to the Dow’s upward or downward fluctuations. (The artist intends to make a large-scale, automated sculpture based on this model.)

Castillo’s Archaeologies of Power (2009) is a model with 216 modern buildings depicting an urban epicenter with skyscrapers surrounded by residential properties. The title seems to refer to a world-renowned group of architects whose “visionary” buildings have had a visceral impact on millions of citizens. The model, however, also underscores the interests of curators who present an architect’s proposals, in the form of drawings and models, to a larger public before a building’s actual construction. (Consider, for example, recent exhibitions of drawings and models of such Pritzker Architecture Prize recipients as Norman Foster, Herzog & de Meuron, Zaha Hadid, and Renzo Piano, among others.)

Capote’s Open Mind (2006-2008) is a large-scale site-specific installation configured in the image of a brain with its upper part open to reveal a maze of passageways. Conceived as a future public artwork, the spectator views the model (at El Morro Cabaña) from a ramp looking out and down into the sculpture where life-sized figures were placed inside some of the walkways. Aside from its attraction as an installation, as well as its potential as a public artwork, the title, form, and meaning call for an open mind in what might be a redefining period in Cuban political history.

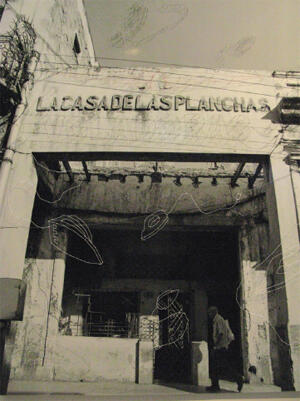

The exhibition of photographs and installations of Carlos Garaicoa at the Museum of Fine Arts was characterized by humor, irony, double meanings, and wordplays. The artist’s photographs of old, decayed, destroyed, or abandoned buildings in Havana are poignant reminders of the contingent nature of everyday life. The House of Cards (2006-2009) illustrates the artist’s modification of a photograph of a store no longer in business. (Illustration #3) The intervention consists of drawing images of irons with pins and thread, thereby investing the dilapidated scene with a sense of the vitality of its former commercial life.

Bruguera’s El susurro de Tatlin #6 was performed in the inner courtyard of the Center Wifredo Lam. The performance space consisted of a platform located in front of a long theater curtain, a podium, a microphone, two young attendants dressed in green fatigues, and a dove that was placed on each speaker’s shoulder. Bruguera stated that she wanted her work to provide a space where people could speak about Cuba’s realities.” In the absence of a formal introduction, the performance came to life when a person from the audience read her one-minute commentary in which she called for unrestricted access to the internet “to write opinions.” Another person went to the podium and exclaimed: “Long live democracy.” Another expressed the hope that the day would come when expressions of liberty would not be part of a performance. Although the majority of persons asked for substantive changes in present policies, some people spoke in favor of them.

Surprised by the forthright nature of the varied responses, I consider Bruguera’s performance successful because it created, for however briefly, a space for divergent voices that presented their views in a civil manner. If subsequent political change occurs, elements of that discourse will ultimately be negotiated outside the Biennial venue. It will be interesting, indeed, to watch the ripple effects of that performatic moment.

Most of the videos and installations were presented at the San Carlos de la Cabaña Fortress, a historic monument overlooking Havana Bay. Punto de encuentro was installed in the dry moat between two massive stone walls outside the entrance to La Cabaña. Kcho, together with a cadre of many artists, musicians, actors, dancers, and art instructors re-created a small, tent city similar to those set up in several places in Cuba after 2008’s devastating hurricanes. They comprised a core of volunteers known as the Brigada Marta Machado, named in honor of the artist’s mother. After toiling all day, everyone gathered in a special tent to participate in artistic activities, hear concerts, and see movies. The evenings of “art” provided great emotional relief for those who had lost everything. At the Biennial, similar artistic events also took place in the Galería: by day the public could see the documentation of the reconstruction work as it progressed; by night, the public heard live concerts.

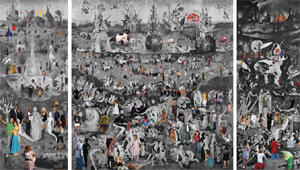

Inside La Cabaña in some six pavilions, many works gave pause for both enjoyment and reflection. A few examples follow. Lluis Barba’s Garden of Delights (Bosco) adapts the imagery from Hieronymus Bosch’s 16th-century painting of the same title. (Illustration #4) The Spanish artist inserted contemporary images of people, places, and objects culled from many sources. The “garden” thus became a nonhierarchical place for interaction among the wealthy and the poor, the institutionalized and the marginalized, the religious and the secular, the famous and the anonymous. New figures in the garden include high-profile art collectors, critics, artists, movie stars, rappers, musicians, and singers. Even Batman makes an appearance along with Buddhist monks, Catholic nuns, malnourished children, and a beggar woman amidst cash machines, soccer balls, and footballs, and iconic images and logos of multinationals such as Coca Cola and Mac Donald’s. References to both local and global production and consumption populate the regions of heaven, earth, and hell as imagined by Bosch and transformed by Barba.

Dan Halter’s Zimbabwe $1 Million (2009) is a bas-relief map of a farming region in Zimbabwe formerly known as "the bread basket" of southern Africa. The map is made from a million shredded Zimbabwe notes, all but worthless currency due to hyperinflation. The work critiques the failed political policies of the former government that in 2000 appropriated white-run farms, thereby creating conditions in which the economy began its downward spiral. Formally, the artist draws on the rich tradition of African textiles, known for their complicated weaving and design. Halter’s delicate yet intricate work recalls the extraordinary art of El Anatsui, the Ghanaian born artist, who uses strips of metal to weave large-scale tapestry-like sculptures in the form of textiles.

In contrast to Halter, Patrick Hamilton’s installation Pails (2005-2009) speaks to the new wealth produced by the banking and finance industries in Santiago, Chile. The series of photographic views (housed in shallow pails) of the new architectural zone is evidence of the boom resulting from the neo-liberal policies of more than twenty years.

Resistance to genetically produced corn is the subject of Eduardo Villanes’s Genética de luz (2009), an installation featuring twenty-nine beadworks, each made from 858 tiny translucent glass beads of different shades of red, blue, yellow, and green arranged in patterns that represent the bonding of four nucleotides in a specific gene sequence in naturally grown corn, Zea mays. One of the beadworks was projected on the wall; the others were exhibited in a light table together with an enlarged printout of a page from an online DNA database maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). (Illustration #5) The NCBI page provides the name of the specific organism, Zea mays (corn or maize); the sequence of the 1,561 nucleotides of a gene (a fragment being atggcggtgtg); the names of authors of the article “DNA constructs and methods to enhance the production of commercially viable transgenic plants”; the patent number and the date, and the name of Monsanto Laboratory LLC (US). Villanes included the NCBI page so that viewers could become informed of the attempts of biotech companies to penetrate traditional markets with transgenic corn. If successful, the millennium-long tradition of farming natural corn in the Americas will be altered. (Appropriate to this context, El maíz es nuestra vida was an exhibition in which Mexican artists protested the introduction of transgenic corn in Mexico.)

Many artists explored globalization as a subject in diverse formal, conceptual, and semantic modes. I mention Dario Escobar’s (Guatemala) and Sue Williamson’s (South Africa) works. Escobar’s Kukukam (2009), made of strips of bicycle tires, formed a large, organic, soft sculpture that seemed to emphasize the world’s dependency on rubber for all modes of transportation. (Illustration #6). *Williamson’s work at the Center Wifredo Lam, showed a series of photographs, What about El Max (2005), documenting the sentiments of villagers in a small fishing community in Alexandria, Egypt that is threatened by the military as well as by pollution from a nearby petrochemical company. When interviewing the residents, the artist learned that they preferred to remain in their community rather than relocate, even if their collective livelihood was at risk. In conversations with them, Williamson suggested they inform the world of their plight which subsequently appeared as messages of resistance in Arabic and English on the facades of their houses: “We are like fish—we cannot live away from the sea.”

In the shifting frames of moving images, Claudia Aravena (Chile) and Ananke Asseff (Agentina) produced works that explore emotions of fear. In Aravena’s video Fear (2007), the artist portrays herself, in different face and head coverings worn by many Muslim woman, murmuring the word, fear. Similar images of the artist are juxtaposed against classic scenes from Alfred Hichcock’s movie The Birds. Aravena’s narration attempts to illustrate the ways images and language form negative responses of the “other.”

Asseff’s photographs and video, Potencial (2005-2007), portrays Argentineans armed with guns in the privacy of their homes. (Illustration #7) Judging from the worried facial expressions, the subjects project states of anxiety over fears of being robbed and needing to defend themselves.

On the Road: Northern Exposure (2008) is a video narrative based on a trip Yong Soon Min took to North Korea in 1998 with two academic colleagues and their North Koreans minders. (Illustration #8) Ten years later Min decided to edit footage taken on a day when the group traveled between Pyongyang and the DMZ (demilitarized zone). She was inspired to create a visual narrative by Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, his seminal Beat novel that took ten years to complete. She saw his experiences as a metaphor of her own struggles to recall the blurred images of places and people in a country that is now all but inaccessible to outsiders. Min’s video makes some use of slow motion to sustain moments of fleeting places and to provide “a sense of [the] intimacy and connection,” that was never realized.

At the beginning of the video, Min’s voiceover recites stanzas from T.S. Eliot’s poem “Ash Wednesday” that acknowledge the impossibility of holding on to place and time: “Because I know that time is always time / And place is always and only place / And what is actual is actual for one time / And only for one place.” In ending, Min poses unanswered questions regarding her trip to North Korea, which, she states, is burdened by too much cold war history. In retrospect, the artist realizes “that even then, that place and time did not seem its own.”

On a less philosophical note, Chen, Xiaoyun (China) created a very humorous four-minute video, Love You Big Boss (2008). (Illustration #9) He directed an ersatz group of people, who played the beginning stanzas of The Star Spangled Banner in tune before going off into an improvisational jam session out of tune. The resulting disharmony seems to reflect a cacophonous spirit of China in change. Who is Big Boss, anyway, in this shifting world power scenario? You decide.

In ending this article, I mention Cai, Guo-Qiang (Chinese), *Luis Camnitzer (Uruguay, based in the U.S.), Máximo Corvalán (Chile), *Guillermo Goméz Peña (Mexico, based in the U.S.), *León Ferrari (Argentina), and *Antonio Martorell (Puerto Rico). These diverse works appeal for different sensorial or cerebral reasons. During Cai’s spectacular outdoor performance in Plaza San Francisco, he ignited a boat with gunpowder, mesmerizing hundreds with the ephemeral effects of the explosives.

Goméz Peña’s performance, Corpo Ilicito, was also received with great enthusiasm. The multidisciplinary artist spoke in tongues, interweaving English, Spanish, and imaginatively inventive words as he conjured a critical, parodic discourse on inter- and intra-border issues loaded with a range of humanitarian issues. The artist’s work, consistent with many others in the Biennial, affirms art as a necessary experience within the political and cultural definitions of society.

Camnitzer’s Last Words (2006-2008), part of a larger exhibition at the Center Wifredo Lam, consisted of seven letters found on the web. The letters contain the last words written by prisoners shortly before their executions in Texas and express their heartfelt love for their families. It was somewhat surprising to read the condemned prisoners’ sentiments, accustomed as we are to the emotional outpourings of the victims’ families.

Corvalán’s installation at the Morro Cabaña combines painting, sculpture, and neon signs. The title, Free Trade Ensambladura (2005-2009), references a series of free-trade agreements with Latin America, Europe, Asia, and the United States resulting in global partnerships that have expanded Chile’s economic bases. (Illustration #10) The painting features the Atacama Desert, a major region of copper mining; the sculpture features reproductions of Atacamenian mummies. The neon signs inserted in the mummies exclaim: “WELCOME,” “DE PASO (Passing By),” “OPEN.” The words add layers of elusive meaning to the disconcerting images of the mummies, providing moments for reflection on Chile’s recent sociopolitical shifts.

León Ferrari: Agitador de Formas at the Casa de las Américas was a kind of mini-retrospective demonstrating the visual, material, conceptual, and critical power of this multifaceted creator. Planeta is a globe covered with toy cockroaches. The bugs, each with a small flag attached to its body, cross the lands and seas in formation. Where is the resistance to this invasion? There doesn’t seem to be any!

With death as his muse, Martorell created La Plena inmortal (2007), an exhibition of woodblocks with images appropriated from historical masters and transformed by inserting the image of a skeleton as subject of the portrait. (Illustration #11) With characteristic humor and matter-of-factness, Martorell wrote: “Immortal Plena, because death sings and invites us to dance, and because we mortals swing to the song she plays, whenever she wants to play it, she, Plena, death herself, is immortal. Meanwhile, we mortals, face the music and dance.

Work from Martorell’s series, together with woodcuts, linotypes, and potato prints made by local people of all ages, was installed throughout the Plaza de la Catedral on the last day of the inaugural week of the Biennial. During that joyous event, hundreds danced the plena in the public square where art and life were integrated. It seems appropriate to end on this celebratory note.

...............................................................

1. Rubén del Valle Lantarón, director of the Biennial, wrote: “The term has become one of the most appealed to for the analysis of the phenomena of the contemporary world, whether of domestic, ecologic, technologic, scientific, political or cultural nature. It is a new era where conflicts excel the already traditional North-South, East-West, Capitalism-Socialism poles to become issues that involve the whole planet to an equal extent and where the survival of the human species is at stake in many cases.” Décima Bienal Habana: Integration and Resistance in the Global Era. Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam. Consejo Nacional de las Artes Plásticas (2009), p. 19.

2. See http://www.cubaencuentro.com/es/entrevistas/articulos/nadie-esta-dispuesto-al-borron-y-cuenta-nueva-171188

3. Rubén Del Valle, email communication with the author, May 12, 2009.

4. This site-specific encampment had a dramatic visual appeal similar to that of Kaarina Kaikkonen’s Departure (2003), an installation of 1,500 jackets furling in the wind, forming the outline of a large boat also located in the same place in the dry moat.

5. Very recently the new unity government started to allow foreign currency to be used instead of Zimbabwe dollars.

6. An asterisk before an artist’s name indicates that they were “a specially invited artist.”

7. Aravena’s father is Chilean and her mother Palestinian. Much of the artist’s work deals with transcultural issues.

8. The artist was part of the exhibition Punto de encuentro organized by Kcho at the Convento de San Francisco (see note 2 above).

9. Goméz Peña invited Tania Bruguera to collaborate by creating two different performances that were supposed to take place simultaneously in separate, but nearby, patios on the first floor of the Center Wifredo Lam. For reasons unknown to me, the audience remained in place during the Bruguera performance and then moved on to participate in Goméz Peña’s. He refers to his cast as “chicubanaria” in acknowledgment of their Cuban, Chicano, Canary Islands, and Spanish backgrounds. See “Goméz Peña explica su posición frente a la ‘Controversia’ Tania Bruguera,” written from Mexico City on April 13. I received it from the Center Wifredo Lam on April 24, 2009.

10. The plena is a popular song and dance composition originally from Puerto Rico; it serves as a narrative for events as diverse as politics, sports, crime, and natural disasters.

-

1. Integration and Resistance in the Global Era. 10th Havana Biennial. San Carlos de la Cabaña Fortress / Photo Julia P. Herzberg. Integración y Resistencia en la

1. Integration and Resistance in the Global Era. 10th Havana Biennial. San Carlos de la Cabaña Fortress / Photo Julia P. Herzberg. Integración y Resistencia en la

Era Global. X Bienal de La Habana. Fortaleza de San Carlos de la Cabaña / Fotografía Julia P. Herzberg. -

Alexandre Arrechea, La habitación de todos (detail / detalle), 2009. Installation: stainless steel, table, drawing; sculpture 118 x 7.87 x 11.81 in. Instalación: acero inoxidable, mesa, dibujo, escultura, 30 x 300 x 20 cm. Courtesy artist and Magnan Projects, New York / Cortesía del artista y Magnan Projects, Nueva York.

Alexandre Arrechea, La habitación de todos (detail / detalle), 2009. Installation: stainless steel, table, drawing; sculpture 118 x 7.87 x 11.81 in. Instalación: acero inoxidable, mesa, dibujo, escultura, 30 x 300 x 20 cm. Courtesy artist and Magnan Projects, New York / Cortesía del artista y Magnan Projects, Nueva York. -

Lluis Barba, Garden of Delights (Bosch), series Tourists in Art / Jardín de las delicias (Bosco), de la serie Turistas en el arte, 2007. C-print on aluminum. Edition

Lluis Barba, Garden of Delights (Bosch), series Tourists in Art / Jardín de las delicias (Bosco), de la serie Turistas en el arte, 2007. C-print on aluminum. Edition

6; 212.6 x 118 in. / Impresión diasec Grieguer. Edición 6; 540 x 300 cm. Courtesy / Cortesía Jacob Karpio Galería, Costa Rica. -

Carlos Garaicoa, The House of Irons, from the series Untitled (Phrases) / La Casa de las planchas, de la serie Sin título (Frases) 2006-2009.

Carlos Garaicoa, The House of Irons, from the series Untitled (Phrases) / La Casa de las planchas, de la serie Sin título (Frases) 2006-2009.

Digital photograph laminated on Gator Board, pins, thread. Fotografía digital laminada en Gator Board, alfileres, hilos; 151,8 x 121,8 cm. Courtesy artist / Cortesía del artista.