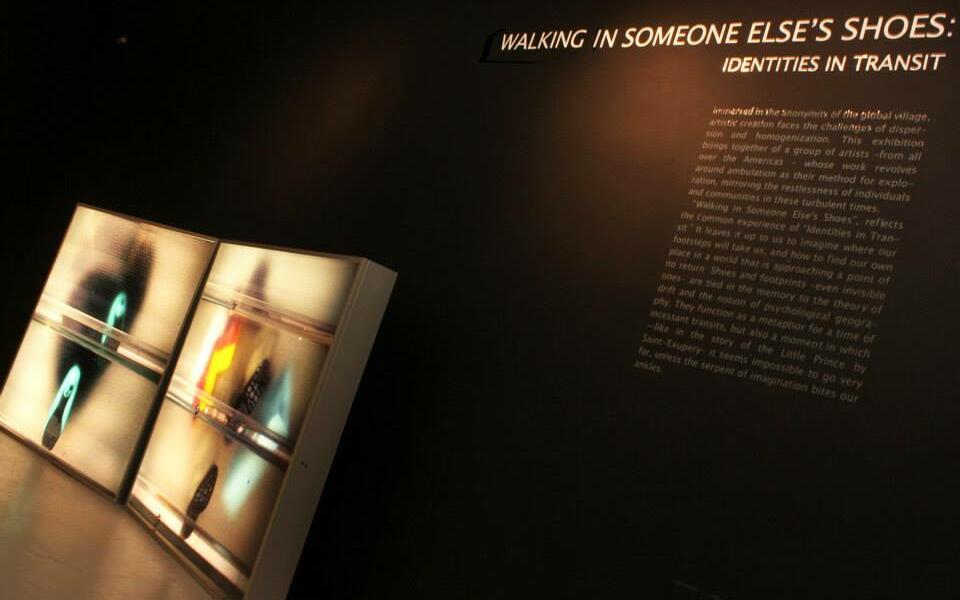

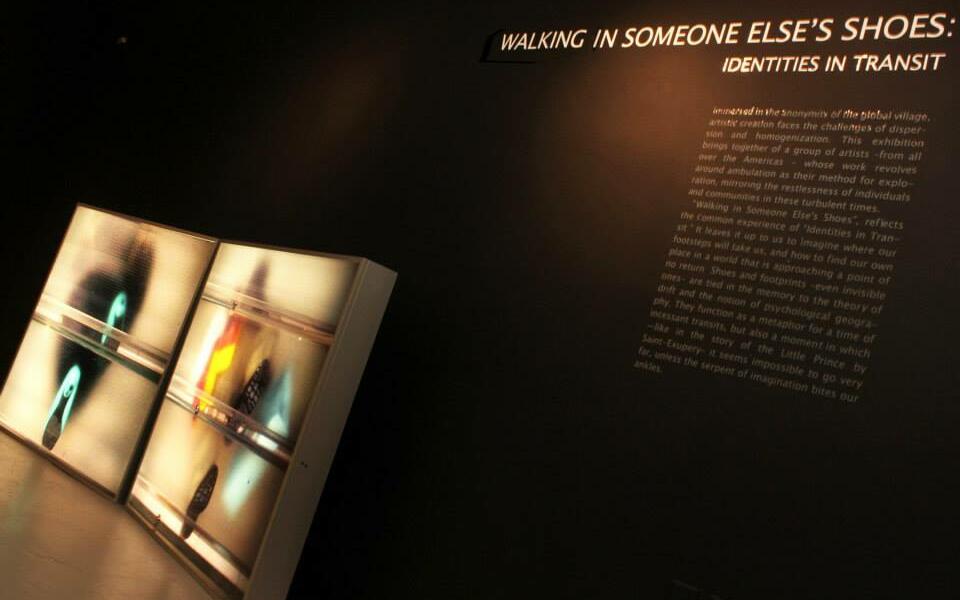

23 Hispano American artists in “Walking in Someone Else’s Shoes” in AAF, Miami

The exhibition “Walking in Someone Else’s shoes (Identities in Transit)” at Aluna Art Foundation in Miami, gathers together a group of contemporary works that revolve around the transhumance as a method, and that reflect the restless landscape of individuals and communities who walk in turbulent times.

Many works include the concrete representation of the shoe and a poetry of it which is linked to individual transit, to intimate forms of memory, and last but not least to the course of collective history, including the migration routes, and the traces of exodus or a psycho-geographic vision of the scenery of disappearances.

The exhibition shows crossing of paths that in a certain way depart from all the Americas, given the fact that the majority of the works have been created by artists from different generations and cities, from Buenos Aires to New York. Nevertheless, their vision crosses the local to cover the global transits of a time of uncertainty, where a new form of nomadism is extended.

The participant artists are Graciela Sacco (Argentina), Patricio Reig (Argentina/España), Marina Font (Argentina/USA), Roberto Huarcaya (Peru), Cecilia Paredes (Peru/USA), Luis F. Peláez (Colombia), Linda Pongutá (Colombia), Luis Roldán (Colombia/USA), Manuel Zapata (Colombia/USA), Andrés Michelena (Venezuela/USA), Felipe Ehrenberg (México/Brazil), Mario Bellatín (Peru/ Mexico), Regina José Galindo (Guatemala), Ronald Morán (Salvador), Walterio Iraheta (Salvador), Antuan (Cuba/USA), Humberto Castro (Cuba/USA), Willy Castellanos (Cuba/USA), Gustavo Gavilondo (Cuba/USA), Hugo Moro (Cuba/USA), Debra Holt (USA), Patricia Schnall Gutiérrez (USA), Alexandra Rowley (USA), y Xavier G-Solis (Spain).

The curatorial proposal was developed by Aluna Curatorial Collective (Adriana Herrera & Willy Castellanos) to accompany the works with precise personal texts: each artist narrates the stories of the represented transits. As a playful and pedagogic element the exhibition includes various shoeboxes that contain theoretical references ranging from the meaning that walking had for the Aristotelians and Peripatetic, to fragments Guy Debord’s situationist Drift Manifesto, or the reflections of Michael de Certau on the privilege of walking. Similarly, the spectators will find a wall with references to famous art works that allude to the act of walking and to the shoes as a metonymic object.

The “walking” begins with the photographs of the spectators that journey through the installations of labyrinths quasi invisible of Ronald Morán, a very recent series that refers to the situations of uncertainty of a drifting humanity, culminating with a video of Regina José Galindo’s performance where she incarnates a contemporary vision of Ariadna’s cord which confronts us with continental violence.

In the first room, a kind of constructed map extends atop the floor with residual floating papers found by Luis Roldán in his walks around his study in New York, surrounded by an installation and a video of the series Metro2 of Gaciela Sacco, emerging from the question about the minimum space the human body needs and the research on the tension between the inside and outside that generates the movement and the same history of our own walk. Luis F. Peláez’s sculptures with bags that contain the very same paths activate the poetic memory of displacements and of the horizons that are subsequently left behind to become a remembrance or a desire evoked in the midst of transit.

A section of the exhibition explores the relationship between the steps and the historical memory. A piece by Morán captures the fleeting traces of the same spectators in the installation where he reconstructed with nylon threads the cell bars of an old prison in Tegucigalpa, abandoned shortly after the decaying overcrowding in the cells –very common in Central America— and a furious hurricane turned it into a graveyard for dozens of prisoners. Analogously, a beautiful installation with used white shoes of Walterio Iraheta forms a sort of ‘mandala’, a sacred figure that evokes and at the same time exorcizes the violence experimented by the inhabitants of San Salvador. The Andean “Mercurio” that Cecilia Paredes represents in the photograph of a pair of dilapidated shoes with ripped wings recreates the mythology of quotidian life in the poor populations of a continent where messengers have travelled a long way without getting anywhere.

The series of photographs of the wrecked and reconstructed ‘tenis’ shoes of street basketball players in Habana documents part of the neighbourhood life of Gustavo Gavilondo, who’s own player shoes form part of his work, and his participation in acts of playful and collective expression which, among other things, allowed to gather shoes for the players reached by the act of necessity.

A documental image by Willy Castellanos registers the instant in which a raftsman, the anonymous protagonist of the Cuban Exodus of 1994, hands over his sandals as he boards the raft, and projects it in the wall as a shadow of a vanishing history. Meanwhile the limits of the interpretation of the scene are exposed in the accompanying text, the gesture inserts in an archive that reconstructs the history of the world and the relationship between memory and power since the times of Tutankhamen until the present, with images of shoes taken from the internet and available for spectators to arrange them as they wish.

Felipe Ehrenberg, pioneer of Conceptualism in Latin America, digitally manipulates the photograph of his own shoes at the edge of a balcony next to the self-portrait in which he walks with the power of a fantastic rope walker that moves along the tight rope above the oscillations of the mercantile world of the present.

Other works evoke the tension between presence-absence that, more than any other dressing piece, can reflect used shoes, capable of conserving the footprint of whomever walked in them. Linda Pongutá does a formal quest about the footprint of a shoe as an object on a material; Hugo Moro draws the shoe that Rimbaud must have lost many times, as an allusion, but also as an homage, to the disdain before the world of the poet that changed language before loosing voluntarily his own trace. Roberto Huarcaya photographs a history of life in the elegant women shoes he found in the garbage in Paris; Marina Font presents a triptych with blue shows evocative of her childhood in Argentina; Patricio Reig a constructed girl shoe –in the way of layers of memory- with the combination of a photograph printed in glass and his own shadow upon the record of old papers. Alexandra Rowley presents the photographs that she made in her studio, after her father’s death, not only of his used shoes but of the footprints formed by the dust they would leave on the floor.

Antuan’s installation with shoes where drying and greening soil grows evokes the construction of a personal destiny by the way of walking. Manuel Zapata captures the red shoes of a little red riding hood in New York followed by the fierce city. Xavier G-Solis prepare a public intervention of sandals that will float above an aquifer zone within the city. The performance by Andrés Michelena changes the gesture of the washing the feet to the disciples for that of preparing the spectators for a proposed walk as a self-finding path.

Other works follow the trace of the feet: in a video of Schnall-Gutiérrez the walk to get home occurs in dreams, and we can only see her naked feet moving through the sheets while she sleeps. Other installations by her of feminine figures without feet evoke the imposed limitations to her walk during centuries.

Debra Hold photographs the feet of a man from Andes that has walked so many miles to the point where they seem infinite; Castro presents a video that evokes his own migrant steps and those of all the exiled in the Caribbean as they cross changing landscapes with metaphoric naked feet. This record of the walking of migrants is evoked with an intense poetry in the video by Morán, recorded from the air, without the trace of human footprints: it shows only the earth, the water and the sky, and the long path where the history of those that search another life is inscribed –and who sometimes find death- while they travel from the south to the north of the continent.

This exhibition reflects a shared experience of ‘identities in transit’ and demands from us that we imagine where will our steps take us and how can we find a place in the world that approximates to the point of no return. Shoes and footprints –even the invisible— function as a metonymic of an epoch of constant transits of which –as in the story of the Little Prince conceived by Saint-Exupéry— it does not seem possible to reach very far, until the serpent of imagination bites our ankles.

-

''Migrantes”; form The Series “ M2”, 2007

''Migrantes”; form The Series “ M2”, 2007

1mx1m - 2 Lightboxes with Backlight (Lamba Prints) - Courtesy: Diana Lowenstein Gallery and the artist - Artist Proof

-

On the left: "Found". From the exhumations - From the Series “My Feet are My Wings” - 12 + 3 Gelatin Silver Print

On the left: "Found". From the exhumations - From the Series “My Feet are My Wings” - 12 + 3 Gelatin Silver Print

On the right: Untitled. From the Series “Mis pies son mis alas – My Feet are My Wings” - 21 pairs of collected white shoes

(Fragment from the original installation of 70 shoes ).

-

Al frente. Cecilia Paredes, " Mercurio", 2013.

Al frente. Cecilia Paredes, " Mercurio", 2013.

En el medio: Willy Castellanos. Inserción, 2013.

Al fondo: Roberto Huarcaya.

Zapatos Mujer, 1998

From the Series Objects Paris