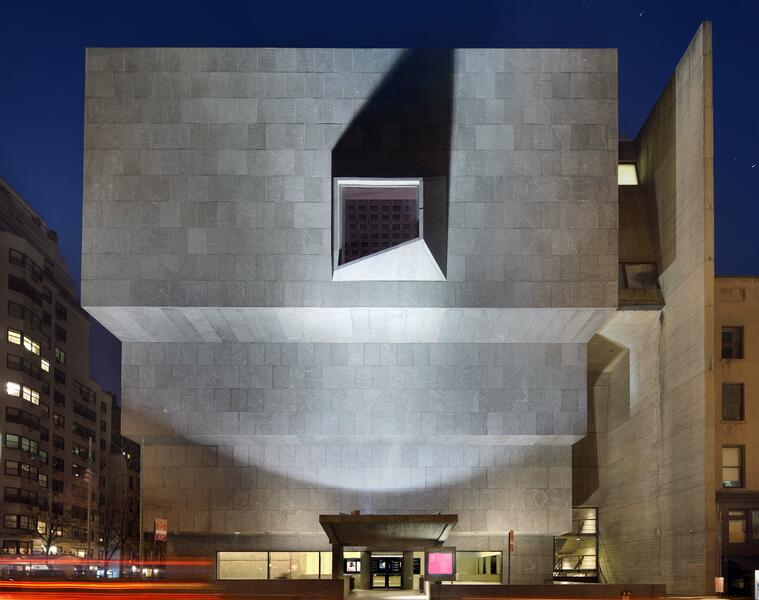

The Met Breuer. New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art inaugurated The Met Breuer on Madison Avenue at East 75 Street in March.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, a preeminent museum in one of the most multicultural cities in the world, inaugurated The Met Breuer on Madison Avenue at East 75 Street in March. The press preview took place on March 1, followed by two weeks of special viewings for Met members. The official public inauguration was on March 18 and, that evening, the Statue of Liberty was bathed in red light, marking the moment. For millions of people in New York City and around the world, the Met Breuer will undoubtedly be a special place to visit.

As a long-time member of The Met, I will share some views on those exciting weeks. On March 1, Museum Director Thomas Campbell welcomed the press, proclaiming, “It’s a great moment!” Those words expressed a palpable sense of excitement. Indeed, a new moment in time and place had arrived. Campbell announced the objective of creating a new, expansive chapter in the Met’s 145-year history by focusing on modern and contemporary art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, within the historical contexts of global art. He discussed the importance of the renovations of the 1966 modernist Marcel Breuer building, originally commissioned for the Whitney Museum of American Art. Henceforth, the iconic granite landmark, named in honor of its architect, will present performances, special events, films, dance and educational initiatives in an intimate space to encourage new ways of understanding the present as it relates to the past, and vice versa.

For several years Sheena Wagstaff, the director of the Museum’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, worked with ten Met curators in preparation for the inauguration. For at least the next eight years, The Met Breuer will present a series of temporary thematic and monographic exhibitions.

The two inaugural exhibitions, Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible and Nasreen Mohamedi, present historical, modern and contemporary art. Relation: A Performance Residency by Vijay Iyer features a series of continuous musical performances and sound pieces, in the Lobby Gallery, by the musician, composer, MacArthur Fellow and Harvard professor who is The Met’s 2015-16 performance artist-in-residence. Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible presents 190 works dating from the Renaissance to the present. It is a cross-departmental curatorial project that proposes varying ideas on unfinished or incomplete works of art.

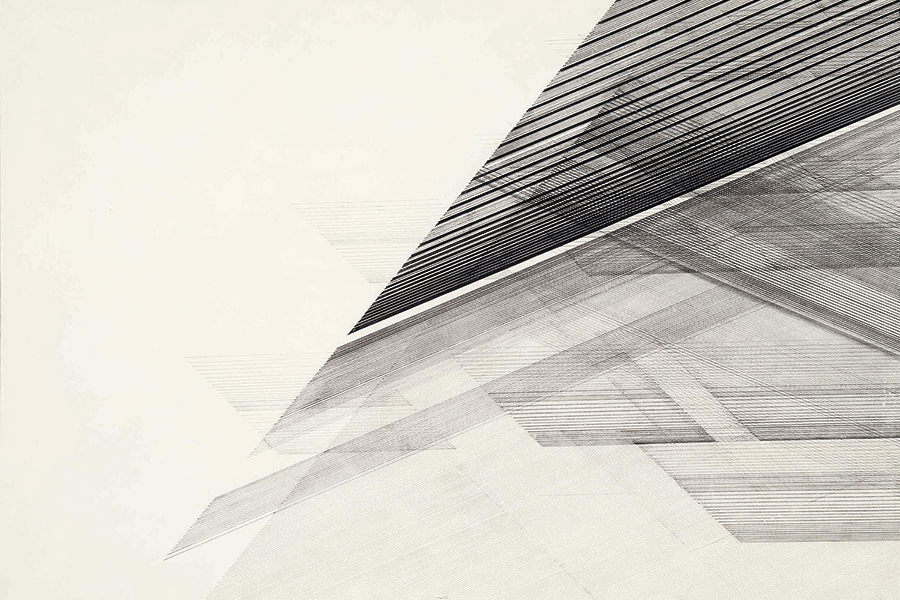

Nasreen Mohamedi, on the second floor, was organized by the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid and The Met, in collaboration with the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi. It is the first United States retrospective of the Indian artist, whose singular aesthetic approach to abstraction positions her as one of the most significant artists of her generation in post-independence India.

Mohamedi was born in Mumbai (formerly Bombay) in 1937, studied in London at St. Martins School (1954-1957), spent a brief time in Bahrain, and then returned to Bombay in 1959 and joined the Bhulabhai Desai Memorial Institute, working alongside the master painters M.F. Husain and V.S. Gaitonde. In 1961-1963, she studied printmaking in Paris and, in 1972, settled in the northwest Indian town of Baroda, where she taught until 1988. She died in 1990 from a neurological disorder.

Mohamedi’s extraordinary work includes drawings on paper, a few paintings and collages, photographs, dairies and notebooks. Preferring drawing over painting, her early work in both mediums reveals her abstractions from nature. As the groupings of her work show—most of which are not titled, signed or dated—she adopted forms of linear geometric abstraction around 1960. With pencil, ink and watercolor on paper, she created intricate linear patterns notable for the varied thickness of the lines, gradations of tone and extreme angles suggesting movement and depth on planar surfaces. Roobina Karode a former student of Mohamedi and curator of the Kiran Nadar Museum, gave a tour, in which she shared how Mohamedi told her students to pull out a strand of hair and then draw it.

Much of Mohamedi’s work is characterized by minimalist compositions. Her later reductive, grid-like forms are characterized by extremely thin, delicate lines. Working against the dominant mode of figuration, she was inspired by such abstract painters as Paul Klee, Malevich, M.F. Husain and V.S. Gaitonde, modern and ancient architecture, calligraphy, Indian classical music and poetry. She was also drawn to Sufism and Zen Buddhism.

Mohamedi began taking photographs at her family’s home in Bahrain, where her father and brothers had an electronics business, which included photographic equipment of the 1960s. Her black-and-white photographs, never conceived for public viewing or exhibited in her lifetime, address the solitude and peace she found in the dessert city of Bahrain and Rajasthan in India, and other places she traveled. She captured geometric structures of dry water towers, the expansiveness of the dessert, road signs, looms and telegraphic poles. During visits to her family’s beach house in Kihim, not far from Bombay, Mohamedi captured the lines, shadows and textures of the undulating lines of sand and ripples of water. To achieve greater abstract imagery, she often tilted the camera to create skewed perspectives.

Her dairies and small notebooks functioned as a place to work, think, write and record her observations and feelings. After writing on lined papers with a felt-tip pen, she covered many of the lines with washes of ink, leaving some lines visible. One of many examples is, A DAY OF THINKING BEGINS. The dairies, never shown in her lifetime, are a kind of beautiful visual poetry. I first saw them at the 2007 documenta installed next to Agnes Martin’s work.

This outstanding exhibition provides a new entry to the developments of modernism across the globe, enabling us to embrace less familiar ideas of people, time and cultures. It reestablishes what we have come to know: centers and peripheries are forever changing and evolving.

Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible is a dense, scholarly exhibition on the third and fourth floors. Wall texts guide the viewer through a series of questions on the states of an unfinished or incomplete work of art. A key question throughout is, When is a work of art complete?

Artists are grouped under subtexts. For example, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Titian’s works were considered, in their time, from the perspectives of non finito or “not finished,” an aesthetic defined by its fluidity and flux. Rubens, Velasquez and Rembrandt’s definitions of the term varied, but Rembrandt is quoted as having believed that “a work is complete if the masters’ intentions have been realized.” That definition, open to many interpretations, includes many artists who created portraits. In the Portrait Mariana de Silva Y Sarmiento, Duquesa de Huescar (1740-1784), Anton Raphael Mengs deliberately left the sitter’s face blank. Pablo Picasso’s Painter and His Model (1914) is a work in progress. Or, as the accompanying text asks, Could it have been a work whose irresolution was deliberate? Alice Neel’s James Hunter Black Draftee (1965) poses a different dilemma. The sitter never returned after his first sitting because he had been drafted for the Vietnam War. Neel declared the painting complete by signing it on the back.

In Camille Corot’s Boatmen among the Reeds (c. 1865), critics noted that since nothing was finished, it would be better to not look too closely. Cezanne’s An Unfinished Conversation explores the question of worth. Many of Cezanne’s pictures were unfinished when shown at his memorial exhibition but, as pointed out, such works were viewed as worthy of both study and acquisition. Artists as different as Picasso and Luc Tuymans have been intrigued by the same questions unfinished works posed.

Artworks on the fourth floor show the many turns definitions of incompleteness or unfinished took in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries according to the artist, place and period. Giacomette never considered his portraits finished. Nor did Barnett Newman. James Kerry Marshall’s Untitled (2009) features an unfinished self-portrait as a paint-by-numbers composition, leaving the viewer to complete the picture. Elizabeth Payton painted Napoleon (After Louis David, Le General Bonaparte vers 1797) in 2015, adopting the unfinished late-eighteenth century portrait of Napoleon, and then declared her painting finished.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991) confronts decline as addressed in the text on Decay, Dwindle, Decline. Installed in a corner, the pile of candy functions as an unconventional portrait of the artist’s partner, who died that year. As viewers remove the candy, the pile slowly disappears until refilled. The work is always in a state of process.

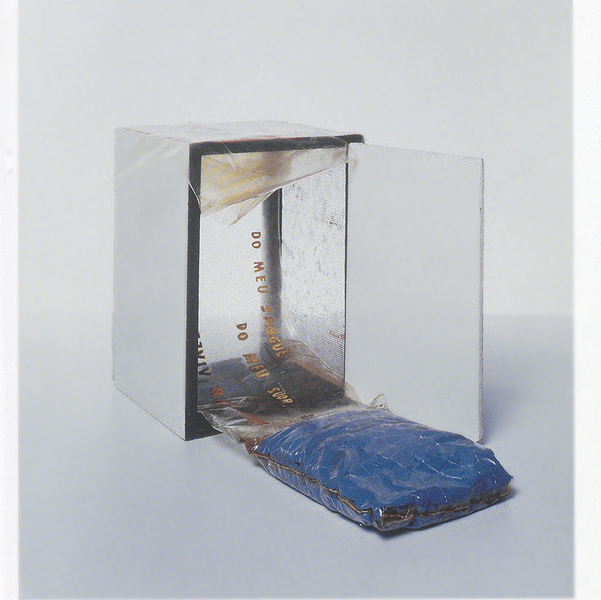

Helio Oiticica’s B30 Box Bólide 17 – variation of Box Bólide 1 (poem box) (1965-66) was conceived as “situations to be lived,” none of which was completed. He inserted various materials in boxes that viewers were originally invited to touch, thus creating an interactive relationship with the work. Lygia Clark’s Bicho/Pan-Cubism Pq (Version II) (1960-63), a sculpture with hinged, movable parts, was intended to be folded by the viewer, who then finishes the work.

The Met Breuer will undoubtedly be a “must see” as is The Met on Fifth Avenue. The new foci on modern and contemporary art from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries will succeed—because art, in a global presentation, matters.

-

Nasreen Mohamedi (Indian, 1937-1990), Untitled, ca. 1975 Ink and graphite on paper. 50.8 x 71.1 cm. Frame: 78.1 x 97.8 cm. Sikander and Hydari Collection

Nasreen Mohamedi (Indian, 1937-1990), Untitled, ca. 1975 Ink and graphite on paper. 50.8 x 71.1 cm. Frame: 78.1 x 97.8 cm. Sikander and Hydari Collection -

Nasreen Mohamedi (Indian, 1937-1990), Untitled, ca. 1970. Gelatin silver print. 22.8 x 34.2 cm. Frame: 43.8 x 50.2 cm. Chatterjee & Lal

Nasreen Mohamedi (Indian, 1937-1990), Untitled, ca. 1970. Gelatin silver print. 22.8 x 34.2 cm. Frame: 43.8 x 50.2 cm. Chatterjee & Lal

-

Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn), The Great Jewish Bride, 1635. Etching; second state of five sheet: 21.8 x 16.4 cm. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929

Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn), The Great Jewish Bride, 1635. Etching; second state of five sheet: 21.8 x 16.4 cm. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 -

James Kerry Marshall, Untitled, 2009. Acrylic on PVC panel, 155.3 x 185.1 x 9.8 cm. Yale University Art. © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

James Kerry Marshall, Untitled, 2009. Acrylic on PVC panel, 155.3 x 185.1 x 9.8 cm. Yale University Art. © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York -

Hélio Oiticica, B30 Box Bólide 17 – variation of Box Bólide 1 (poem box),1965–1966. Oil with polyvinyl acetate emulsion on wood, polyvinyl chloride plastic sheeting, pigment, paper, glass, steel-wire mesh. 32 × 23 × 21.5 cm. Private Collection, London. ©Projeto Hélio Oiticica

Hélio Oiticica, B30 Box Bólide 17 – variation of Box Bólide 1 (poem box),1965–1966. Oil with polyvinyl acetate emulsion on wood, polyvinyl chloride plastic sheeting, pigment, paper, glass, steel-wire mesh. 32 × 23 × 21.5 cm. Private Collection, London. ©Projeto Hélio Oiticica -

Lygia Clark, Bicho/Pan-Cubism Pq (Version II), 1960–1963. Aluminium. 32 × 30 × 30 cm, 1 kg. Collection Daniel Wust, Paris. Courtesy Rachel Adler Advisory. ©Lygia Clark. Courtesy of “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association, Sao Paulo

Lygia Clark, Bicho/Pan-Cubism Pq (Version II), 1960–1963. Aluminium. 32 × 30 × 30 cm, 1 kg. Collection Daniel Wust, Paris. Courtesy Rachel Adler Advisory. ©Lygia Clark. Courtesy of “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association, Sao Paulo -

Met Breuer on March 18, 2016. Front photography by Ed Lederman

Met Breuer on March 18, 2016. Front photography by Ed Lederman